Meeting of the

Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee

Date: 6 July 2022

Time: 11.30am

|

Venue:

|

Council

Chamber

Hawke's

Bay Regional Council

159

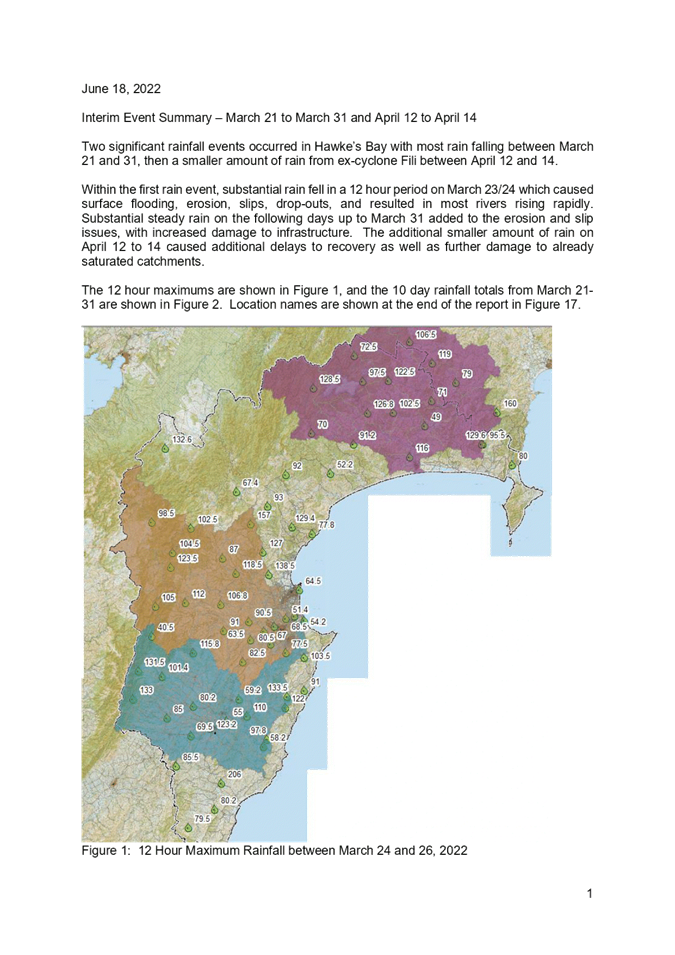

Dalton Street

NAPIER

|

Agenda

Item Title Page

1. Welcome/Karakia/Apologies

2. Conflict

of Interest Declarations

3. Confirmation of Minutes of

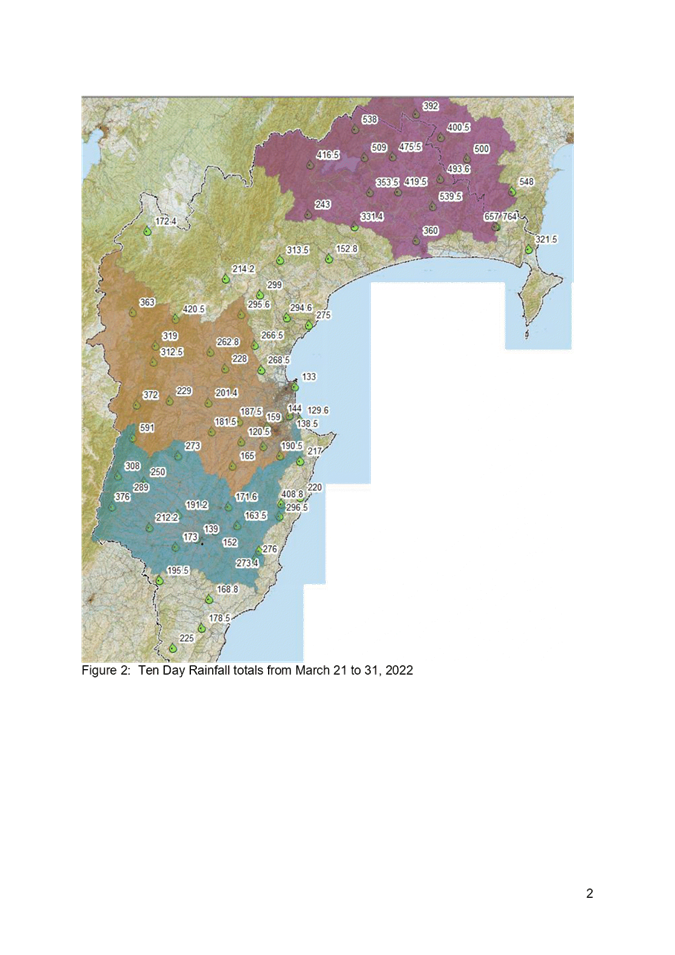

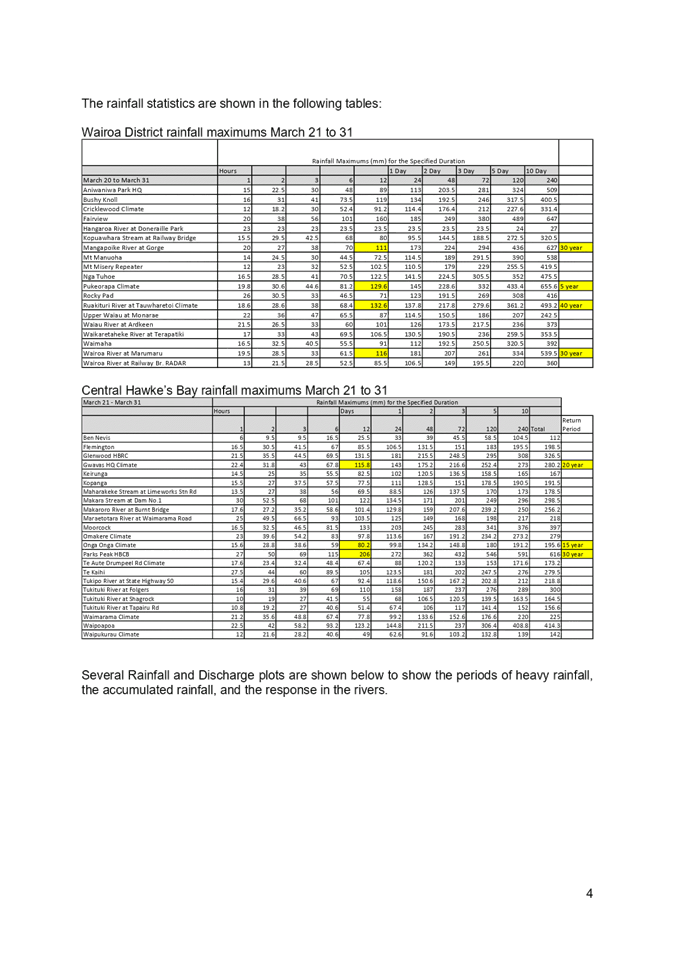

the Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee meeting held on 11 May 2022

4. Follow-ups

from previous Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee meetings 3

5. Call

for Minor Items Not on the Agenda 7

Decision

Items

6. Ahuriri

Regional Park development framework 9

7. State

of Our Environment 3-yearly Synthesis Report 31

8. Reshaping

of the Protection and Enhancement Programme 35

Information

or Performance Monitoring

9. Organisational

Ecology by Dr Edgar Burns 41

10. Regenerative

agriculture research project 43

11. Right

Tree Right Place: Year 1 Report and Year 2 Programme 45

12. March/April

2022 double rain events – Flood scheme impacts, recovery and lessons

learned 57

13. Gravel

Extraction - current situation and new global consent 77

14. Karamu

Urban Catchment Advisor 83

15. Catchment

Engagement framework for policy implementation 89

16. Deer

Management 97

17. Discussion

of minor items not on the Agenda 105

Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

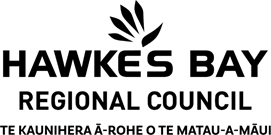

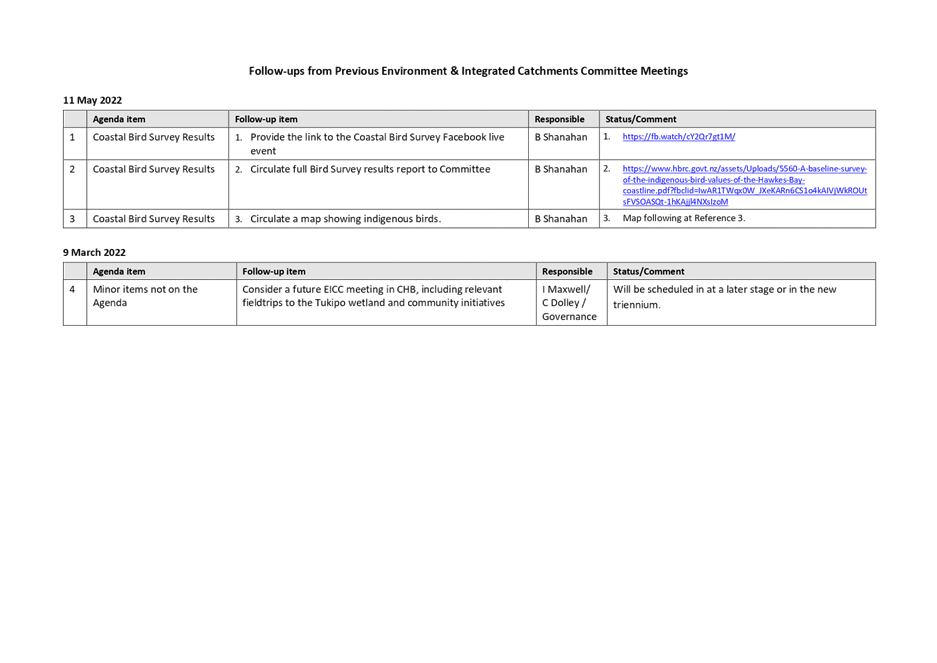

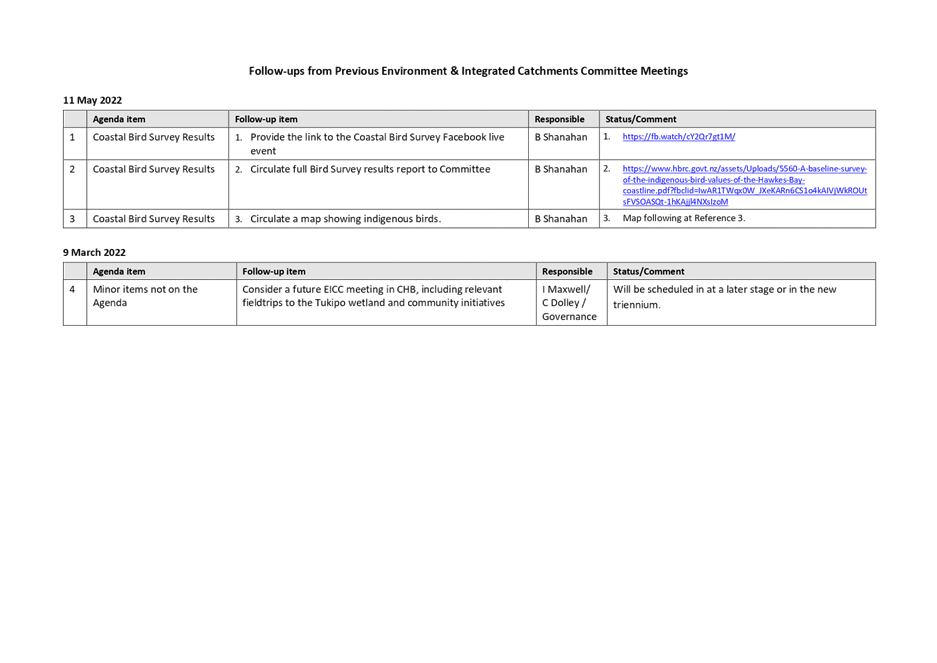

Subject: Follow-ups from

previous Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee meetings

Reason for Report

1. On the list attached are

items raised at previous Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee

meetings that staff have followed up on. All items indicate who is responsible

for follow up, and a brief status comment. Once the items have been reported to

the Committee they will be removed from the list.

Decision Making Process

2. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision-making

provisions do not apply.

Recommendation

That the Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee receives and notes the Follow-ups from

previous Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee meetings.

Authored by:

|

Annelie Roets

Governance Advisor

|

|

Approved by:

|

Chris Dolley

Group Manager Asset Management

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment

Management

|

Attachment/s

|

1⇩

|

Follow-ups from previous Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee meetings

|

|

|

|

Follow-ups from previous Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee meetings

|

Attachment

1

|

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject: Call for minor items not on

the Agenda

Reason

for Report

1. This item provides the

means for committee members to raise minor matters relating to the general business of

the meeting

they wish to bring to the attention of the meeting.

2. Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council standing order 9.13

states:

2.1. “A meeting may discuss an

item that is not on the agenda only if it is a minor matter relating to the

general business of the meeting and the Chairperson explains at the beginning

of the public part of the meeting that the item will be discussed. However, the

meeting may not make a resolution, decision, or recommendation about the item,

except to refer it to a subsequent meeting for further discussion.”

Recommendations

That the Environment and Integrated

Catchments Committee accepts the following Minor items not on the Agenda

for discussion as item 17.

|

Leeanne

Hooper

Governance

Team Leader

|

James

Palmer

Chief

Executive

|

Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject:

Ahuriri Regional Park development framework

Reason for Report

1. This item seeks the

Committee’s recommendations to the Regional Council for the establishment

of a joint committee to provide governance guidance and oversight for the

development of Ahuriri Regional Park.

Officers’

Recommendations

2. Regional Council staff

recommend that the Committee reviews and considers the information provided

about the establishment of the Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee and

provides feedback, including on the proposed Terms of Reference, to enable

Council’s agreement to establish the joint committee.

Background

/Discussion

3. The Ahuriri Regional Park

Working Group (ARPWG) was formed in June 2020 to develop a concept that was

identified in Napier City Council’s Ahuriri Estuary and Coastal Edge

Masterplan (2018) into a project suitable for funding via the Long Term Plan

(LTP). This Working Group consisted of members from Napier City Council (NCC)

and Hawke’s Bay Regional Council (HBRC), and worked closely with the yet

to be formalised Te Komiti Muriwai o te Whanga (Te Komiti) to ensure the

project was consistent with the vision set by Te Komiti to deliver enhancements

to biodiversity, ecosystems, water quality, and cultural values for the

estuary.

4. At the NCC Future Napier

Committee meeting on 11 November 2021, the Committee considered a paper from

the ARPWG and resolved, in relation to the Ahuriri Regional Park, to:

4.1. Endorse that the future

park to be located at Lagoon Farm be a platform for climate resilience and city

sustainability, delivering flood mitigation, stormwater quality, biodiversity

and estuarine restoration.

4.2. Endorse that the boundary

of the park currently known as the Ahuriri Regional Park be confined to the

legal boundaries of Lagoon Farm (Lot 1 DP 388211).

4.3. Endorse the preparation of

a masterplan for the park currently known as the Ahuriri Regional Park and the

appointment of an independent project manager.

4.4. Endorse officers exploring

options for project governance structures for the purpose of endorsing a draft

masterplan (including a multi-party Regional Committee), for consultation to be

brought back for Council consideration next year.

5. With funding being

allocated in both NCC and HBRC’s LTPs for this project, it is now desirable

to establish an appropriate governance structure to support the next phase of

the project.

Options

6. On 14 February 2022,

representatives of HBRC and NCC met with Mana Ahuriri Trust with the intention

of entering into a three-way partnership to progress this project. Options for

a governance structure were considered, including:

6.1. Joint Committee

6.2. Working Group

6.3. 50/50 ownership.

7. Although there are pros and

cons for each option, the ARPWG considered a joint committee (JC) structure

offers the following benefits:

7.1. Provides a vehicle for true

co-governance of the project.

7.2. JC is able to make

recommendations to each partner for decision-making.

7.3. Provides greater formality

for decision-making via established decision-making processes of each partner.

7.4. Use of JC structure has a

proven success record with, for example, the Clifton to Tangoio Coastal Hazards

Strategy and Hawke’s Bay Drinking Water Governance joint committees.

8. The options available to

the Regional Council are to:

8.1. Agree to establish the

Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee in partnership with Napier City Council

and Mana Ahuriri Trust, including:

8.1.1. Adopting the proposed Terms

of Reference (either as proposed or with immaterial amendments proposed for

subsequent agreement by NCC and MAT)

8.1.2. Appointing councillors

Hinewai Ormsby and Neil Kirton as the HBRC-nominated Joint Committee members,

and Councillor Martin Williams as the alternate (or appointing alternative JC members).

8.2. Agree to establish the

Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee subject to agreement by Napier City

Council and Mana Ahuriri Trust to:

8.2.1. Include additional parties

as members of the joint committee

8.2.2. Make material amendments to

the Terms of Reference as agreed by EICC today.

8.3. Not agree to establish a

Joint Committee for the Ahuriri Regional Park project.

Development

of the preferred option

9. The Ahuriri Regional Park

Working Group (ARPWG) was established to progress the project to the point of

receiving funding in the councils’ Long Term Plans. Now that this

milestone has been reached, options for the governance of the project through

its next phase have been considered by the ARPWG, with a Joint Committee being

determined as the most appropriate, and an invitation extended to Mana Ahuriri

Trust to be equal partners.

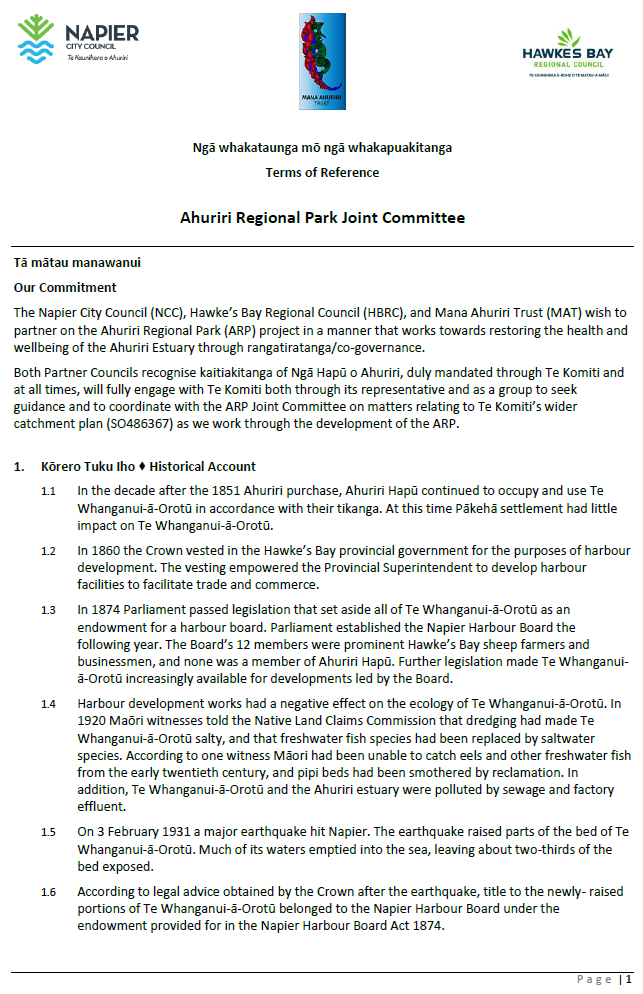

10. The Terms of Reference

(ToR) establish the ‘rules of engagement’ and expectations for each

party. The ToR is based on the Clifton to Tangoio Coastal Hazards Strategy

Joint Committee, and has been through a number of iterations with the Working

Group and Mana Ahuriri Trust nominees. The proposed ToR has also received legal

review by NCC, with the conclusion that the establishment of this Joint

Committee is provided for in the Local Government Act 2002, and there is

precedent for it.

11. Councillor Hinewai Ormsby

has co-chaired the Ahuriri Regional Park Working Group alongside NCC Councillor

Annette Brosnan. Councillors Neil Kirton and Martin Williams have also been involved

as members of the Working Group. Nominating these HBRC representatives to form

part of the Joint Committee is intended to ensure continuation of governance

oversight from the inception phase through to the project’s planning

phase.

12. The purpose of the Terms of

Reference) is to define the responsibilities of the JC as delegated by the

partner councils (NCC and HBRC) under the Local Government Act, and to provide

for the administrative arrangements of the JC. The ToR establishes:

12.1. the number of JC members

from each partner

12.2. the purpose of the JC and

its decision-making delegations

12.3. how the JC will work

alongside Te Komiti Muriwai o te Whanga

12.4. matters relating to

administrative support, including meetings, voting, remuneration, leadership,

and reporting.

13. It is proposed that the JC

is made up of two elected members each representing NCC and HBRC, and four

members from Mana Ahuriri Trust. Each partner entity is also invited to

nominate one alternate representative. This represents a true and equal

partnership between the councils and Mana Whenua.

14. Mana Ahuriri Trust Board

will be considering a similar paper to adopt the Terms of Reference on 30 June

2022, and has nominated their members, who are:

14.1. Tania Eden

14.2. Allana Hiha

14.3. Chad Tareha

14.4. Maree Brown

14.5. an alternate yet to be

decided.

15. The two elected members

nominated by the NCC Future of Napier Committee on 16 June 2022 are

councillors Annette Brosnan and Keith Price, and Councillor Hayley Browne as

alternate.

16. The two elected members

recommended to be nominated to represent HBRC are councillors Hinewai Ormsby

and Neil Kirton, and Councillor Martin Williams as the alternate.

Issues

17. Currently Lagoon Farm is in

freehold title and solely owned and managed by NCC. It has been earmarked

for future stormwater detention for the City. Entering into a partnership of

this nature will mean that future development of this site may be significantly

influenced by Ahuriri Regional Park JC recommendations. The purpose of the JC

is to make recommendations, with decisions still lying with each Partner where

these have the delegated power to do so.

18. Parties to the JC may seek

to make changes to the ToR as they move through the process of approving them.

The resolution of the Future of Napier Committee was:

18.1. Approve in principle the

Terms of Reference for the Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee (Doc Id

1471630), allowing for minor inconsequential changes being made by each partner

as required

19. If the Regional Council approves the

proposed ToR in principle, allowing for minor, inconsequential changes to be

made, then the ToR can proceed unhindered. However, if the Regional Council

requests more substantial changes, the ToR will need to be referred back to

both NCC and MAT for agreement prior to proceeding, and require further

consideration and resolution at a future Regional Council meeting.

20. Legal advice sought by NCC

on the ToR concluded that, on balance, the Local Government Act 2002 provides

for the ability to form a JC with both Council partners and mana whenua

entities, and that there is precedent in doing so. Clarity on the powers

delegated to the JC (and those that aren’t) is essential for ensuring

clear expectations from all parties, and the ToR has been drafted accordingly.

Significance

and Engagement Policy Assessment

21. All Partners acknowledge

that there are a significant number of stakeholders in the establishment of an

Ahuriri Regional Park, and that the project team, once established, will work

closely with these stakeholders throughout the course of the project and

beyond. As noted in the Joint Committee Terms of Reference, the Project

Manager, once appointed, will report to Napier City Council and its Partners on

a regular basis in relation to the project itself.

22. The NCC Significance and

Engagement Policy provides clarity on how and when the community can expect to

be engaged, depending on the degree of significance of the issue, proposal and

decision. The formation of a Joint Committee and its accompanying ToR do not

meet the criteria under this Policy for consultation.

23. The NCC Policy further

states that while Lagoon Farm is not listed as a Strategic Asset, decisions

made in relation to the future use and development of the property may have a

high level of community interest. In addition, should part of the property be

used as an integral part of the city’s stormwater network (e.g. retention

areas) in the future, then this would be classed as a strategic asset and may

require public consultation.

24. It is worth noting that the

concept of the Ahuriri Regional Park has already been through both of the NCC

and HBRC LTP public consultation processes.

Financial

and Resource Implications

25. NCC is the Council that

will facilitate the Joint Committee under its policies and processes

26. The Terms of Reference

specifies a 50/50 NCC HBRC split of costs associated with remunerating the Mana

Whenua partners to the Joint Committee.

27. The HBRC Council Meetings

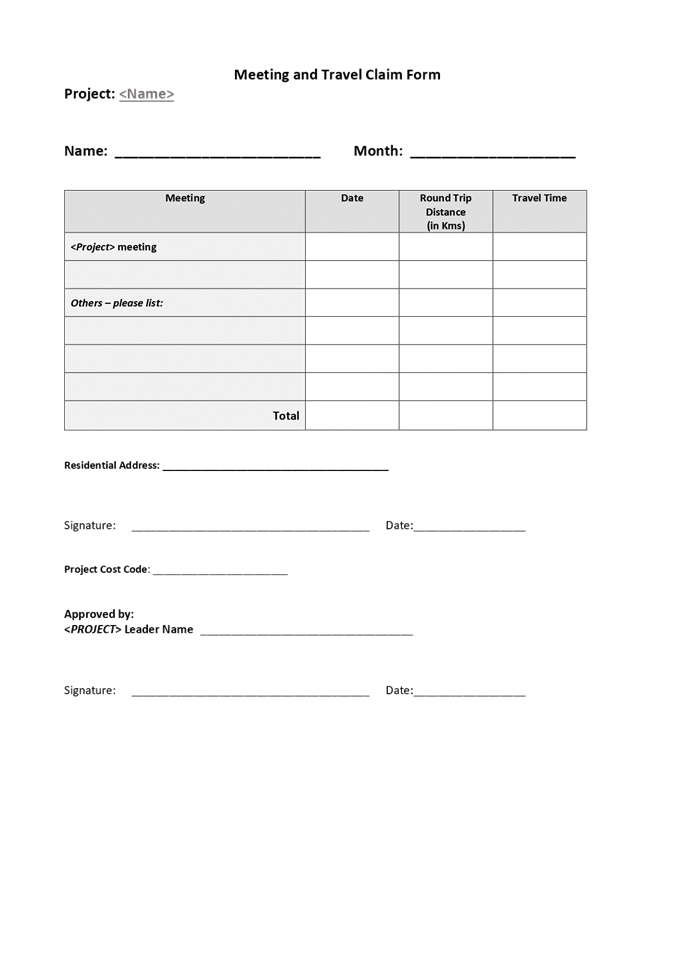

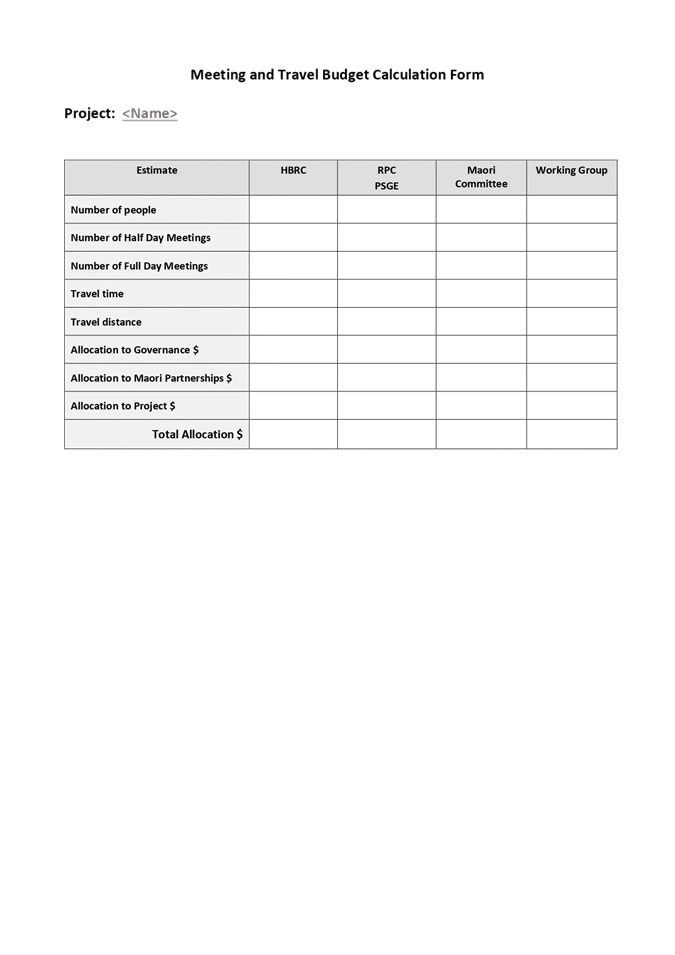

Remuneration Policy is applicable to the remuneration of non-elected Council

officials. NCC does not have an applicable policy, and so the ToR adopts the

HBRC Policy. A copy of the HBRC Policy for Reimbursement for Project Meetings

and Travel is attached.

Social

& Policy

28. The Ahuriri Estuary and

Coastal Edge Masterplan (NCC) identified the exploration of the regional park

concept for Lagoon Farm, including stormwater management and enhancement of

biodiversity and cultural values, as an initiative of priority. The concept

gained significant support from stakeholders and the wider public. It was clear

early on that partnership with Te Komiti Muriwai o te Whanga was essential as

the project would be a significant contributor to delivering on the purpose of

Te Komiti, and the masterplan would operate alongside Te Muriwai o te Whanga

Plan for the wider estuary catchment. Co-governance with HBRC and Mana Ahuriri

Trust is a commitment to working collaboratively from the very outset and at

all levels.

Risks

29. As noted above, the primary

risk is in relation to entering into an equal partnership with both NCC and MAT

in a manner that the JC can make recommendations on the future use and

development of a Napier City Council-owned asset. It is noted however, that the

ToR afford the power for the JC to make recommendations only, and that the

decision-making power still lies with each Council and the MAT Board in terms

of their respective interests.

Opportunities

30. The risks of establishing a

Joint Committee for the Ahuriri Regional Park project cannot be considered

without also highlighting the opportunities. This project, and the governance

structure established to guide and support it, is an opportunity to tangibly

work in partnership toward common goals on a project that will benefit

everyone. There will no doubt be challenges along the way that will test the

resolve of the partnership, but each Partner has committed to working through

these in good faith, and as a result there is significant opportunity to

strengthen our ties and reach out to all corners of the community to deliver

what will be a legacy project for the region.

Other Considerations

31. As with all committees, the

Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee (ARPJC) will be discharged at the end of

September 2022 ahead of the local elections and subsequently re-established by

agreement between Napier City and Hawke’s Bay Regional councils as part

of their new 2022-2024 governance structures.

32. Alternatively, NCC and HBRC

could each resolve that the ARPJC is not discharged under LGA Schedule 7 s30(7)

and that replacement members for each of the councils will be appointed

following the election. In this case, mana whenua members’ membership

would be unaffected.

Decision Making Process

33. Council and its committees

are required to make every decision in accordance with the requirements of the

Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed the requirements in

relation to this item and have concluded:

33.1. The decision does not

significantly alter the service provision or affect a strategic asset, nor is

it inconsistent with an existing policy or plan.

33.2. The use of the special

consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

33.3. The decision is not

significant under the criteria contained in Council’s adopted

Significance and Engagement Policy.

33.4. The establishment of a

Joint Committee is provided for by LGA clause 30(1)(b).

33.5. Given the nature and

significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also the persons

likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions made, Council

can exercise its discretion and make a decision without consulting directly

with the community or others

having an interest in the decision.

Recommendations

1. That the Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee receives and considers the Ahuriri Regional

Park development framework staff report.

2. The Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee recommends that Hawke’s Bay Regional Council:

2.1. Agrees that the decisions

to be made are not significant under the criteria contained in Council’s

adopted Significance and Engagement Policy, and that Council can exercise its

discretion and make decisions on this issue without conferring directly with

the community or persons likely to have an interest in the decision.

2.2. Agrees to the establishment

of the Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee

2.3. Adopts the Terms of

Reference as proposed, allowing only for minor immaterial changes

2.4. Appoints councillors

Hinewai Ormsby and Neil Kirton as the Regional Council’s Joint Committee

representatives, and Councillor Martin Williams as the alternate.

Authored & Approved by:

|

Chris Dolley

Group Manager Asset Management

|

|

Attachment/s

|

1⇩

|

Ahuriri Regional Park Joint

Committee Terms of Reference

|

|

|

|

2⇩

|

Policy for Reimbursement for Project

Meetings and Travel

|

|

|

|

Ahuriri Regional Park Joint Committee

Terms of Reference

|

Attachment

1

|

|

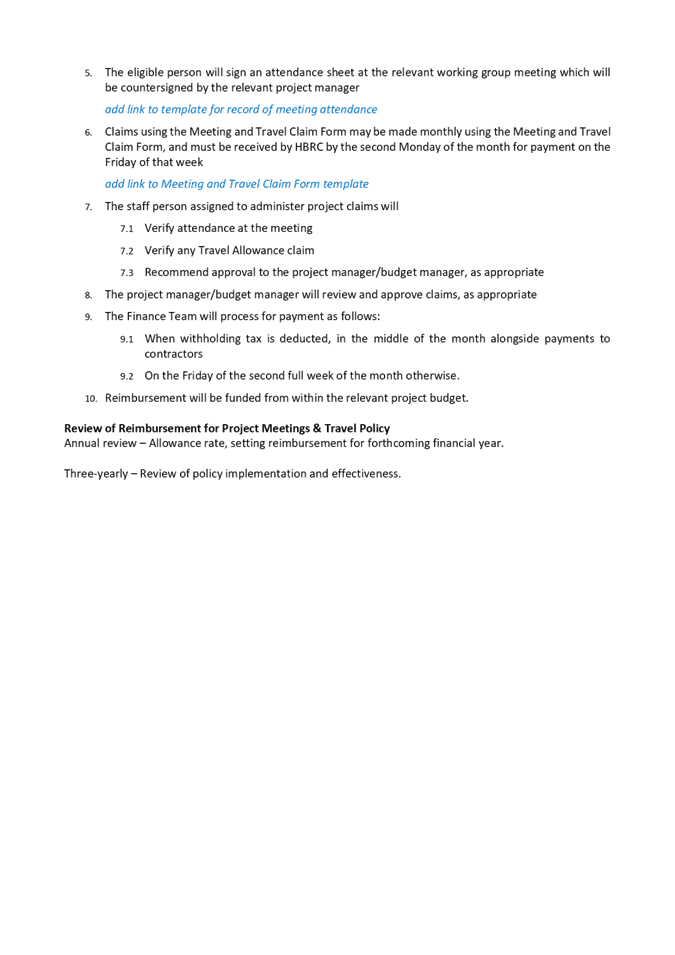

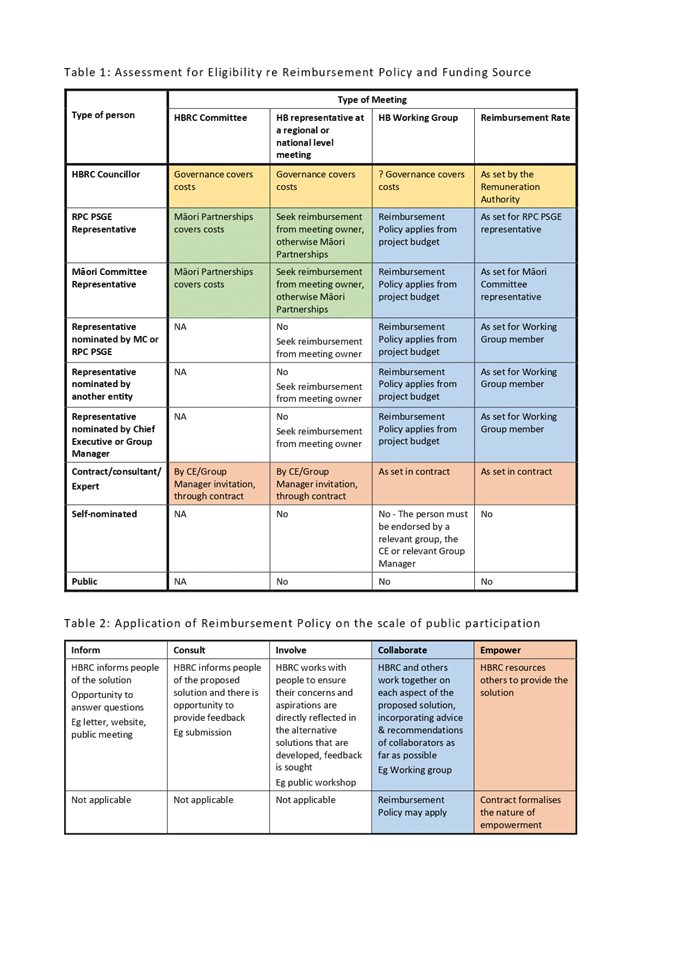

Policy for Reimbursement for Project Meetings and Travel

|

Attachment

2

|

Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject:

State of Our Environment 3-yearly Synthesis Report

Reason for Report

1. This item presents the Hawke’s

Bay State of our Environment 2018-2021 Report. This report gives an

overview of the state of the Hawke’s Bay environment, including

biodiversity and ecosystem health, climate, our coast, and air and water

quality.

2. Staff will deliver a

presentation of the key highlights of this report for:

2.1. Climate and Air

2.2. The Wairoa/Northern Coast

Catchments

2.3. The Mohaka Catchment

2.4. The Esk and Central Coast

Catchments

2.5. The Tūtaekurī,

Ahuriri, Ngaruroro and Karamū Catchments

2.6. The Tukituki Catchment

2.7. The Pōrangahau and

Southern Coast Catchments

Officers’

Recommendation

3. Staff recommend that the

report is adopted for publication.

Executive

Summary

4. Delivery of the State of

the Environment report is required by the Resource Management Act at no less

than 5 yearly intervals.

5. This report describes the

state of our natural resources and provides an evidence basis to support

decision making for the wider organisation and Council.

Background

/Discussion

6. State of the Environment

(SoE) reporting provides an environmental scorecard and assessment for

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council, communities and stakeholders to identify

and evaluate environmental conditions and pressures throughout the

Hawke’s Bay region.

7. In the time since the

publication of the previous SoE report for Hawke’s Bay (2013-2018),

central government has raised the bar for assessment and reporting. In

particular, the Essential Freshwater package was adopted in 2020 and includes

amendments to the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM).

The NPS-FM requires regional councils to report on the extent to which

long-term visions for the environment have been achieved, along with whether

the NPS-FM requirements have been met.

8. The NPS-FM also requires

information on environmental pressures, causes of issues, actions to address

issues, and an ecosystem health scorecard. Scorecard reports must also be

written in a way that “members of the public are likely to understand

easily.”

9. This SoE report takes a

different direction to previous reports for the Hawke’s Bay region by

aiming to be less technical than previous SoE reports, reporting at both

regional and catchment scales, providing greater context on environmental

pressures and restoration actions throughout the Hawke’s Bay region, and

adopting a more integrated ki uta, ki tai approach by considering interactions

among land, water, ecosystems, and receiving environments.

10. This report will be

particularly relevant for informing Kotahi dialogue alongside changes to the

Regional Resource Management Plan (RRMP) and Regional Coastal Environment Plan

(RCEP), which promotes the sustainable and integrated management of

Hawke’s Bay land, water and coastal resources.

11. The report is designed as

independent chapters based by topics or place. Topics include:

11.1. Regional biodiversity

(chapter 2)

11.2. Regional air quality

(chapter 3)

11.3. Regional climate (chapter

4)

11.4. Braided rivers (chapter 5)

11.5. Regional groundwater

quantity (chapter 6)

11.6. Regional groundwater

quality (chapter 7)

11.7. Regional river flows

(chapter 8)

11.8. Regional ecosystem health

(chapter 9)

11.9. Regional sediment story

(chapter 10)

11.10. Regional nitrogen story (chapter 11)

11.11. Regional phosphorus story (chapter 12)

11.12. Human health and recreational (chapter

13)

11.13. Regional marine and coast (chapter

14).

12. Place-based land and water

sections include:

12.1. The Wairoa/Northern Coast

Catchments (chapter 15)

12.2. The Mohaka Catchment

(chapter 16)

12.3. The Esk and Central Coast

Catchments (chapter 17)

12.4. The Tūtaekurī,

Ahuriri, Ngaruroro and Karamū Catchments (chapter 18)

12.5. The Tukituki Catchment

(chapter 19)

12.6. The Pōrangahau and

Southern Coast Catchments (chapter 20).

13. Authoring staff will

present a summary of the report to Council that explains the key

messages. The report will then be released as an online-only publication.

Strategic Fit

14. The SOE report provides an

evidential basis for measuring success of HBRC’s strategic goals.

15. It aligns with HBRC’s

priority areas of:

15.1. Water quality, safety and

climate-resilient security

15.2. Climate-smart and

sustainable land use

15.3. Healthy functioning and

climate-resilient biodiversity

15.4. Sustainable and

climate-resilient services and infrastructure.

Significance

and Engagement Policy Assessment

16. The decision is not

significant under the criteria contained in Council’s adopted

Significance and Engagement Policy.

17. The SOE report will be

shared with the public once adopted by Council.

Other Considerations

18. Due to the extent of

material covered in the SOE report and the limited time to present it in a

committee meeting, staff will be available to attend an All Governors hui to

workshop the material at a later date.

Decision Making Process

19. Council and its committees

are required to make every decision in accordance with the requirements of the

Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed the requirements in

relation to this item and have concluded:

19.1. The decision does not

significantly alter the service provision or affect a strategic asset, nor is

it inconsistent with an existing policy or plan.

19.2. The use of the special

consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

19.3. The decision is not

significant under the criteria contained in Council’s adopted

Significance and Engagement Policy.

19.4. The persons affected by

this decision are all persons with an interest in the region’s management

of natural and physical resources under the RMA

19.5. Given the nature and

significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also the persons

likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions made, Council

can exercise its discretion and make a decision without consulting directly

with the community or others

having an interest in the decision.

Recommendations

1. That the Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee receives and considers the Hawke’s Bay

State of Our Environment Report 2018-2021.

2. The Environment and

Integrated Catchments Committee recommends that Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council:

2.1. Agrees that the decisions

to be made are not significant under the criteria contained in Council’s

adopted Significance and Engagement Policy, and that Council can exercise its

discretion and make decisions on this issue without conferring directly with

the community or persons likely to have an interest in the decision.

2.2. Adopts the Hawke’s Bay State of

Our Environment Report 2018-2021 for publication.

Authored by:

|

Anna Madarasz-Smith

Manager Science

|

|

Approved by:

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment

Management

|

|

Attachment/s

|

1

|

2018-2021 State of the Environment

Report

|

|

Under Separate Cover

|

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject: Reshaping of the Protection

and Enhancement Programme

Reason for Report

1. This item seeks the

Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee’s recommendation to

Council to change the delivery model for the Protection and Enhancement

Programme (PEP) to include a contestable community Environmental Enhancement

Fund along with an expansion of our Targeted Catchment Work Programme.

Executive

Summary

2. A review was undertaken of

the delivery of the $1M PEP projects, assessing the spend of internal staff

time relative to the money spent on physical on-ground project delivery while

also evaluating how other Regional Councils' are implementing similar

environmental funds.

3. The key recommendation from

the review was that HBRC should no longer seek to lead projects in the

Protection and Enhancement space but instead, look to support and facilitate

organised landowners and/or community groups to deliver environmental projects

throughout the region that meet our strategic objectives.

4. This will allow HBRC

greater flexibility to increase the delivery of significant environmental

projects that are not currently eligible for funding through our existing

programs. This addresses a community need and will also improve synergy between

ICM funding programmes.

5. Therefore, it is proposed

that the $1M allocated to the PEP be split into two fund categories:

Environmental Enhancement Fund (EEF) and Targeted Catchment Work (TCW) - with

the implementation of these set to begin in the 2022-2023 financial year.

Background

/Discussion

6. In 2017 as part of

the Annual Plan development, the PEP (formerly Environmental Hot Spots)

was established to accelerate on-ground action on six identified

high-priority environmental 'hot spots' throughout the region – Ahuriri

Estuary, Karamu River, Lake Tūtira, Lake Whakakī, Tukituki

River, Lake Whatumā and our Marine environment.

7. These initiatives were

proposed with a focus on leveraging the Ministry for the Environment’s

Freshwater Improvement Fund (FIF). HBRC was successful in gaining funding for Tūtira (Te

Waiū o Tūtira, a 4-year project 2018 - 2022) and

Whakakī (sunshine, wetlands and bees will revitalise the taonga

of Whakakī, a 5-year project 2019 - 2024).

8. Over the past 5 years, the

PEP has enabled HBRC to build important relationships and work with

stakeholders and Treaty partners to deliver a significant volume of on-ground

work. This has been implemented at the catchment/sub-catchment scale to

initiate the long-term restoration of these key ecosystems through enhancing

biodiversity and water quality.

9. However,

numerous issues have been experienced throughout the duration of

the Tūtira and

Whakakī FIF projects that have

impacted the ability to successfully deliver the projects’ full

sets of objectives. These issues have primarily revolved around relationship

management with key stakeholders and the inability to obtain unanimous approval

to complete some of the more ambitious project objectives.

10. Ultimately, this resulted

in HBRC having to hold/carry forward significant funding that was attached to

these projects over several years without the flexibility to redirect funding

to other opportunities as they arose. HBRC also invested considerable staff

resources to obtain resolutions for the issues affecting these projects.

11. During the same timefame,

the ICM Group implemented the Erosion Control Scheme and funded Priority

Ecosystem site restoration work throughout the region. The successful delivery

of these programmes has highlighted additional areas of work not being

addressed through our existing funding programmes that could be targeted

through the PEP.

12. There has been sustained

growth in the interest and awareness of the environmental issues we are facing

across the region. This has come from a diverse cross-section of the community many

of whom are wanting to take ownership and lead the delivery of projects to

contribute to the restoration of the regions environment.

13. This has driven an

increased demand for funding from a wide range of people/groups/agencies who

are motivated to achieve outcomes in line with HBRC’s strategic focus.

14. A review was undertaken to

consider how money has flowed across the PEP projects and the amount of

internal staff time spent relative to the money spent on physical project

delivery, while also evaluating how other Regional Councils' are implementing

similar environmental funds.

15. This highlighted that many

other Regional Councils across the motu were operating an annual contestable

fund to support community and catchment groups to deliver environmental

enhancement and biodiversity projects.

Options

Assessment

16. As a result of the review,

the following core principles were developed as a recommendation to provide

clear guidance for the future of the PEP.

17. HBRC will no longer seek to

lead projects in the protection and enhancement space but, instead, look to

support and facilitate organised landowners and/or community groups to deliver

environmental projects throughout the region that meet our strategic

objectives.

18. This allows HBRC more

flexibility to target the delivery of significant environmental projects that

are not currently eligible for funding through our existing programmes. This

not only addresses a community need and will also improve synergy between ICM

funding programmes and increase region-wide delivery of environmental outcomes.

19. Community and catchment-led

groups have an increasingly crucial role to play in the future improvement and

management of the region's environment. A key aspect of the PEP will be to

build/strengthen key relationships with external groups and support them to

build capacity and capability in the delivery of environmental projects.

20. Moving forward it is

proposed that the PEP has two fund categories: Environmental Enhancement

Fund and Targeted Catchment Work. Both are outlined below with the

implementation of these set to begin in the 2022-2023 financial year:

Environmental

Enhancement Fund

|

Fund Category

|

Detail

|

Budget

|

|

Environmental

Enhancement Fund

|

This is a contestable fund available to established

Catchment and Community Groups. Providing these groups, with a model for

successful project delivery. Allowing them to build capacity to seek funding

from other external sources.

Assessment criteria are based on our strategic

objectives and level of service statements and measures. Projects can be up

to two years and applicants can apply for further funding once the previous

project has been delivered.

Annual funding round with the applications evaluated by

a dedicated HBRC staff panel.

|

$100k p.a.

Pilot for the first 3 years

Min. $5k per

project

Max. $25k

per project

|

21. The following

groups/organisations would be eligible to apply for funding through the EEF:

21.1. Community groups

21.2. Iwi/hapu

21.3. Kaitiaki groups

21.4. Incorporated societies

21.5. Community trusts

21.6. Resident and ratepayer

groups

21.7. Landowner groups (e.g.

Landcare or Streamcare groups)

21.8. Tertiary education

institutions

21.9. Businesses and industries.

22. Projects for the EEF would

be assessed by the following criteria.

22.1. Applications of up to a

maximum of $25,000 ex GST.

22.2. Projects that encourage appropriate

public access to the project site.

22.3. Projects/activities within

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council’s legal boundaries and areas of

responsibility.

22.4. Fit with Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council’s strategic outcomes and policies – how the

project contributes to Council’s LTP outcomes.

22.5. Environmental protection

and enhancement – is there a clear need for the project, and how the

project will directly promote, enhance or protect the region’s

environment.

22.6. Community participation

& awareness – how the project involves iwi Māori, the wider

community and increases public awareness of environmental issues.

22.7. Value to Mana Whenua

– how the project involves iwi Māori including their cultural

values, interests and associations, the effect on Māori historic heritage

or the relationship of Māori and their culture and traditions with their

ancestral lands, water, sites, wāhi tapu and other taonga including fauna

and flora.

22.8. Viability – the

likelihood of the project’s success and the applicant’s capability

to deliver the outcomes of the project. Desirable attributes include a robust

project plan, a project budget providing visibility of all funding sources for

the project and a clear method for monitoring the success of the project.

22.9. Budget - does the project

represent value for money and is the project suitably allocated to achieve the

desired outcomes.

23. In the majority of cases,

HBRC expects funding to be released via advanced partial payment (up to 80% of

the total project value) rather than upon project completion. This is due to

the fact the majority of the community/catchment groups are in their infancy

and not expected to be holding significant finances to operate via payment in

arrears.

24. Advanced partial payment

has shown to be the most common approach taken by other Regional Councils in

the implementation of community funds. However, there is a level of financial

risk associated with releasing funding via advanced partial payment. To

mitigate this the maximum project value has been capped at $25,000.

Targeted

Catchment Work fund

|

Fund Category

|

Detail

|

Budget

|

|

Targeted Catchment Work

|

Targeted Catchment Projects

The purpose of this fund is to deliver high-value

environmental outcomes on a catchment/sub-catchment scale such as improved

water quality, riparian protection, biodiversity enhancement, wetland

development.

The place-based constraints that were established with

the original Hotspot fund will be removed to allow greater regional flexibility

in the delivery of this programme.

Target areas where we have established good

relationships with landowners to provide further subsidies for work that

falls outside the eligibility of the ECS/EP funds but substantially

contribute to the delivery of our strategic outcomes and in turn provide a

good return on investment.

Can be multi-year projects, with a 60% subsidy with

landowners.

Internal Targeted Projects

A portion of this fund (up to 100k p.a.) will be

available for cross-council investment to partner for specialised projects

that have strong environmental outcomes, innovation and build key external

relationships such as the proposed Inanga Enhancement Programme, eDNA

Monitoring Programme etc.

|

$500k p.a.

HBRC Min. $2K per project

HBRC Max. $30K per project

|

|

Marine Protection and Enhancement Project

This is a continuation of the existing Marine

Protection and Enhancement Project. Funding is dedicated to investment in our

scientific understanding of our marine environment and

systems. Supporting the delivery of work including multibeam echo-sounding

surveys of the seabed; sediment surveys of Hawke’s Bay to provide

modelling, and fencing and planting to protect the remnant seagrass beds.

|

$200k p.a.

|

|

Staff cost and overheads

|

The annual cost of the Programme Manager Protection and

Enhancement Fund is covered by the fund.

|

$200k

p.a.

|

25. The primary aim of the TCW

is to assist on-ground works and actions by providing advice and assistance in

programme development and implementation.

26. Project plans will be

developed in partnership with HBRC Catchment Delivery staff and on-ground works

delivered through a subsidy scheme (60% HBRC 40% Landowner/Catchment Group) to

projects that protect and enhance our freshwater and land resources.

27. The fund has been designed

to complement the Erosion Control Scheme and the Priority Ecosystem Programme

by covering works and activities that do not meet their funding criteria but

will contribute to significant environmental improvements and meet our existing

strategic outcomes.

28. A comprehensive approach

will be taken to target on-ground environmental enhancement activities with

projects being able to cover multiple properties at the sub-catchment or

catchment scale.

29. Project eligibility for the

TCW would be determined by the following criteria:

29.1. Projects must address one

or more of the following: erosion prevention, biodiversity enhancement,

ecosystem restoration, improvement in water quality, stream, or wetland habitat

creation or improvement, plant/animal pest management.

29.2. Projects must contribute to

high-value environmental outcomes at a catchment or sub-catchment scale.

29.3. Applicants must provide a

40% funding match in the form of cash, labour, and/or donated materials.

29.4. Projects must be within the

Hawke’s Bay regional boundary. If the project is applied for by a

‘group’, landowners whose land the project covers must provide

written approval.

29.5. Project length and size are

not limited but will be subject to annual funding availability.

29.6. Project goals can overlap

with ECS and PEP projects.

30. Examples of projects that

would be delivered through the TCW would include but not be limited to the

following:

30.1. Riparian and streambank

stabilization, retirement and enhancement (planting, pest control) –

where not required by legislation.

30.2. Wetland restoration or

development.

30.3. Plantation to permanent

forest cover conversion.

30.4. Phosphorus/sediment detainment

bund establishment.

30.5. Retirement and native

forest reversion.

Strategic Fit

31. Due to this being a new

approach for delivering the PEP, there is currently no Level of Service

Statements (LOSS) or Levels of Service Measures (LOSM) attached to the programme. However, specific LOSM will be developed

at the next point of review.

32. Notwithstanding this, the proposed changes

to the PEP outlined in this report

align with Council’s strategic plan, priority areas and associated

objectives for sustainable land use, biodiversity and water quality. This

report seeks to streamline the delivery of the fund allowing for increased

delivery in those priority areas.

Significance and Engagement Policy Assessment

33. This matter is not

significant, as defined in Council’s significance and engagement

policy. The PEP and associated funding is already included in

Council’s 2021-2031 Long Term Plan.

Considerations of Tangata Whenua

34. There are no specific

considerations required in relation to the request made in this report as this

merely seeks to alter the method of delivery for the existing fund.

Financial and Resource Implications

35. The $1M funding for the PEP

is already included in Council’s 2021-2031 LTP. This report seeks to gain

approval to reallocate this funding to implement the changed approach to

delivery outlined above.

36. The implementation of both

the EEF and TCW will provide a detailed understanding of the resources required

to deliver these funds at a larger scale. Staff will then be in a position to

engage Council on potentially expanding the value of the funds and staff

resources through the next LTP process.

Decision Making Process

37. Council and its committees

are required to make every decision in accordance with the requirements of the

Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed the requirements in

relation to this item and have concluded:

37.1. The decision does not

significantly alter the service provision or affect a strategic asset, nor is

it inconsistent with an existing policy or plan.

37.2. The use of the special

consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

37.3. The decision is not

significant under the criteria contained in Council’s adopted

Significance and Engagement Policy.

37.4. The persons affected by

this decision all those persons with an interest in the region’s

management of natural and physical resources.

37.5. Given the nature and

significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also the persons

likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions made, Council

can exercise its discretion and make a decision without consulting directly

with the community or others

having an interest in the decision.

Recommendations

That Environment and Integrated

Catchments Committe:

1. Receives and considers the Reshaping of the Protection

and Enhancement Programme staff

report.

2. Agrees that the decisions

to be made are not significant under the criteria contained in Council’s

adopted Significance and Engagement Policy, and that Council can exercise its

discretion and make decisions on this issue without conferring directly with

the community or persons likely to have an interest in the decision.

3. Approves the request to

implement the new delivery model for the Protection and Enhancement Programme.

Authored by:

|

Thomas Petrie

Programme Manager Protection &

Enhancement Projects

|

Jolene Townshend

Acting Manager Catchment Delivery

|

Approved by:

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment

Management

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no attachments for this

report.

Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject:

Organisational Ecology by Dr Edgar Burns

Reason for Report

1. This item introduces Dr

Edgar Burns’ report titled Organisational Ecology, which uses the concept of

organisational ecology to reflect on HBRC’s environmental work in our

region so we can increase our effectiveness in supporting improved environmental

practices and climate change readiness. This is the third social science report

for the Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee (EICC) in the technical

paper series.

Executive Summary

2. Selected examples and

issues of organisational ecology are discussed that can be used to enhance HBRC

delivery of its regional mandate for water soil and the growing climate

pressures faced both locally and globally.

3. This report brings a social

science lens to the HBRC role using the idea of organisational ecology to show

the complexity and opportunities of regional council work. Among many

organisational, community and sector groupings there are competing

understandings and interests. Within this ecology, only a small part of needed

changes are able to be influenced by HBRC.

Strategic Fit

4. This work delivers against 2020-25

Strategic Plan, namely that Climate change is at the heart of everything we

do.

Discussion

5. The HBRC is increasingly

faced with people pressures that interact with what science evidence is

reporting. While climate change denialism is receding, there is little

appreciation yet of the speed or severity of local consequences of climate

heating on this region and its inhabitants.

6. This is presented in the

main body of Dr Edgar Burns’ Organisational Ecology report, from the contents

page onwards.

7. Dr Burns will present the

findings of his research to Council and will be available for questions and

discussion.

Next Steps

8. Selected next steps are

proposed in the final section of Dr Burns’ report (attached).

Decision Making Process

9. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision-making provisions

do not apply.

Recommendation

That the Environment and Integrated Catchments

Committee receives and notes the Organisational Ecology report by Dr

Edgar Burns.

Authored & Approved by:

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment Management

|

|

Attachment/s

|

1

|

HBRC's Organisational Ecology

|

|

Under Separate Cover

|

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject: Regenerative agriculture research project

Reason for Report

1. This item presents a

collaborative Regenerative Agriculture research project involving AgFirst, the

Regional Council, Ministry for Primary Industries and On-Farm Research.

Executive Summary

2. Lochie McGillivray

(AgFirst) and Dr Paul Muir (On-Farm Research) will present an oral summary of a

study to investigate the impacts of regenerative agriculture within a dryland

farming operation.

3. This project aims to

improve the resilience of sheep and beef farmers in a drought prone region.

This will be achieved by testing forage types and grazing management strategies

that meet the principles and practices of a Regenerative Agriculture system.

4. However, resilience is not

just about forages and forage management, it is also about stock policy and

timely decision making. To this end the project will set up a demonstration

unit where farmers can view and then mimic the systems deployed.

5. A wrap-around extension

programme will include system economic analysis, workshops and be focused on

the demonstration farm practices with regular farm walks.

Strategic

6. This topic considers

matters that align with Councils interests in:

6.1. Smart sustainable land use

6.2. Water quality safety and

security

6.3. Healthy functioning

biodiversity

6.4. Climate adaptation and

mitigation.

Background

7. Council is investing $100K

per year for four years to support a farmlet scale study of regenerative

agriculture through the Innovations and Strategic Relationships (ISR) grant

fund that is associated with the Erosion Control Scheme. The total budget

for the project is $2.5M. This represents significant leverage into a

greater understanding of a type of farm management that has significant

potential to help Council with its ambitions in land, water, biodiversity and

climate resilience management.

8. A greater understanding of

the potential benefits of regenerative agriculture will also assist in

understanding how best to integrate this into a farming system as part of the

Right Tree Right Place collaboration with The Nature Conservancy.

9. The ISR fund has been

created to provide financial support for initiatives and

partnerships/relationships that progress the aims of the scheme within the

Hawke’s Bay region. The key objectives that the aims to achieve

are:

9.1. Reducing soil erosion

9.2. Improving water quality

through the reduction of sedimentation into the waterways

9.3. Improving terrestrial and

aquatic biodiversity through habitat protection and creation; and

9.4. Providing community and

cultural benefits through forest ecosystem services.

10. Staff are involved in both

the technical working groups and project governance.

11. Co-investors in the project

include MPI, Barenbrug NZ Seeds, Beef and Lamb NZ and Ravensdown.

12. The research will be

undertaken at the Poukawa Research farm which is well established, with over 35

years of data and research on Hawkes Bay dryland agriculture, and with the

facilities to undertake the component research and farmlet studies required for

this project. The site is in the heart of Hawkes Bay dryland and its highly variable

rainfall (range 460 – 990 mm) means it is an ideal demonstration site for

this project.

Discussion

13. Lochie and Paul will

present to Council details on the research and some initial findings.

Decision Making Process

14. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision making

provisions do not apply.

Recommendation

That the Environment and Integrated Catchments

Committee receives and notes the Regenerative Agriculture research project report

and presentation.

Authored & Approved by:

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment

Management

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no attachments for this

report.

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

6 July

2022

Subject:

Right Tree Right Place: Year 1 Report and Year 2 Programme

Reason for Report

1. This item

provides the Committee with a summary of the progress from the last year of the

Right Tree Right Place (RTRP) project and outlines the current status and

high-level pathway for year two of the project.

Executive Summary

2. Work with initial pilot

farms was aimed at developing momentum for the project and to provide learning

for subsequent phases of the project. The first seedlings will be planted on

the first pilot farm this July and farm/forestry planning has started on the

second pilot farm. Legal and tax advice is supporting the development of

commercial arrangements for HBRC finance.

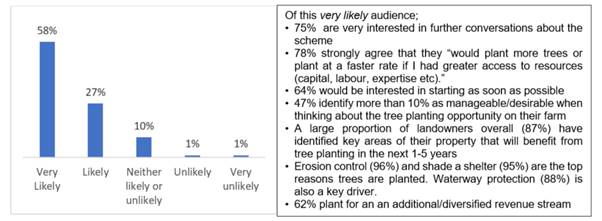

3. A recent farm survey about

perceptions of the RTRP model has shown high interest from respondents (58%

very likely to use RTRP). Survey results are supporting the prioritisation of

potential pilot farms, development of farm planning collateral and forward work

programme.

4. Developing the pipeline of

target RTRP farms has taken a structured approach with support from the

Catchment Delivery Team (CDT). The pipeline of potential farms will be used in

the business case for impact investment in the scale-up initiative.

5. A farm-planning framework

has been developed with support from lead consultants. Standardised templates

will allow information collected from farms to be used with business case

development.

6. There has been a solid

uptake of early communications about the project. Initial seedling planting and

survey results will be the subject of current comms. Landowner engagement has

now focused on priority farms in northern Hawke’s Bay catchment areas.

7. The forward work programme

will see the remaining farm/forestry plans and pilot farm selection take place

over the remainder of 2022. Impact investment business case development and

investor sounding will continue into the first half of 2023.

Project objectives

8. During the 2021-31 LTP

process, Council agreed to fund the RTRP project to address the significant

erosion problem in Hawke’s Bay through demonstrating a successful RTRP

model by refining a planting model with several objectives:

8.1. To recover its own costs

8.2. Encourage planting of trees

on erodible land

8.3. Stimulate the market to

invest in trees on farms that strengthens financial and environmental outcomes

8.4. Reducing the need for whole

farm afforestation

8.5. Plant enough trees to

prepare for climate change

8.6. Significant environmental

benefits.

RTRP

Pilot Farms

9. The early focus with pilot

farms has been to gather momentum quickly with the project in order to

incorporate the learning from the initial pilot farms into the forward work

programme. This approach will see planting on an initial pilot farm in this

planting season. It also allows a more considered approach with the remaining

pilot farms that aligns with due diligent efforts needed to underpin the

business case to scale up the RTRP concept.

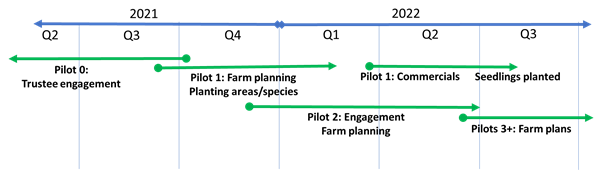

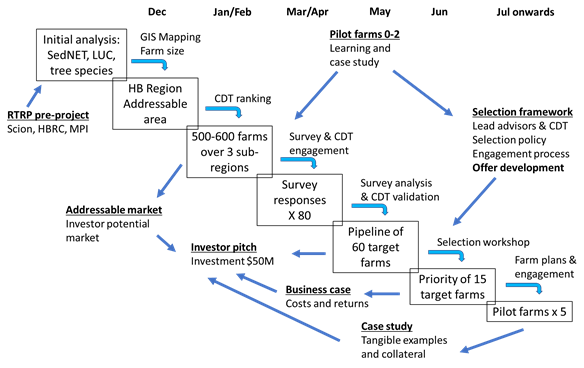

10. An illustration of timing

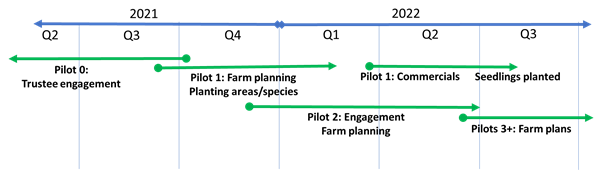

relating to the pilot farms is shown below.

Pilot

farm 0: Ruakituri

11. A farm and forestry plan

were developed for a 1200 ha farm in the Ruakituri district in northern

Hawke’s Bay as part of the RTRP business case development. This farm was

to be the first pilot farm. The farm/forestry plan identified circa 140ha of

production Pinus Radiata, 23 ha of production redwoods and 54 ha of infill

native planting.

12. Presentations were made to

trustees of the farm, comprising the farm owners, their adult children and farm

advisors. The children preferred to proceed with implementing the RTRP

initiative as outlined in the farm/forestry planning exercise, in part, to

leverage additional revenues from forestry to facilitate succession of

ownership.

13. The older generation farm

owners were not comfortable with the risks associated with production forestry

and opted to proceed with a slower implementation of redwood and native

plantings.

14. This exercise did not

result in a HBRC funded RTRP initiative. However, it did result in trees being planted

on marginal and erodible land, the primary objective of RTRP.

15. Learning from this exercise

include:

15.1. It’s a big decision

for landowners to embark on forestry options at scale, and considerable time

and energy can be expended working with complex ownership structures that may

not result in a council-financed RTRP project.

15.2. Good quality farm/forestry

plans are needed to allow evidence-based decision making but it still takes

time to build confidence to embark on a forestry journey.

15.3. Ultimately, the vision that

the landowner has for their land needs to be the primary direction of travel.

15.4. Once evidence-based

material has been developed, landowners may develop the confidence to secure

alternative (non-HBRC) sources of capital to progress with forestry options or

fund planting out of cashflow over a longer timeframe.

15.5. There are challenges in

seedling supply, especially for natives, with lead times currently in the order

of two to three years.

Pilot

farm 1: Waipapa

16. Waipapa is a 724ha farm

located approximately 45km south of Hastings in Elsthorpe district.

17. The project worked with

landowners at Waipapa to develop a farm/forestry plan through the second half

of 2021. A memorandum of understanding was developed in early 2022 with ongoing

activity to confirm tree species options and a five-year planting plan.

18. The resulting work

recommends a mix of tree species including native trees and shrubs, Cedrus

deodara (Coastal Redwood), and Pinus radiata. Initial seedlings are

to be planted in July 2022. The total planting area amounts to just over 90ha

with half planted in P.radiata and costs to establish of approximately

$470,000.

19. Legal and tax advice is

being procured to develop HBRC funding options modeled on a loan with repayment

of principle and interest from carbon revenues over about 10 years. The loan

options are secured by a Forestry Right or mortgage over land for the period of

the loan. The HBRC finance team is supporting this work.

20. Lessons and leverage from

this pilot project:

20.1. A reasonable proportion of

pines (and faster growing species) are needed to subsidise native planting.

20.2. Detailed farm/forestry

plans involving on-farm walk-overs are needed to carefully refine planting and

fencing areas, species selection, pest control and a multi-year planting

programme.

20.3. Incorporating forestry and

additional revenue streams into a pasture-based farming system provides

considerable optionality for farm management: for example, selling forestry

blocks to a neighbour or shared infrastructure, and farm management options.

20.4. Low productivity land can

also be high maintenance land: transitioning this to forestry can reduce farm

workload and free up resources to focus on productive parts of the farm or

other non-farming pursuits.

20.5. A forestry initiative on

one farm can facilitate discussions with neighbouring farms about catchment

orientated initiatives to improve environmental outcomes at catchment scale.

20.6. Forestry supports

ecological outcomes, and this dimension should be considered when selecting

tree species: in the case of Waipapa, planting kōwhai will support

migration of tūī.

Pilot

farm 2: Coastal Central Hawke’s Bay

21. Development of a

farm/forestry plan has begun for a 1,300ha coastal property southeast of

Elsthorpe. Farm trustees have an interest in extension work and ,accordingly,

the property offers good potential for case-study development and

educational-collateral development.

22. The farm offers a clean

canvas on which to develop a forestry plan and potential to pre-plan

infrastructure like roading, fencing and other facilities.

23. There are significant areas

of highly erodible land, both coastal and adjacent to waterways that will

require lateral thinking around species selection and mixed species planting

regimes. The Trust has a vision for increasing the current 60 ha of production

forestry to further plantings of production forestry and to invigorate native

regeneration.

Farmer survey

24. A farmer survey was

conducted in late 2021 to understand farmer sentiment of the RTRP concept,

interest and knowledge about planting trees and financing preferences,

knowledge and use of regenerative agricultural practises, and interest in

further discussions with the RTRP team.

25. This information is being

used to shape the future work programme, particularly in the area of landowner

engagement, farm planning processes, pilot farm selection and collateral needed

to support the programme.

26. The survey was launched in

February/March 2022 and fronted by CDT members who personally circulated the

survey and followed up directly with landowners.

27. The results were collated

and analysed in April/May and have recently been used to support development of

the project farm planning framework. Sub-regional variation to survey responses

and landowner perceptions have also been considered.

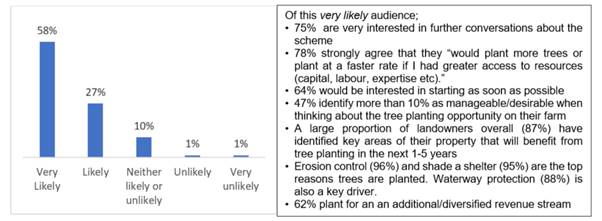

28. Of the circa 80 responses,

58% would be very likely to consider using Right Tree Right Place for

their farm.

28.1. How likely

would you be to considering using Right Tree Right Place for your farm?

29. The survey has

highlighted two areas that will require further investigation as part of the

forward work programme:

29.1. While access to

capital was identified as a constraint to planting more trees, only 13% of

survey responses indicated they would consider access to private investor

capital and associated sharing of risk and returns.

29.2. Only 28% of

survey responses strongly agreed that they are interested in applying

regenerative farming practises. However, 47% of landowners strongly agreed that

they would do more to improve soil health and protect water ways and

biodiversity if they had greater access to resources.

30. Next steps in relation to

the findings of the survey:

30.1. Project farm planning

framework is being developed

30.2. Communications about the

survey results are being developed

30.3. Validation of

survey responses and ranking of priority farms

30.4. Education and engagement

efforts will target catchment orientated initiatives

30.5. One-on-one engagement will

be tailored to account for landowner concerns and interests expressed in the

survey

30.6. Project branding,

positioning, messaging, are being reshaped

30.7. The RTRP product offering

is being defined – what are we selling?

Farm selection and CDT

31. A structured

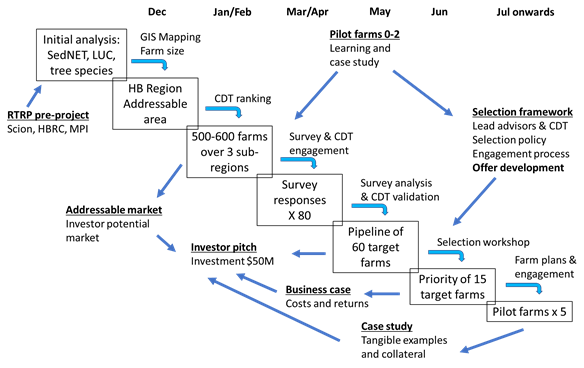

process has been taken to develop a prioritised RTRP target farm database

(pipeline of farms) as illustrated below and described in the following

narrative.

32. The CDT has been involved

in an iterative approach of learning to support the project. Initial workshops

were held in Q3/4 2021, with more detailed discussion sessions in Q1/2 2022

that focused on northern, central and southern zones. CDT members support RTRP

staff discussions with landowners, both on and off-farm; as relationship

managers.

33. In Q4 2021, the total

addressable market of potential RTRP farms was developed. This was based

on the early RTRP work authored by SCION, PF Olsen and RedAxe Forestry with

further refinements by the HBRC GIS team to identify circa 500 potential farms.

These farms were validated and graded into priority bands by the CDT team. The

addressable market will be used in the investment pitch for attracting impact

investment to scale up the RTRP concept.

34. This database of potential

farms was used for the farmer survey work. CDT members personally circulated

the farm survey to their client landowners and followed up directly with emails

and phone calls. This direct engagement with landowners was helpful to build

relationships and offered a platform to discuss other erosion control service

support.

35. Survey

responses identified those farmers with an interest in further discussions about

the RTRP model. Forums were held with the CDT members to validate survey

responses and refine farm rankings. This exercise has yielded a prioritised

pipeline of about 60 farms with an interest in the programme. This list

provides a tangible view of farms interested in afforestation support that will

be used with the impact investment pitch.

36. A workshop with

farm, forestry and regen ag consultancy leads in mid-June formalised the farm

planning framework for the balance of farm plans needed to support the

remaining pilot farm selection and due diligence work. The farm planning

framework involves:

36.1. Farm plan scope

– what’s in and what’s out

36.2. Farm plan

template of information required for impact investment business case

development

36.3. Definition and

integration of regen ag components to farm planning

36.4. Skill set;

criteria and process for the development of a consultancy panel

36.5. Peer review,

quality assurance and support process for due diligence

36.6. The RTRP offer

from the farm plan perspective – what is the pitch to landowners?

37. A subsequent

workshop was held with lead consultants and CDT members to assess the target

list of 60 farms based on pre-defined farm selection criteria to identify the

priority 15 farms that will undergo a farm planning exercise. The information

developed in the farm planning process will help select the remaining pilot

farms for HBRC funding support. It will also provide data for the development

of the business case needed to attract impact investment.

Scale up: project investment, resourcing and The Nature

Conservancy partnership

38. Building on the MPI

partnership for the early work on the RTRP concept, further discussions have

led to an MPI staff member being appointed to the project team. An application

has also been developed for funding support. MPI is supporting cross government

engagement with a focus on forestry, environmental improvement initiatives and

private/public funding models.

39. Use of the MyEnviro

software is being explored to provide a monitoring and reporting platform for

RTRP. It offers the potential for modelled and real time environmental

monitoring at both farm scale and catchment scale, and possible integration

with wider HBRC catchment initiatives

40. Supply chain constraints

have been explored, particularly for seedling supply and planting.

Interventions will be considered once the forward demand for seedling species

and timing is better understood, which is an output of the farm/forestry

planning activity.

41. Lead consultants have been

procured for agri, forestry and regen ag. The work has been guided by support

from the HBRC procurement team. The lead consultants have worked alongside CDT

members to develop the farm planning framework and forward work programme,

including the formation of a panel approach with other consultancies for farm

planning and engagement activity.

42. Discussions are

underway with processors who are progressing initiatives based on regenerative

practise certification that are resulting in market access and premium

benefits. This will support the regenerative agricultural practises that may be

incorporated into the project.

43. Investor sounding has

started alongside development of financing models for the scaled-up

proposition.

Communications and engagement

44. The formation of the

partnership with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) had widespread pickup across

media channels and support from key stakeholders to amplify the kaupapa. The

National Business Review ran the story offering a channel into the investment

community.

45. The project is broader in

perspective than just trees. It also includes adjustments required to the

pasture-based farming system as a result of planting sections of the farm.

TNC’s interest in regenerative agricultural orientated practises offer

water and land quality related benefits on top of tree planting. Opportunities

to integrate regenerative agricultural practises into the project are being

progressed.

46. As part of the due

diligence efforts for the scale up, the combined RTRP and regenerative

agriculture is being orientated as a ‘one-project approach’ and

Tracta (rural specialist marketing agency) has been engaged to explore a

potential renaming/rebranding of the project and support for more defined

messaging about the project proposition.

47. The planting of trees in

the ground at Waipapa in July will offer comms opportunities.

48. Other key upcoming

announcements will be the rebrand, survey results, and new team and structure.

49. As part of our MPI Hill

Country Erosion funded work we are progressing a 3D projection table and

Waipapa will be the feature farm. The table has the ability to project onto the

3D farm representation the current and future farming systems and associated

improvements to environmental and biological outcomes. It will be narrated by

Evan and Linda Potter and tell the story of their farm and their vision for the

next 50 years. The projection table will reside in the HBRC reception once it

has been renovated but be portable to appropriate field days and forums.

50. Farmer engagement has

centred on catchment centric forums interested in the RTRP model and one-on-one

engagement with leads generated by the CDT. Engagement has shown there is a

sub-regional variance in landowner perceptions to farm forestry.

51. Many landowners in the

southern area are already moving in the direction of RTRP thinking. The geology

of farms in this area is relatively less complex and planting areas are more

easily understood. These landowners are interested in what the RTRP offer is

and when is it available.

52. Northern areas with more

complex and more extensive erosion-prone land will require more effort.

Farm/forestry planning may be more complex. Some landowners have preconceived

thinking related to total farm afforestation. This anecdotal feedback is

supported by survey responses.

53. Good progress with

engagement has been made in the Ruakituri catchment with corresponding interest

in the RTRP model. It offers a solid base for further RTRP engagement alongside

other primary sector organisation initiatives, including HBRC initiatives in

the area.

54. The recalibrated project

timeline described below underpins the coming engagement with farmers and wider

sector. It will involve catchment-based forums and direct engagement with

target farms with an emphasis on northern Hawke’s Bay. This will be

supported by comms to survey respondents and channelled through appropriate

channels and stakeholders.

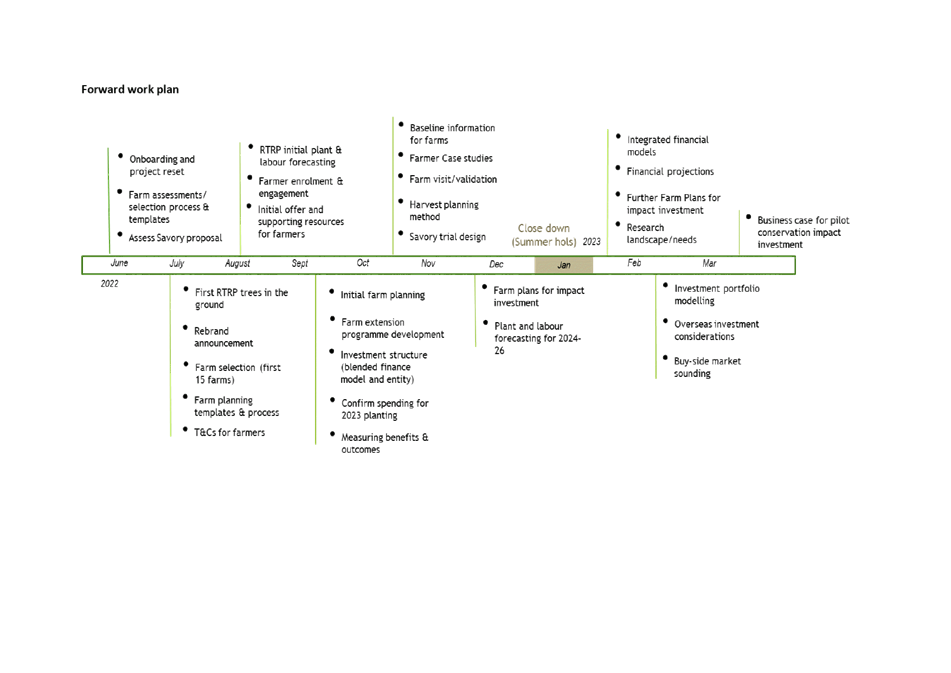

Forward

plan

55. With lead consultants

recruited and MPI now part of the project team, the expanded team has

recalibrated the forward direction for the project. An updated project roadmap

and milestone view was submitted to the project Steering Group in mid-June as

illustrated in

Attachment 1.

56. The main steps in the

forward work programme are summarised as follows:

56.1. July: Confirmation of farm

planning framework and prioritised farms

56.2. July: Comms survey results,

initial planting, project offer and project renaming

56.3. August: Farmer enrolment

for priority farms

56.4. September: Measuring

benefits and outcomes, reporting framework

56.5. September/October: Farmer

engagement, baseline information, pilot farm identification, develop 2023

planting requirements

56.6. November/December: Farmer

engagement, farm visits and farm/forestry plans

56.7. February: Finalise

remaining farm/forestry plans, develop forward planting programme

56.8. February: Integrated

financial modelling and forecasting

56.9. March: Investor sounding

56.10. April: Business case developed.

Decision Making Process

57. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision making

provisions do not apply.

Recommendation

That

the Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee receives and notes the Right

Tree Right Place: Year 1 report and Year 2 programme staff report.

Authored by:

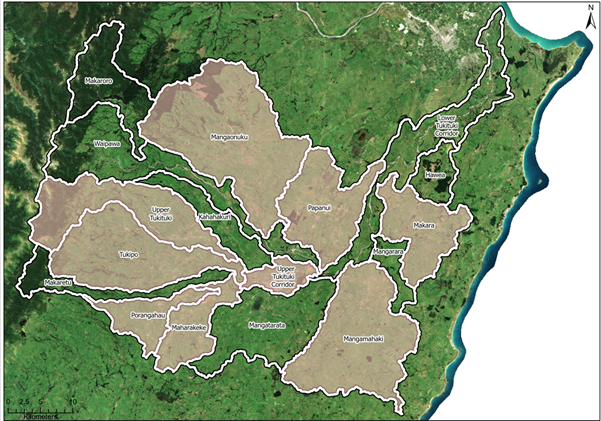

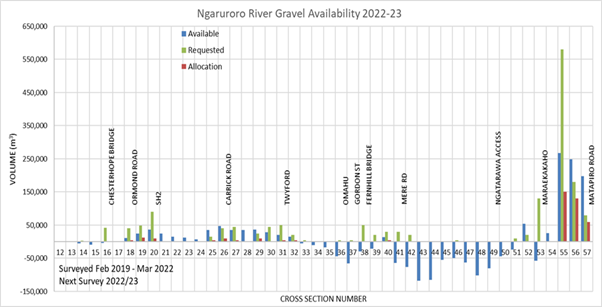

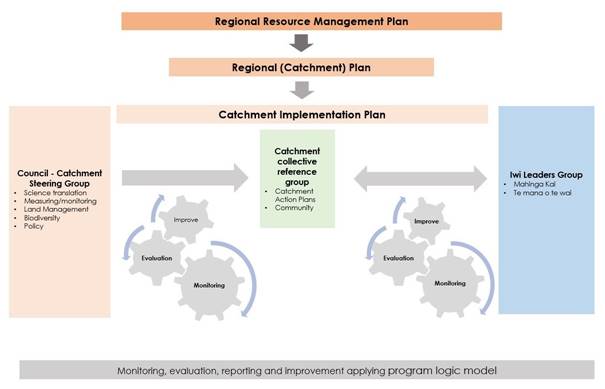

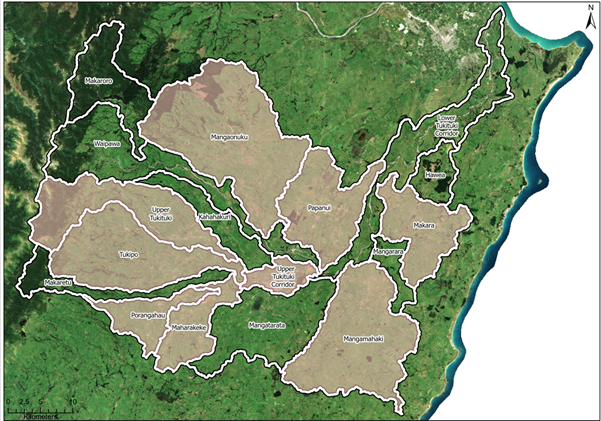

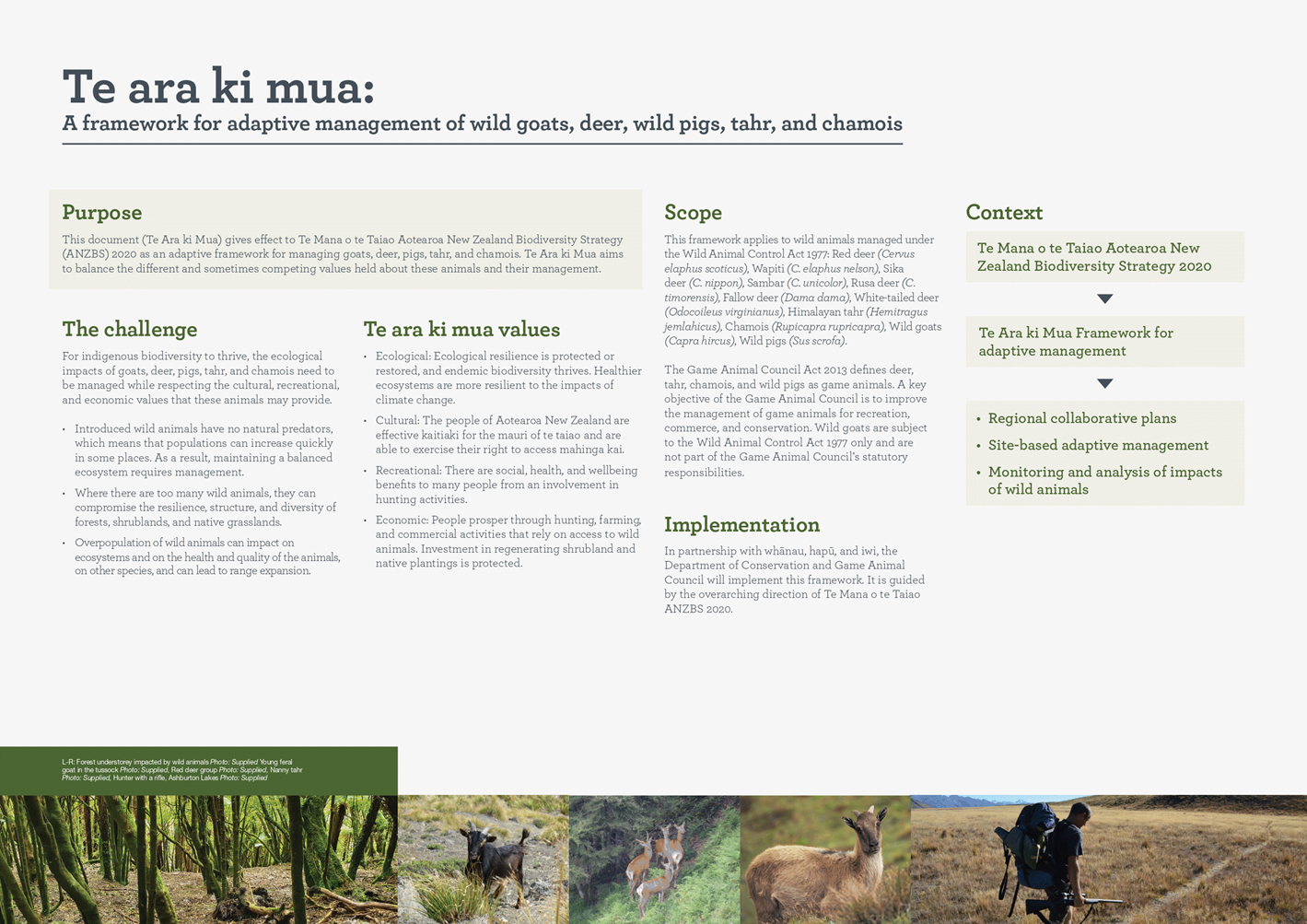

|