Extraordinary Meeting of the Hawke's Bay Regional

Council

Date: Wednesday 15 April 2020

Time: 9.00am

Agenda

Item Subject Page

1. Welcome/Apologies/Notices

2. Conflict

of Interest Declarations

3. Confirmation of

the Extraordinary Regional Council Meeting held on 8 April 2020

Decision Items

4. Regional Planning

Committee Tangata Whenua Representation on Council’s Committees 3

5. Implications of

Alert Level 3 on TANK Notification 5

Information or Performance

Monitoring

6. Climate Change

Working Group Update 11

7. Hawke’s Bay

Summer 2019-20 15

8. Select Committee

Report on the Resource Management Amendment Bill 27

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Wednesday 15 April 2020

SUBJECT: Regional Planning Committee Tangata

Whenua Representation on Council’s Committees

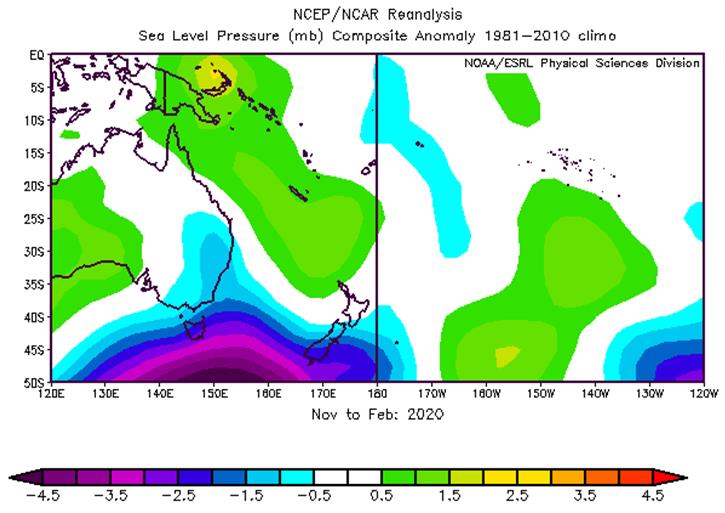

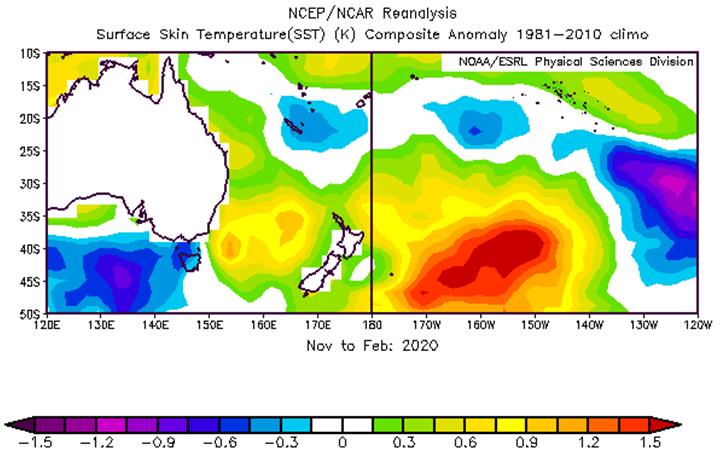

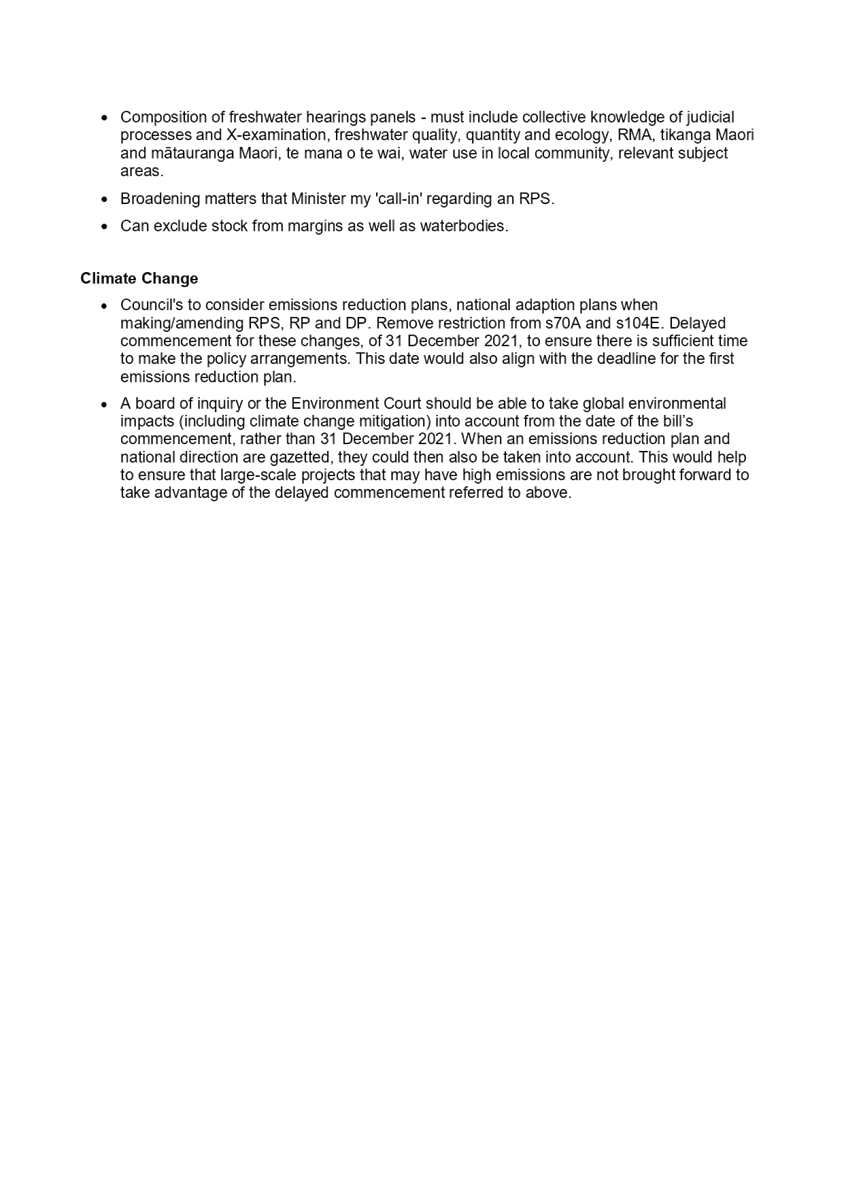

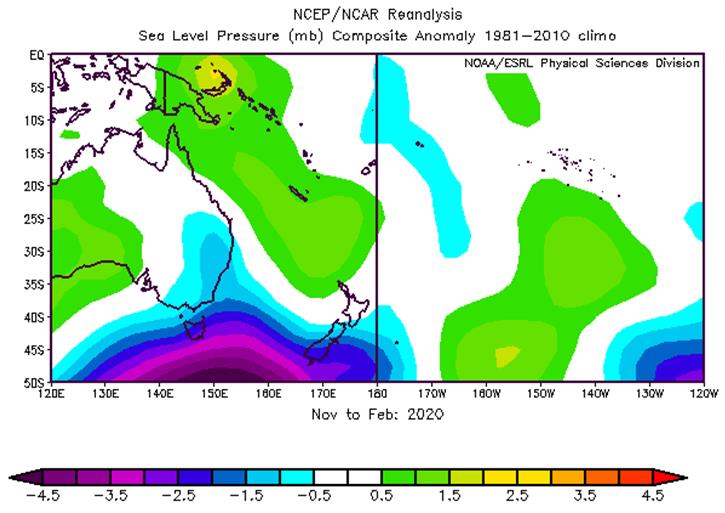

Reason for Report

1. This item provides the means for Council to

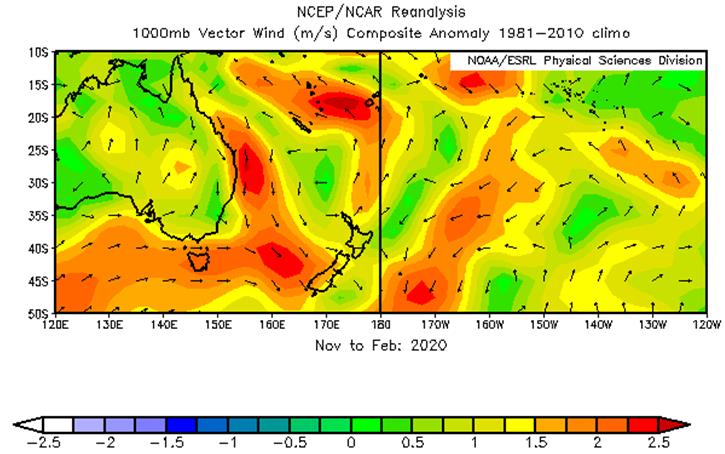

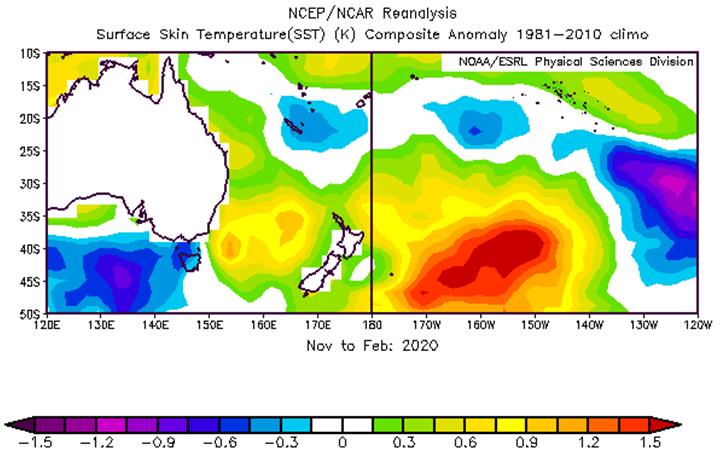

confirm Regional Planning Committee (RPC) tangata whenua representation on

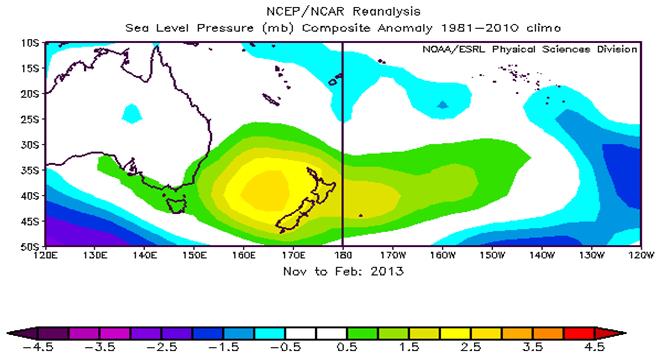

Council’s standing committees.

Background

2. Traditionally, the Regional Council has had tangata whenua

representatives of the RPC on:

2.1. the

Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee (1)

2.2. the Corporate

and Strategic Committee (1)

2.3. the Hearings

Committee (2 x RMA Making Good Decisions accredited).

3. In addition, the Environment and Integrated Catchments Committee has

requested tangata whenua representation from the RPC on

the Climate Change working party (2):

4. Tangata whenua representatives provide tangata whenua views and

contribute valuable input to the issues considered by those committees, as well

as provide feedback to the RPC on wider Council activities outside the scope of

the RPC RMA functions.

Regional Planning Committee

Nominations

5. The Tangata Whenua Hui on 17 March 2020 appointed Api Tapine as the

representative to all Council committees requiring representation from tangata

whenua members of the RPC.

6. At this stage the RPC has decided to nominate one member across all

of the committees. This is seen as a consistent move to ensure a seamless

reporting process from both Tangata Whenua and Council, and was confirmed with

Rex Graham and James Palmer at an 18 March meeting with the RPC Co-chair and

Deputy Co-chair.

Financial and

Resource Implications

7. The remuneration for tangata whenua representatives’

attendance at meetings other than the Regional Planning Committee is currently $400

per meeting plus associated travel costs, paid upon submission of a Travel

Claim form.

8. This is considered to be fair and reasonable and is the same

remuneration paid to Māori Committee representatives performing the same

roles. This per meeting remuneration is in addition to the remuneration paid

for the role of tangata whenua Regional Planning Committee member, currently $13,750 per annum.

9. This remuneration is within the budgets provided in the Māori

Partnerships cost centre.

Decision Making Process

10. Council

and its committees are required to make every decision in accordance with the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed

the requirements in relation to this item and have concluded:

10.1. The

decision does not significantly alter the service provision or affect a

strategic asset.

10.2. The use

of the special consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

10.3. The

decision is not significant under the criteria contained in Council’s

adopted Significance and Engagement Policy.

10.4. The

decision is not inconsistent with an existing policy or plan, and is within

Council’s purview in accordance with:

10.4.1. LGA

s81(1) A local authority must (a) establish and maintain processes to provide

opportunities for Māori to contribute to the decision-making processes of

the local authority, and

10.4.2. (b)

consider ways in which it may foster the development of Māori capacity to

contribute to the decision-making processes of the local authority.

10.5. Given

the nature and significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also

the persons likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions

made, Council can exercise its discretion and make a decision without

consulting directly with the community or others having an interest in

the decision.

|

Recommendations

That

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council:

1. Receives

and considers the “Regional Planning Committee Tangata Whenua

Representation on Council’s Committees” staff report.

2. Agrees

that the decisions to be made are not significant under the criteria

contained in Council’s adopted Significance and Engagement Policy, and

that Council can exercise its discretion and make decisions on this issue

without conferring directly with the community or persons likely to have an

interest in the decision.

3. Confirms

the appointment of Apiata Tapine as the Regional Planning Committee

representative on the:

3.1. Environment

and Integrated Catchments Committee

3.2. Corporate

and Strategic Committee

3.3. Hearings

Committee

3.4. Climate

Change working party

3.5. Regional

Council, with full speaking rights but no voting rights.

4. Confirms

that the remuneration to be paid for attendance at Regional Council and

Committee meetings is $400 per meeting plus associated travel cost

reimbursement, to be paid upon approval of an eligible Travel Claim Form

submitted by the tangata whenua representative.

|

Authored by:

|

Leeanne

Hooper

Governance Lead

|

|

Approved by:

|

Joanne

Lawrence

Group Manager Office of the Chief Executive

and Chair

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no

attachments for this report.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL

COUNCIL

Wednesday 15 April 2020

Subject: Implications of Alert

Level 3 on TANK Notification

Reason for Report

1. This item seeks

Council’s further consideration of the notification date for TANK Plan

Change 9, and a decision on whether to proceed to notify the plan change on 2

May.

Officers’ Recommendation(s)

2. Whilst there

has been no further national direction as to whether the Alert Level 4

restrictions will be extended, Council officers recommend that Council

considers whether the notification of TANK Plan Change 9 on 2 May 2020 is

appropriate.

3. Direction from

Council as to whether to notify the plan on the 2 May would enable staff to

initiate the consultation process, should this be considered the appropriate

approach. Staff have indicated that an appropriate lead-in period of two

weeks would ensure that the communications around notifying the TANK plan are

effective, and that the consultation process is fit for purpose given the

current restrictions.

Executive Summary

4. This paper

presents options to the Council for consideration for notifying the TANK plan,

being:

4.1. Agree to

proceed with notification on the 2 May, as agreed at the 25 March Council

meeting on the 25 March, with a 9 week submission period, or

4.2. Agree to

notify the Proposed TANK Plan two weeks following Hawke’s Bay being

reduced to Alert Level 3 within which staff will make a further recommendation

about the appropriate notification period and process, or

4.3. Agree to

delay notification of the TANK plan to an alternative and specified date.

Background/Discussion

5. The RPC and Regional Council resolved to notify the Proposed TANK

Plan Change 9 on 28 March. The Plan was to be notified on 28 March for a

period of 42 working days (to the end of May).

6. The Council received a paper at its meeting on the 25 March titled

‘TANK Notification Delay Options’. The paper highlighted that

national direction to manage the spread of COVID-19 had intensified and that

this would have a significant impact on the community. The governments

restrictions would materially impact how people could interact and the level

and quality of the engagement during this notification process.

7. Three options for notification were presented to the Council.

8. The Council resolved to defer notification of the Proposed TANK Plan

Change to the 2 May 2020 with a 9 week submission period because of the impact

of the COVID -19 management. Given the unknown nature of the COVID-19 pandemic

on the region it was also agreed that this date was subject to confirmation by

Council closer to 2 May.

9. Whilst there has been no further direction at a national level as to

whether the ‘lock-down’ will be extended or not, it is appropriate

for Council to consider what implications may arise should the Alert Level be

scaled back from Alert Level 4 to Alert Level 3, in particular on the

notification of the TANK plan, the impacts of this on the community, and to

consider whether the notification of the Plan on the 2 May is still appropriate

.

10. It should be noted that a

number of assumptions have been made in preparing this paper. Staff have relied

on the best information to hand at the time the paper was written.

Options Assessment

11. At present the Level 4

‘lock-down’ is scheduled to cease as of midnight Wednesday

22 April, the assumption being that the Alert Level would reduce to Level

3 as opposed to being lifted entirely.

12. A lifting of restrictions

will enable some level of more nuanced engagement, particularly with iwi, where

kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face) communication is valued. However there will

still be significant changes to how we manage this process. As noted in

the paper to Council on the 25 March the communication plan has been amended to

adopt a new style of engagement, in practical terms, this would enable staff to

notify the plan on the 2 May and utilise non-contact engagement measures,

including virtual meetings and social media.

13. At Alert Level 3 the

following restrictions, as set by Government, would be expected to be adhered

to.

14. The critical limitations

of this Alert Level to notifying the TANK plan would be the restrictions on

mass gatherings, closure of public venues and alternative ways of working.

Mass gatherings and closure of public venues

15. Mass gatherings were

initially considered to be a group of 500 people, however this was later reduced

to a group of 100 or more. Whilst there would be alternative non-contact

engagement methods available it could affect the ability of people to debate

the plan provisions and enable them to prepare fully informed submissions.

16. A further consideration

would be the perceived risk associated with hui, meetings and face to face

consultation. There is likely to be general reluctance from tāngata

whenua and the community to meet in large groups, as the fear of outbreak and

risk associated with face to face meetings has the potential to be high.

Alternative Ways of Working

17. Whilst it is evident that

there is a high percentage of the workforce remaining in active employment

during this Level 4 period the style of working has changed

significantly. This trend of working from home and in isolation can be

expected to continue for many businesses and organisations at Alert Level 3.

18. There has been greater

demands and pressures placed on the primary sector arising from alternative

ways of working. They are being challenged with staffing issues with social

distancing and displacement of the migrant workforce.

19. HBRC

staff can engage with many of the relevant stakeholders who continue to work

from home. Engagement with the wider public may be less effective than

‘normal’ as there are fewer opportunities for meetings and there

would be greater reliance on social and other on-line media. The way we need to

work in the COVID-19 environment has meant a huge disruption, and we are still

coming to terms with that. But ways of communication are still developing and

the options available to us for virtual communications is changing rapidly and

becoming the ‘new normal’ for most.

20. That being said,

alternative ways of working does have implications on the TANK notification and

consultation in that those within the primary sector particularly (who are most

likely to be impacted by the plan) may not be able to engage at a level that

they would like under normal circumstances. This is likely to also be the case

for other sectors of the community. It can be anticipated that all

essential services will continue to be under pressures and constraints, with

the delivery of essential services remaining a priority.

Considerations of Tangata Whenua

21. As noted at the previous

Council meeting Alert Level 3 restriction would still have an impact on the

ability for tāngata whenua to discuss and debate the content of the TANK

plan. Māori traditionally discuss such important matter kanohi ki te

kanohi (face to face). It is unclear whether hui could be held at marae

(further clarification needs to be sought to determine whether marae would be

considered a public venue). As with any mass gathering the numbers would be

restricted to less than 100 people, should it be permissible to hold hui at

marae.

Other

Considerations

22. There are a number of

other factors to consider when determining whether it remains appropriate for

the TANK plan to be notified on 2 May. Primarily it is the huge

disruption caused by this lockdown on the social and economic well-being of the

community.

22.1. The impact of the

COVID-19 lockdown on businesses has been significant, is variable across the

different sectors and will be on-going for an indeterminate length of

time. It impacts are felt not only in the short-term and on this

notification step of the Plan Change process, but the plan's content is also

likely to impact somewhat differently than modelled. Progressing with the

TANK plan change will be challenging, but provides an element of ‘normality’

- providing a future and gives support to the reality that life is still going

on.

22.2. There has been no

significant shift from government with regards to the planned work programme

for Essential Freshwater and we anticipate that this will still be delivered

later this year. It is unclear what form this will take in response to COVID-19

impacts, or what this will mean for the region. These are unprecedented times

and the ramifications of COVID-19 on our community and economy are unknown.

22.3. There has been mention

within the media that we should brace ourselves for a ‘second wave’

of the virus (the suggestion is this could hit around August in the ‘flu

season’). If this were the case then there is an argument that we

should look to progress the plan (and other ‘business as usual’) as

much as possible. We are already facing a highly changing state and to

further delay progress is not helpful in the longer term. There is security in

progressing the TANK plan for consent holders and water users. Longer submission

periods and more technology based consultation/engagement methods will help

with the adjustments necessary.

22.4. HBRC staff resources

have largely been diverted to Civil Defence Emergency Management during these

first few weeks of COVID-19 response. It cannot be assumed that the CDEM

demands will be scaled back if there is on-going impact from COVID-19

management. The diversion of staff resources from business as usual will

need to be carefully managed. Should Council determine that the plan should

be notified on 2 May some staff would not be available to then be re-deployed

to CDEM duties. It should be noted that from the Policy and Planning

notification of the TANK Plan would require one FTE and partial support

staffing from the Marketing and Communications team.

22.5. Staff previously

suggested an increase of the submission period to 9 weeks which was approved by

Council. If the future is more challenging than we anticipate then there

is an option to extend that submission period if necessary (for example the

Environment Court has recently allowed for an extension for appeals on the

Marlborough Plan as a result of COVID-19 management).

22.6. Council may be seen as

‘blinkered’ or insensitive if it does not adequately account for

the impact of COVID-19 management on communities and businesses. Whilst

not as dramatically impacted by drought and TB as Central Hawke’s Bay we

need to be cognisant of the effects these events are having on the wider rural

community, in addition to the impact of COVID-19. There are high levels

of stress and anxiety within the community that needs to be managed

sensitively. Whilst no direct research has been undertaken to determine

what impact notification of the TANK plan would have on the rural community it

is something that the Council should be mindful of.

22.7. At present the

identification of those who are considered “essential services”

dictates who can get out. This may be re-defined at Alert Level 3,

however the assumption is that those who are essential workers are unlikely to

be less busy as a consequence of the Alert Level being scaled down.

23. If the Council were to

persist with notification of the TANK plan on 2 May there remains the option to

reconsider this closer to the date, either at one of the weekly Council

meetings while we are still at Alert Level 4 or at the next regular Council

meeting scheduled for 29 April.

24. Three options are

presented to the Council within the recommendations below, these are:

24.1. Agree to proceed

with notification on 2 May, as agreed at the Council meeting on 25 March, with

a 9 week submission period, or

25. Agree to

notify the Proposed TANK Plan two weeks following Hawke’s Bay being

reduced to Alert Level 3 within which staff will make a further recommendation

about the appropriate notification period and process; or

26. Agree to

delay notification of the TANK plan to an alternative and specified date.

27. Given that the date for

the moving to Alert Level 3 is uncertain the second option has been provided to

accommodate this uncertainty, this still allows a two week lead in for staff to

undertake final preparations for the communications.

28. On the assumption that

Council proceed with notification on 2 May and no alternative date is suggested

in the interim then the TANK plan notification process will resume. The

communications and engagement plan will be initiated as amended in response to

COVID-19.

Financial and Resource Implications

29. There have been some

financial implications for the deferral of notifying the TANK plan, in terms of

amending dates on communications and publications, however these are considered

to be reasonably insignificant given the wider economic impact of COVID-19 on

the community.

30. As noted above there are

staff resourcing considerations should Council proceed with TANK notification,

as this resource would be temporarily diverted from CDEM functions.

Decision Making

Process

31. Council

and its committees are required to make every decision in accordance with the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed

the requirements in relation to this item and have concluded:

31.1. The

decision does not significantly alter the service provision or affect a

strategic asset.

31.2. The use

of the special consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

31.3. The

decision is not significant under the criteria contained in Council’s

adopted Significance and Engagement Policy.

31.4. The

decision is not inconsistent with an existing policy or plan.

31.5. Given

the nature and significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also

the persons likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions

made, Council can exercise its discretion and make a decision without

consulting directly with the community or others having an interest in

the decision.

|

Recommendations

That

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council:

1. Receives and considers the “Implications of Alert Level 3 on

TANK Notification” staff report.

2. Agrees to:

2.1 proceed with notification on 2 May 2020, as agreed at the 25 March

2020 Council meeting, with a 9 week submission period

OR

2.2 notify the Proposed TANK Plan two weeks following Hawke’s

Bay being reduced to Alert Level 3 at which time staff will make a further

recommendation about the appropriate notification period and process

OR

2.3 delay

notification of the TANK plan to an alternative and specified date.

|

Authored by:

|

Ceri Edmonds

Manager Policy and Planning

|

Mary-Anne

Baker

Senior Planner

|

Approved by:

|

Tom Skerman

Group Manager

Strategic Planning

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no

attachments for this report.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Wednesday 15 April 2020

Subject: Climate Change Working

Group Update

Reason for Report

1. This report provides a brief report back on preliminary discussions

amongst the climate change working group.

Executive Summary

2. The Working Group has met on one occasion to date (16 March).

Discussions traversed a range of matters. There are two key dimensions to

the work – adaptation to, and mitigation of, climate change.

Both are essential. There are also two key focus areas:

2.1. Hawke’s Bay Regional Council as an organisation; and

2.2. Hawke’s Bay as a region.

3. The working group has prioritised several matters that warrant

progress sooner rather than later, bearing in mind the modest budgets currently

available for work in the 2020-21 financial year. But importantly, these

matters were prioritised before the COVID-19 lockdown period.

4. Due to staffing commitments to the COVID-19 and drought response

effort, the pace of progress on this project has slowed considerably since the

working group’s initial meeting.

Background

5. At its meeting on 5 February 2020, the Committee had agreed to form

an interim climate change working group. The working group is to assist

staff in shaping a regionally coordinated programme for responding to climate

change. Councillors Rick Barker, Hinewai Ormsby and Martin Williams are

group members. The Māori Committee had nominated Michelle McIllroy and Dr Roger Maaka to

join the group. After the working group’s first meeting,

tāngata whenua members of the Regional Planning Committee nominated Apiata

Tapine to also join the group.

6. The working group met with key HBRC staff on Monday, 16 March for a

semi-structured discussion on relative priorities and other suggestions arising

from the Committee’s discussions in February.

Discussion

7. The working group’s preliminary discussions focused on two

areas:

7.1. HBRC as an organisation undertaking corporate business activities

and activities relating to mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change

7.2. Hawke’s Bay as a region, with wide ranging community interests

and capabilities to take action responding to climate change.

HBRC as an

organisation

8. As an organisation, HBRC must lead by good example and continue to

drive reductions in its own direct emissions, energy consumption, and waste

etc.

9. Further to that, we should begin with a ‘stocktake’ of

existing and planned actions as to both adaptation and mitigation.

Earlier staff briefing papers to this Committee have documented several

iterations of the actions HBRC has underway or planned that directly and

indirectly relate to climate change.

10. From there,

evaluate ’gaps’ in HBRC’s actions compared to other

regions. This can help build a more complete picture of potential

initiatives and their relative cost-effectiveness. The stocktake and gap

assessment can be completed by staff.

11. In

parallel to that work, we would complete a fulsome assessment of HBRC’s

own carbon footprint. That would provide us with better understanding of

HBRC’s current baseline and to target further ongoing improvements in its

own corporate operations such as energy use, waste reduction, travel and

procurement policies. A comprehensive carbon footprint assessment requires

specialist external consultants.

12. While we

may aspire to do lots of things with many other agencies and groups, limited

budgets for remainder of 2019-20 and 2020-21 financial years pose tight fiscal

constraints. Nevertheless, we will look for opportunities with partner agencies

to leverage co-resourcing of some initiatives where relevant.

13. The

2021-31 LTP presents an opportunity to further boost priority and associated

resourcing of a regionally coordinated programme of climate change response

actions. In the meantime, our focus ought to be on developing community

awareness and changing behaviours through various media, publicity and

communication-related initiatives.

Hawke’s Bay as a region

14. At a

regional level, we need to understand our region’s current carbon

emissions profile if we are serious about a time bound net carbon zero

target. A regional inventory of the emissions profile will paint a

‘snapshot’ picture of where we are today, so we’re better

informed of pathways to our region becoming carbon neutral in a few

decades. This is key to understanding the policy priorities and settings

for any interventions and support. Based on similar inventories done by

other regions, this work can be done by specialist consultants (estimates are

around $50,000).

15. Commissioning

a climate change community perceptions survey (phone/mail/digital) will also

provide insights beyond what was the 2019 HBRC Residents Perception Survey.

16. HBRC

alone cannot ‘fix’ climate change or make our region

carbon-neutral. HBRC must lead work with others to strengthen local

community messages about efforts to mitigate human-induced effects of climate

change. There are already a variety of agencies, organisations and

businesses doing really valuable work showing what can be done. To this

end, a number of suggestions were made during the working group’s meeting

about communications and messaging for community engagement so HBRC does not

duplicate others’ work.

Preliminary Priorities

17. The

following are three of the ‘big ticket item’ priorities for 2020

arising from the working group’s initial discussion. These are

being presented to the Committee for information update purposes at this time.

17.1. Build a

‘stocktake’ of existing and planned actions as to both adaptation

and mitigation, then a ’gaps’ assessment of those actions compared

to other regions

17.2. Undertake

a regional inventory of greenhouse gas emissions in Hawke’s Bay[1]

as a present day ‘snapshot,’ yet repeatable at regular intervals in

future years

17.3. Undertake

a community survey of HB residents’ climate change perceptions etc.

18. The three

big-ticket priorities for 2020 above can be readily augmented by a variety of

smaller-scale initiatives which can be progressed within existing staff

capacity. Some examples of these include:

18.1. refreshing

webpage content

18.2. developing

a collection of short videos profiling examples of what individuals can do

themselves to reduce their own carbon footprints

18.3. developing

closer ties with other councils in the region to better align climate

change-related actions and activities

18.4. further

reducing energy use and waste disposal across HBRC’s buildings and facilities.

COVID-19 and next steps

19. COVID-19

poses some challenges for immediate term and an indefinite time period.

For example, limits on public gatherings, meetings, workshops, conferences etc.

20. COVID-19

is disrupting many of the day-to-day activities of businesses and people.

Commissioning new research work, developing digital tools, media packs or

making general contact with people is no longer simply as it used to be.

21. COVID-19

also presents some opportunities for lessons and behaviours to transfer across

to climate change response, e.g. increased use of virtual meetings in lieu of

travel for in-person meetings. This may also be a good time to develop

the stocktake, inventory and preliminary thinking on the future policy options

ahead of 2021-31 LTP preparation. However, many of the project’s

key staff are likely to continue assisting with the CDEM Group’s response

to the COVID19 and drought. That ongoing involvement will certainly

influence the pace and degree of progress that key staff can make on this

project over at least the April/May period.

Decision Making

Process

22. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision making

provisions do not apply.

|

Recommendation

That Hawke’s Bay Regional Council

receives and notes the “Climate Change Working Group Update”

report.

|

Authored by:

|

Gavin Ide

Principal

Advisor Strategic Planning

|

|

Approved by:

|

Tom Skerman

Group Manager

Strategic Planning

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no

attachments for this report.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL

COUNCIL

Wednesday 15 April 2020

Subject: Hawke’s Bay

Summer 2019-20

Reason for

Report

1. Drought conditions developed in Hawke’s Bay and across the

North Island during summer 2019-20, leading to the declaration of a

“large scale adverse event” by the Agriculture Minister Damien

O’Connor on 12 March 2020. This paper places the rainfall, river

flows, groundwater levels and soil moisture levels of summer 2019-20 in an

historical context and describes how the dry conditions evolved.

Executive Summary

2. Hawke’s Bay had below normal rainfall, above average

temperatures and relatively high rates of potential evapotranspiration from

November 2019 to February 2020. In comparison to the 2012-13 drought, the

lack of rainfall in 2019-20 was not as evenly felt across the region or in

places as severe. However, areas that were worse affected were the

Ruahine Range, Ruataniwha Plains and Southern Hawke’s Bay.

3. River flows have generally tracked below normal this summer.

Northern parts of Hawke’s Bay did not experience extreme low flows.

Ngaruroro River experienced levels comparable to the 2012-13 drought. The

Tukituki River recorded the lowest mean flows on record.

4. This pattern was reflected in the groundwater levels, with the

Ruataniwha basin (in the Tukituki catchment) having the highest proportion of

monitoring wells at their lowest recorded water levels.

5. The weather pattern in 2019-20 featured higher than normal mean sea

level pressure to the northwest and east of New Zealand and lower than normal

pressure to the southwest. A relatively deep, warm and stable layer of

air over the North Island meant that active systems approaching from the

southwest weakened as they moved north. Above average sea temperatures

contributed to the hot weather and high evaporation rates.

6. The El Niño-Southern

Oscillation was in a neutral phase through summer and is expected to remain

that way through the coming autumn and winter. The pattern of weather

predicted by the seasonal models in past months does not appear to change

significantly in the months ahead. Near normal mean sea level pressure

and rainfall and above average temperatures was the common forecast for summer

and the models continue with that prediction for the coming few months.

Background

7. Prior to summer 2019-20, the most recent drought experienced in

Hawke’s Bay was in the summer of 2012-13. The 2012-13 drought

affected much of the North Island and was declared a medium scale adverse event

on 15 March 2013 by the Minister for Primary Industries. With respect to

different parts of Hawke’s Bay, NIWA assessed the 2012-13 drought as

either the worst in 40 years or second only to 1997-98. The summer

weather was dominated by “blocking” high pressure systems which

prevented rain-bearing fronts from moving over New Zealand1.

8. Following the 2012-13 drought, NIWA developed a New Zealand Drought

Index (NZDI) based on four common indices of climatological drought. Throughout

summer 2019-20 the NZDI typically categorised Hawke’s Bay as very dry or

extremely dry, with parts of the region in drought or severe drought.

Drought or severe drought levels were largely along the western ranges,

particularly the Ruahine Range and adjacent hill country and surrounds.

Discussion

Rainfall and Potential

Evapotranspiration

9. The 2019-20 drought began its development in November and followed a

wetter than average early spring. November was not only a month of below

normal rainfall, but temperatures were very hot. Daytime temperatures

reached 3°C above the

monthly average and the average potential evapotranspiration (PET) rate for the

month was the highest recorded on the Ruataniwha Plains for November since

monitoring began in 2007. PET is the amount of moisture that would be

lost by evaporation and transpiration from a reference crop, such as grassland,

if sufficient moisture is available.

10. Both

December and January had below normal rainfall and temperatures between 0.5 -1°C warmer than average. The dry

conditions that developed during late spring and into summer rapidly worsened

in February when all, but northern areas of the region received approximately

10% of normal February rainfall. Temperatures were again very hot and

reached 3°C above the

February average, resulting in high but not record rates of PET.

11. Table 1 shows the percentage of average rainfall received in

different parts of the region from November to February inclusive and compares

it to 2012-13. Most of the region shared similar and more severe levels

of below normal rainfall in 2012-13 than in 2019-20 except for the Ruahine

Range, the Ruataniwha Plains and Southern Hawke’s Bay.

|

Area

|

2012-13 % Average Nov-Feb Rainfall

|

2019-20 % Average Nov-Feb Rainfall

|

|

Waikaremoana

|

53

|

71

|

|

Northern

Hawke’s Bay

|

59

|

64

|

|

Tangoio

|

52

|

52

|

|

Kaweka

|

50

|

53

|

|

Ruahine

|

64

|

39

|

|

Heretaunga Plains

|

34

|

42

|

|

Ruataniwha

Plains

|

53

|

41

|

|

Southern

Hawke’s Bay

|

52

|

42

|

|

Hawke’s Bay

Region

|

51

|

51

|

Table 1: November to February rainfall totals for 2012-13 and

2019-20 for different parts of Hawke’s Bay as a percentage of average

November to February rainfall totals. Areas where the dry conditions appear

worse in 2019-20 than in 2012-13 are highlighted in red.

12. The November to February rainfall totals in the Ruahine Range and

Ongaonga were the lowest recorded in the past 50-60 years, surpassing those of

1997-98 and 2012-13.

13. Much of

Hawke’s Bay is considered “summer dry”, i.e. PET exceeds the

amount of rainfall typically received. The difference between rainfall and PET

can be used to gauge the magnitude of dry conditions. Figure 1 shows cumulative

rainfall minus cumulative PET for the hydrological year (July to June) at the

Ongaonga Climate site and includes average conditions as well as the 2019-20 and

2012-13 levels. The graph indicates a greater moisture deficit than

average for most of the period and greater than that of 2012-13. This is

not the case at Bridge Pa on the Heretaunga Plains (Figure 2), where early

spring rainfall raised 2019-20 above both average levels and those of 2012-13,

before dipping below average in February.

Figure 1: A comparison of average, 2012-13 and 2019-20 levels

of cumulative rainfall – PET at Ongaonga Climate station over the

hydrological year. Data for 2019-20 is shown up until late March 2020.

Figure 1: A comparison of average, 2012-13 and 2019-20 levels

of cumulative rainfall – PET at Ongaonga Climate station over the

hydrological year. Data for 2019-20 is shown up until late March 2020.

Figure 2: A comparison of average, 2012-13 and 2019-20 levels

of cumulative rainfall – PET at Bridge Pa Climate station over the

hydrological year. Data for 2019-20 is shown up until late March 2020.

Figure 2: A comparison of average, 2012-13 and 2019-20 levels

of cumulative rainfall – PET at Bridge Pa Climate station over the

hydrological year. Data for 2019-20 is shown up until late March 2020.

Soil moisture

14. The lack

of rainfall and high rates of PET from November to February resulted in soil

moisture levels tracking below normal, apart from northern areas where soil

moisture followed median levels. For many areas, such as around and south

of the Heretaunga Plains and also to the north up to Taharua, soil moisture

levels at times dropped into the lowest 10% of readings at individual sites.

Levels were comparable to 2012-13 for much of summer, especially on the

Ruataniwha Plains where the onset of dry conditions mirrored that of 2012-13

(Figure 3). Elsewhere the onset tended to be delayed by a month by the

early spring rain.

Figure

3: Soil moisture levels at

Ongaonga Climate Station for 2019-20 compared to median levels and

2012-13. Data for 2019-20 is shown up until late March.

River Flows

15. With

below normal rainfall in November, river flows began dropping across the Hawkes

Bay. The dry, hot summer resulted in average river flows below 25% of their

long-term average, particularly in the southern Hawke’s Bay. In

comparison, 2018-19 was within 75% of the long-term average river flow.

16. In the Northern

Hawke’s Bay, river flows have been below 50% of their long-term

average. However, river levels have remained above those seen in the dry

season of 2012-13. Hangaroa River dropped throughout the summer months, but has

seen a rise in its average level in March due to rain in northern Hawke’s

Bay during this period. The Esk River has steadily dropped below

the normal range through the summer months, reflecting similar river levels to

2012-13. River levels from February to March saw very little change.

17. The Ngaruroro

River dropped below the normal flow range from December onwards, declining

significantly through the summer months. February average river levels were the

lowest for the month on record (1980-2020). Current data for March shows

river levels have remained steady with no further decreases.

Figure 4: River flow levels at Ngaruroro – Fernhill for

2019-20 compared to river levels of 2018-19 and 2012-13. Data for 2019-20 is

analysed up until late March.

18. Central

Hawke’s Bay river levels have been below 25%

of the long-term average from November onwards. The Tukituki River

dropped to below normal in November to similar drought levels of

2012-2013. River levels continued to drop in the following months with

December-March mean flows the lowest on record. However, flow recession has

levelled off in March, with the dry season coming to an end.

Figure 5: River flow levels at Tukituki – Red

Bridge for 2019-20 compared to river levels of 2018-19 and 2012-13. Data for

2019-20 is analysed up until late March.

19. Despite

the lower average river flows recorded for 2019-20, compared to 2012-13, the

7-day mean minimum flows recorded are comparable with those recorded in 2012-13

(Table 2). Minimum flows of the Ngaruroro and Tukituki have been similar to

those recorded in the 2012-13 drought period and are considerably lower than

the 2018-19 minimum flow records.

|

River

|

2012-13 Minimum River Flow (l/s)

|

2018-19 Minimum River Flow (l/s)

|

2019-20 Minimum River Flow (l/s)

|

|

Northern Hawkes Bay

– Hangaroa River

|

284

|

866

|

594

|

|

Esk Central Coast

– Esk River

|

1669

|

2918

|

1816

|

|

Heretaunga Plains

– Ngaruroro River

|

1330

|

7089

|

1514

|

|

Central Hawkes Bay

– Tukituki River

|

2888

|

7003

|

2774

|

Table 2: Minimum river flows (7-day mean, L/s) so far this

year at key sites across the Hawke’s Bay region for the hydrologic years;

2012-13, 2018-19, and 2019-20.

Groundwater

20. Groundwater

levels began their normal seasonal decline in late October and early November

2019. Early spring rainfall, coupled with increased river flows, provided much

needed recharge to the Heretaunga and Ruataniwha Plains aquifer systems.

This caused groundwater levels to measure near normal for November and

December. Since December, below normal conditions became increasingly

more prevalent in addition to an increasing number of wells measuring lowest

ever monthly measurements.

21. Groundwater

level conditions for March measured below normal with only 5 wells out of 50,

measuring normal or above for the Heretaunga and Ruataniwha Plains (see pie

chart following).

22. On the

Ruataniwha Plains, over 60% of wells measured their lowest-ever levels for

March. Here, the less transmissive aquifers, with lower storage

properties, experience deeper drawdown impacts and slower recovery in response

to water use. In contrast, on the Heretaunga Plains, aquifers are highly

transmissive with strong surface-water connections resulting in shallow and

widespread drawdown impacts despite an overall greater volume of pumping than

in the Ruataniwha.

Figure

6: Groundwater level

conditions for March in the Heretaunga and Ruataniwha Plains. Note: Numbers

within the maps represent years of monitoring. Sites less than 5 years are

excluded from the analysis.

23. In

Ongaonga, groundwater levels are at their lowest-recorded (monitoring started

2004) and measured 42cm lower than the previous annual minimum measured in

January 2017. Telemetered data from our new multi-level wells for the Ongaonga

and Tikokino indicates groundwater levels in the shallow system are still

declining. In the deeper bores, there are indications groundwater levels maybe

beginning their normal seasonal rise back toward winter levels. On the

Heretaunga Plains, telemetered groundwater levels indicate groundwater levels

are beginning to recover.

Figure

7: Telemetry from the Ongaonga

wells. Black line represent the shallow well (30m) and the blue line represents

the deeper system (90m).

24. The

conditions experienced this summer have been, for many wells, the most extreme

on record. This means that at many wells’ (but not all) groundwater

levels are lower than the water levels measured in 2012-2013. The plot below

shows that a larger proportion of wells experienced the lowest recorded water

levels in 2020, and represents about 20% of the number of our monitoring

network.

Figure

8: The number of wells

experiencing the lowest water levels recorded, expressed as a percent of the

total number of wells monitored that year.

Weather pattern

25. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a

broad-scale climate mode known to influence Hawke’s Bay’s weather1.

The El Niño and La Niña phases are typically associated

with higher and lower risk respectively of a dry Hawke’s Bay

summer. Neither of these phases were in place for recent droughts and

instead neutral ENSO conditions existed for both the 2012-13 and 2019-20

droughts.

26. Another

climate mode that can play a role in the region’s spring weather is the

Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). Positive IOD events increase the probability of a

drier than normal Hawke’s Bay spring2. The IOD was strongly

positive during spring 2019 and although the season had a very wet start, the

event may have contributed to the onset of dry conditions in late spring and

into summer.

27. The

Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is another climate driver of New Zealand’s

weather. The SAM index refers to the north-south movement of the mid to high

latitude westerly wind belt of the southern hemisphere. During a negative SAM

the belt shifts north and westerlies increase over New Zealand while lighter

winds and anticyclones are expected in the positive mode. Average monthly

values of SAM were mostly negative during the four months, especially during

November and December.

28. Dominant

weather features during the four months of dry conditions included the presence

of higher than average mean sea level pressure (MSLP) in a zone extending

northwest of New Zealand and to the east (Figure 9). Ridging was also evident

in the upper atmosphere indicating a depth of warm, stable air. Lower than

average MSLP occurred to the southwest of the country and over the lower South

Island. Sea surface temperatures were above average around New Zealand

and significantly higher than normal in an area to the east of New Zealand

(Figure 10).

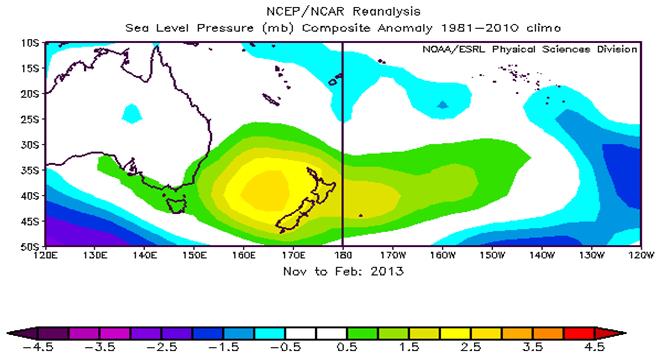

Figure

9: Mean sea level pressure

anomalies (mb) for November to February 2019-20 inclusive (NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis

using the1981-2010 climatology).

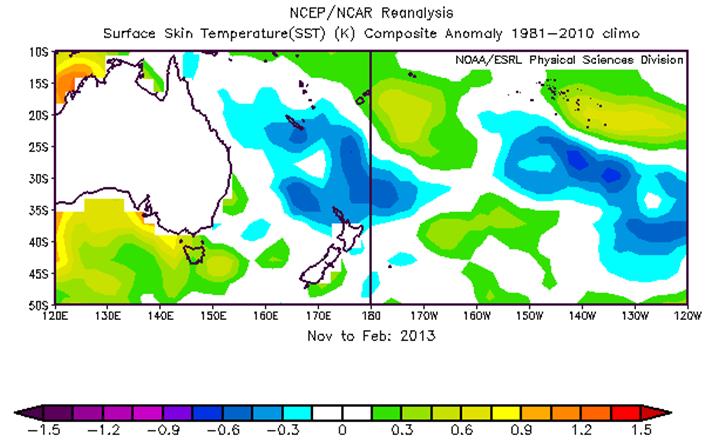

Figure

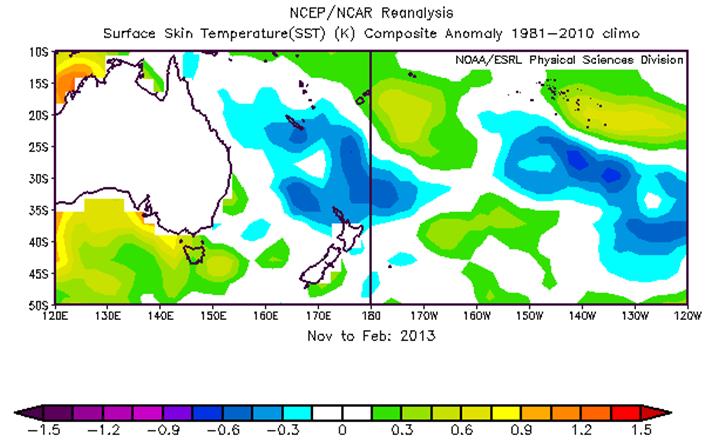

10: Sea surface temperature

anomalies (degrees Kelvin) for November to February 2019-20 inclusive

(NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis using the1981-2010 climatology).

29. The

anticyclones and an upper level ridge, extending from east of New Zealand to

the northwest, meant active fronts struggled to make progress over the North

Island as they moved onto the country from the low pressure systems to the

southwest. More often than not, the fronts weakened considerably as they

moved north and delivered very little rain to Hawke’s Bay and many parts

of the North Island.

30. The sea

level pressure pattern and predominantly negative SAM lead to a westerly wind

anomaly over Hawke’s Bay for the four month period (Figure 11). Tropical

cyclones tended to track east of New Zealand or down the western Tasman Sea as

they moved southward. The warm sea surface temperatures around and to the east

of New Zealand contributed to the warm summer temperatures that were

experienced. All of these factors produced a scenario of low rainfall and high

rates of PET that particularly affected the southwestern ranges of the region.

Figure

11: Vector wind anomaly (m/s)

for November to February 2019-20 inclusive (NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis using

the1981-2010 climatology).

31. The

pattern of weather observed in 2019-20 was different to that in 2012-13.

In 2012 /13, higher than normal pressure extended across all of New

Zealand and the Tasman Sea (Figure 12). Sea temperatures around the North

Island were cooler than in 2019-20 (Figure 13). The dominance of

anticyclones brought a prevalence of fine days to much of the country and the

cooler sea temperatures reduced the moisture holding capacity of weather

systems.

Figure

12: Mean sea level pressure

anomalies (mb) for November to February 2012-13 inclusive (NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis

using the1981-2010 climatology).

Figure

13: Sea surface temperature

anomalies (degrees Kelvin) for November to February 2012-13 inclusive

(NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis using the1981-2010 climatology).

Outlook

32. ENSO

neutral conditions are expected to persist through autumn and winter and

possibly into spring.

33. The

tropical cyclone season continues until the end of April. Therefore a small

window remains for an ex-tropical cyclone to reach New Zealand’s shores

and make a significant difference to drought affected areas.

34. Seasonal

forecast models typically predicted near normal mean sea level pressure, near

normal rainfall and above average temperatures for summer. Their outlook for

the next few months has similar predictions and a relatively unchanged weather

pattern.

1Porteous, A. and Mullan, B., 2013. The 2012-13 drought: an assessment

and historical perspective. NIWA Client Report No. WLG2013-27.

2Fedaeff, N. and Fauchereau, N. 2015. Relationship between Climate

Modes and Hawke’s Bay Seasonal Rainfall and Temperature. NIWA

Client Report No. AKL2015-016.

Next

Steps

35. An update

is expected to be provided if this paper is presented to Council, to provide

recent information if the situation has changed since this report was

finalised.

Decision Making Process

36. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision making

provisions do not apply.

|

Recommendation

That Hawke’s Bay Regional Council

receives and notes the “Hawke’s Bay

Summer 2019-20” staff report.

|

Authored by:

|

Simon Harper

Senior Scientist

|

Dr Kathleen

Kozyniak

Principal Scientist (Air)

|

|

Dr Jeff Smith

Manager Scientist

|

Thomas

Wilding

Team Leader Hydrology Hydrogeology

|

Approved by:

|

Iain Maxwell

Group Manager Integrated Catchment

Management

|

|

Attachment/s

There are no

attachments for this report.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL

COUNCIL

Wednesday 15 April 2020

Subject: Select Committee Report

on the Resource Management Amendment Bill

Reason for Report

1. This item is to provide Council with an update on the Select

Committee Report to the Resource Management Amendment Bill.

Executive Summary

2. The Environment Select Committee released their report on the

Resource Management Amendment Bill on 30 March 2020.

3. The report recommends general adjustments to resource management and

a new freshwater planning process, and introduces the inclusion of climate

change considerations in Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) decision making.

Background

4. The Resource Management Amendment Bill was introduced in September

2019 to:

4.1. reduce complexity in existing RMA processes, increase certainty for

participants, and restore previous opportunities for public participation

4.2. improve existing resource management processes and enforcement

provisions

4.3. improve freshwater management.

5. The Bill would make two notable changes to the existing resource

management system:

5.1. new enforcement powers would be given to the Environmental

Protection Authority

5.2. a new planning process for freshwater management would be

introduced.

6. Environment Select Committee have considered the Bill and released

their report on 30 March 2020. Their report provides commentary on

four key areas where they have recommended amendment to the Bill, these are:

6.1. improvements to general resource management processes

6.2. the Environmental Protection Authority’s new enforcement

powers

6.3. the new freshwater planning process and related changes

6.4. clarifying the relationship between the RMA and aspects of climate

change mitigation.

7. It should be noted that whilst staff have reviewed the Report they

have yet to review the tracked changes to the Resource Management Bill, or to

make any assessment or judgement as to the implications the proposed recommendations

will have for Regional Council functions.

Discussion

Improvements

to general resource management processes

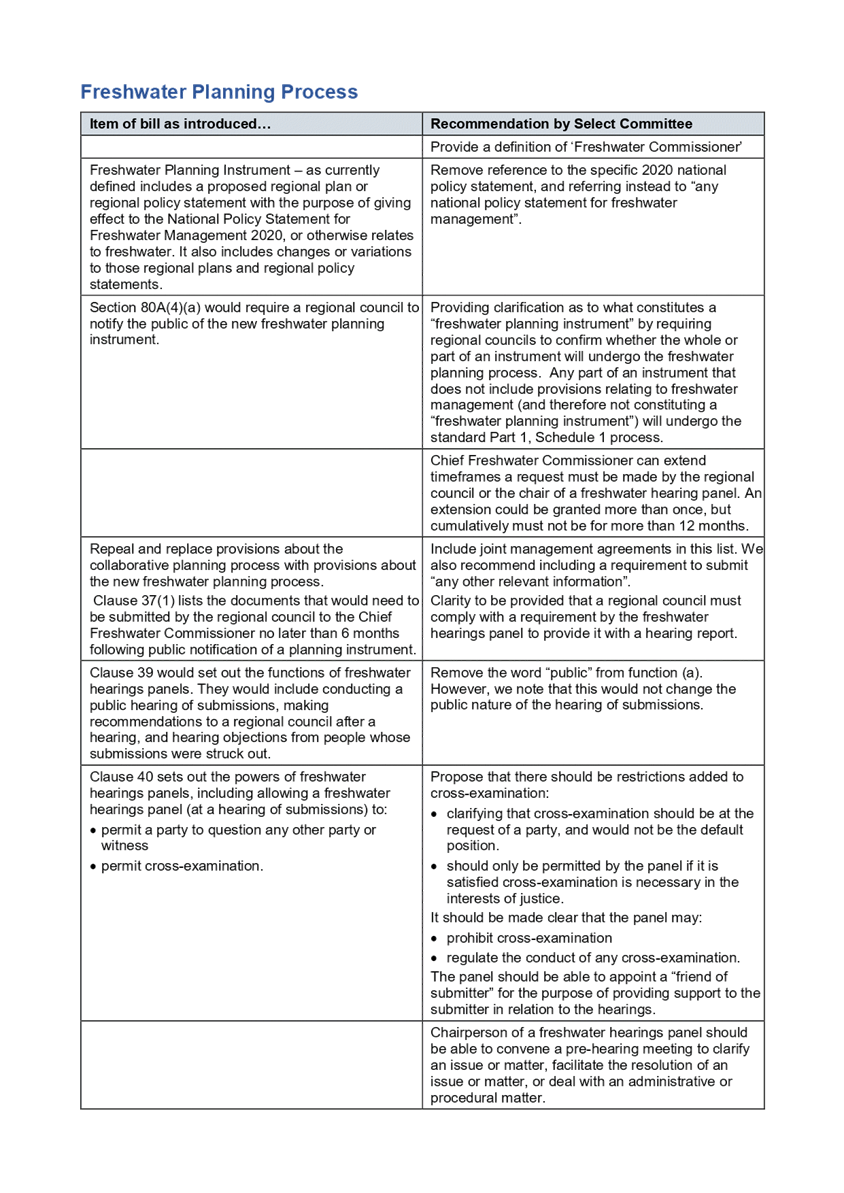

|

Item of bill as introduced…

|

Recommendation by Select Committee

|

|

…enables applicants to suspend the processing of non-notified

consent applications for up to 20 working days.

|

Delay new regime to allow councils time to update their processes and

procedures.

|

|

…allows councils to exclude such a time period from the

statutory time limit, in respect of unpaid fixed charges required when the

consent application is lodged or notified.

|

Delay commencement of these provisions by 3 months to give

Councils more time to update their processes and procedures.

|

|

…would give new powers to the EPA. They would enable the EPA to

initiate its own RMA investigations, to assist councils with their RMA

investigations, and to intervene in RMA cases to become the lead agency of an

investigation and subsequent enforcement actions.

|

Clarification sought - if the EPA ceases an intervention, a local

authority may resume any enforcement action that the local authority had

commenced prior to the EPA’s intervention.

|

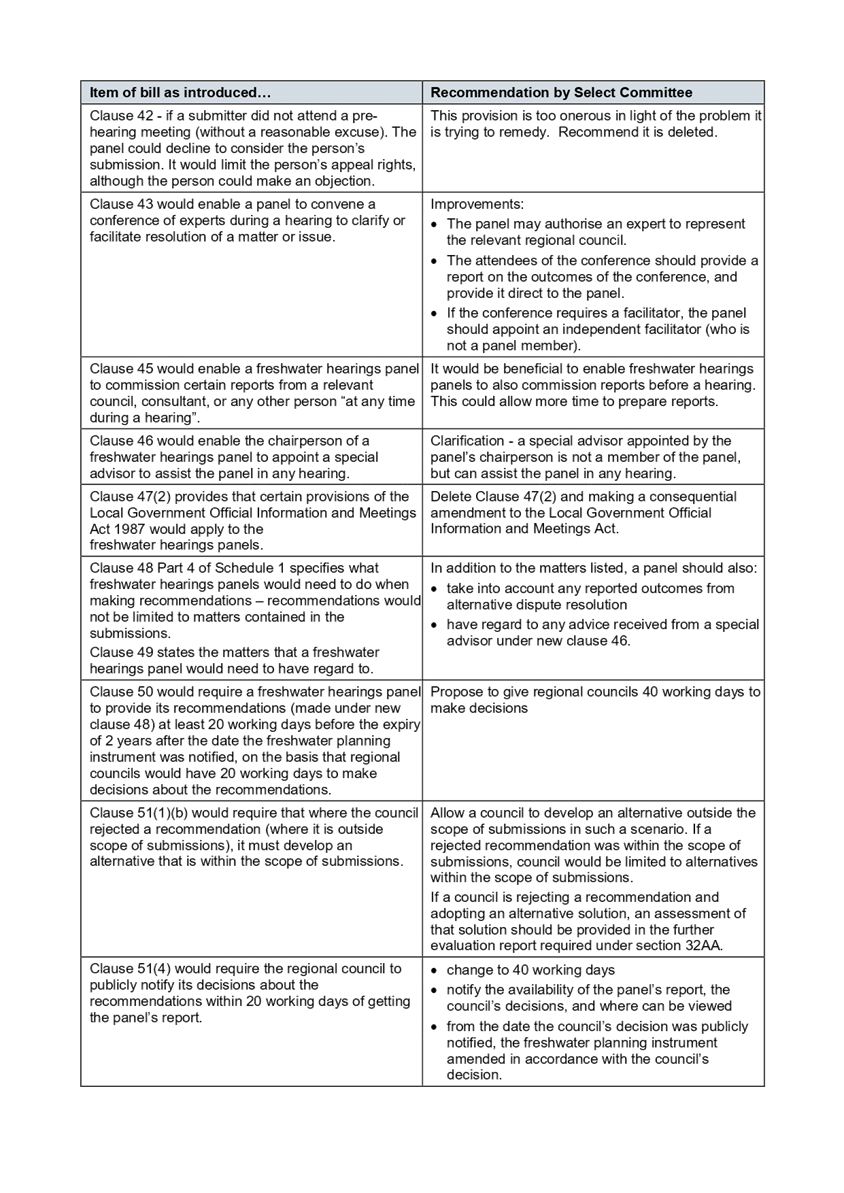

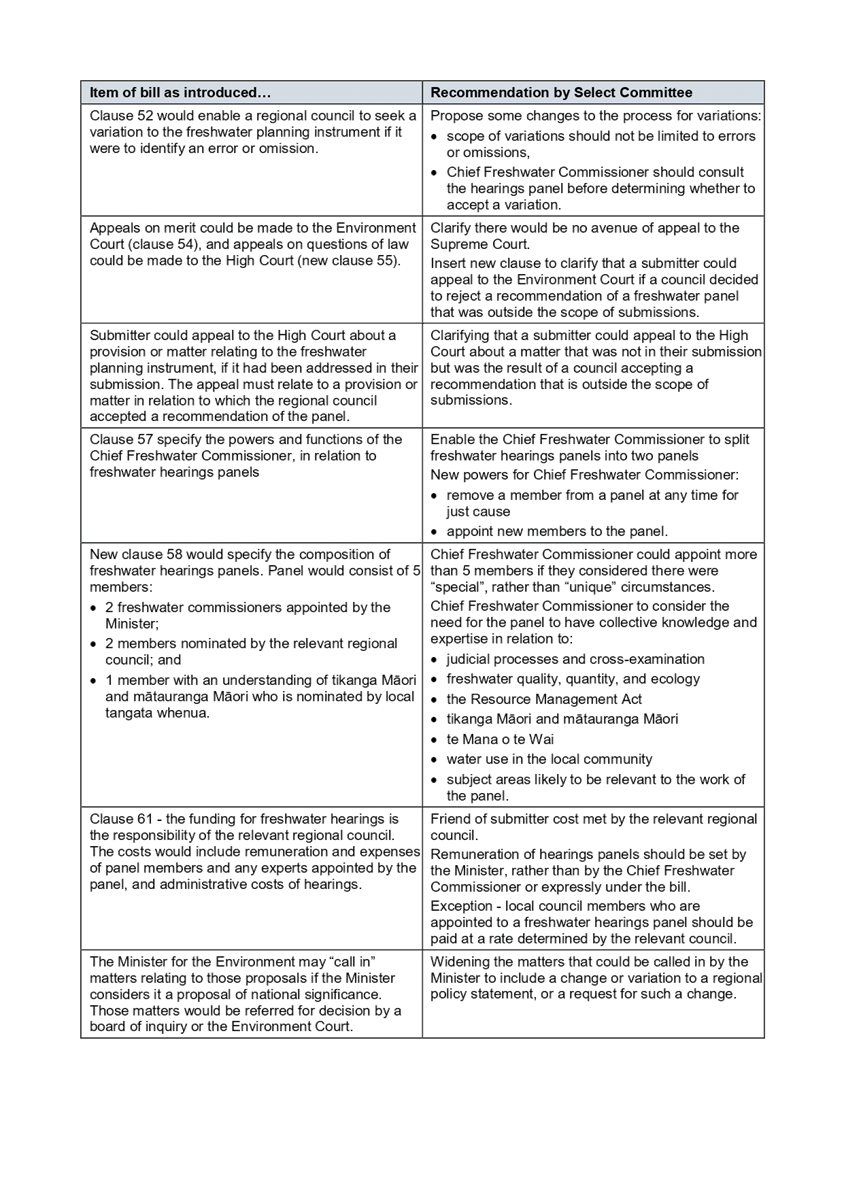

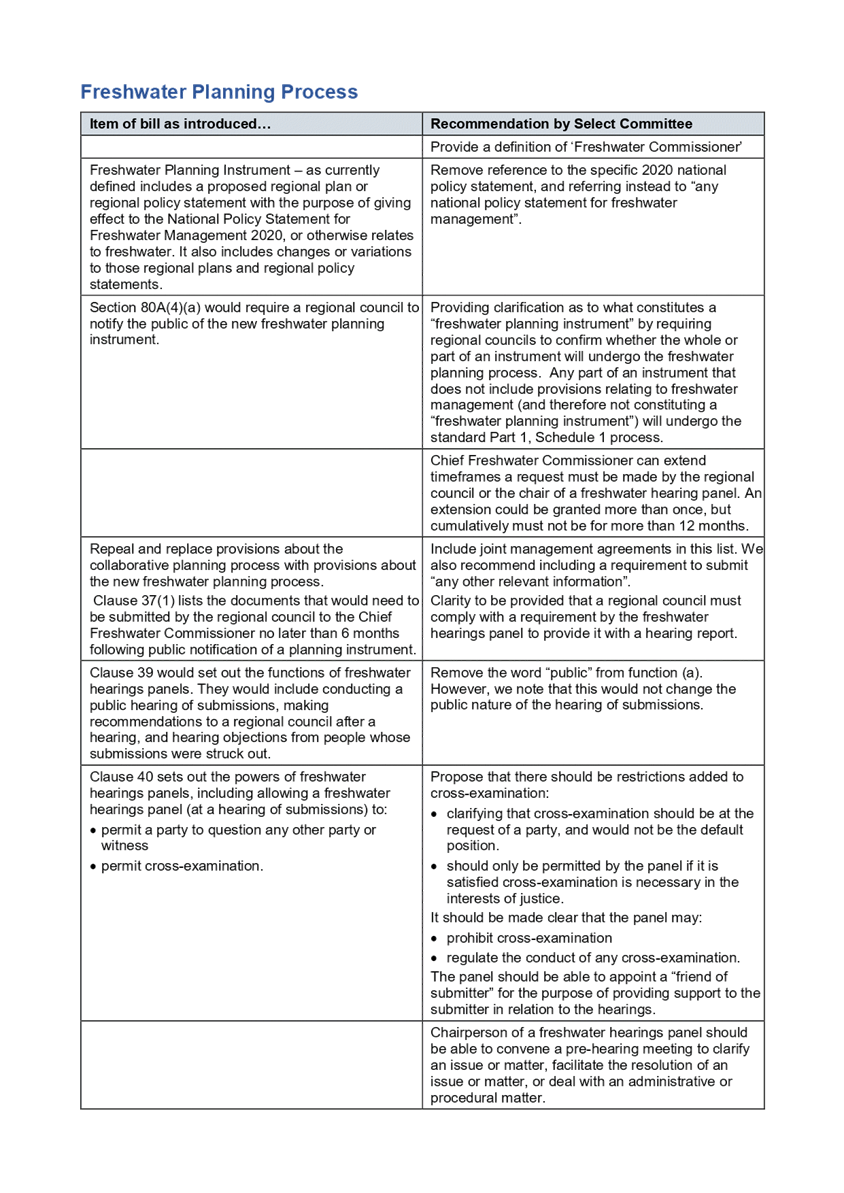

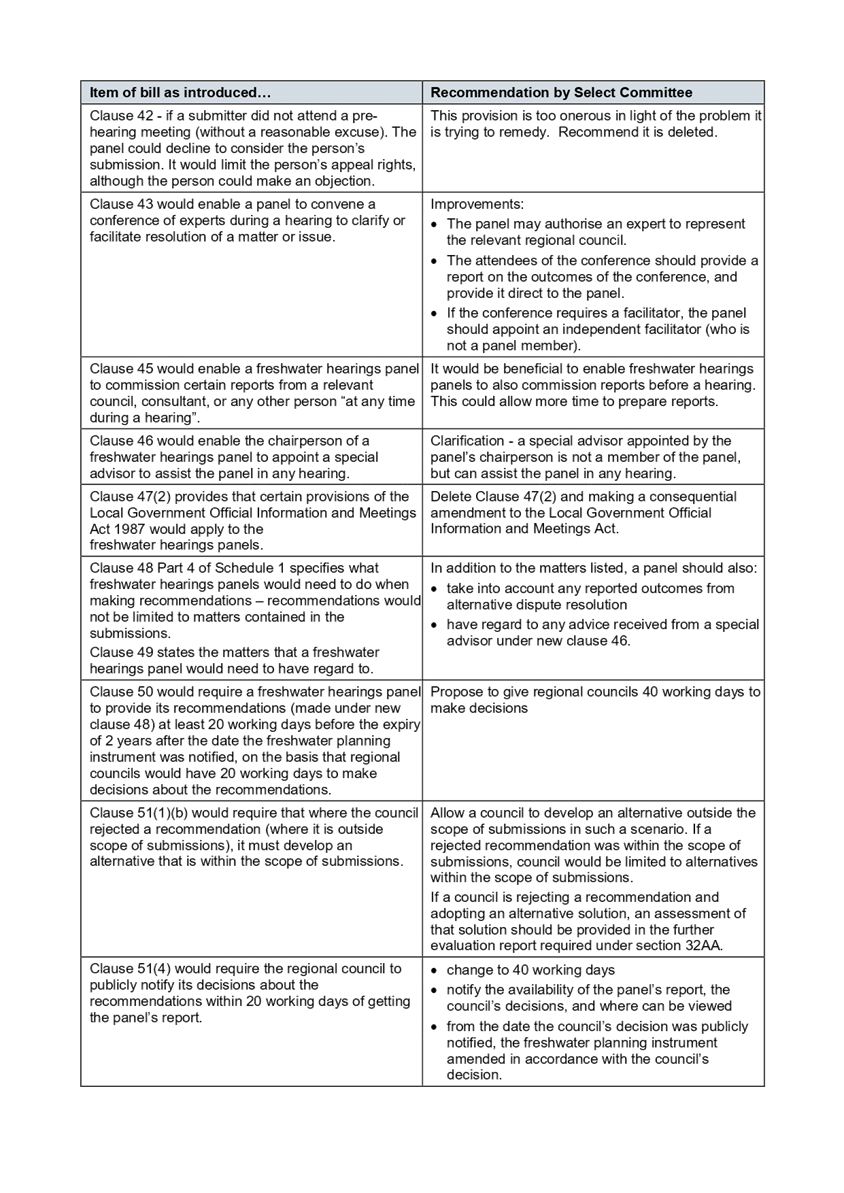

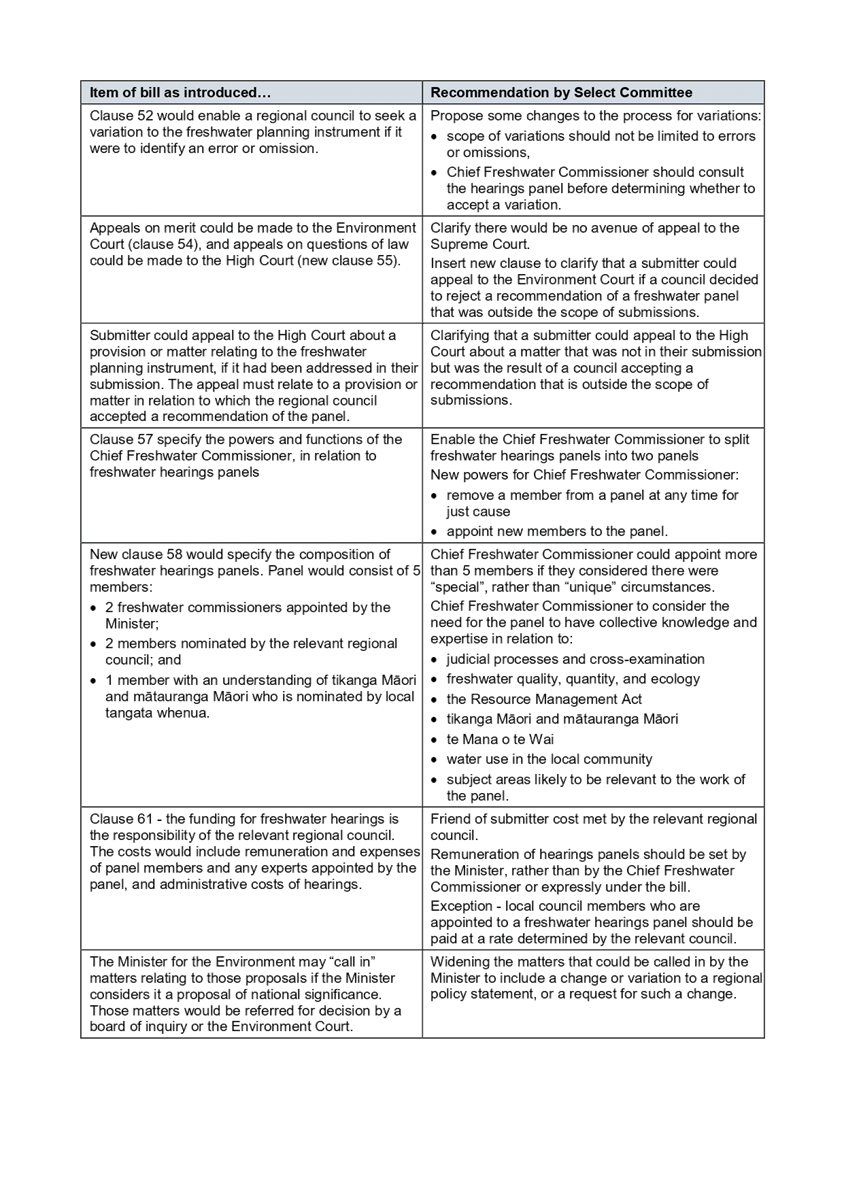

Freshwater Planning Process

8. Regional councils will be required to follow the new freshwater

planning process for proposed regional policy statements and regional plans

(including changes to them) that contain provisions that give effect to the

National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management.

9. Brookfields (Lawyers) have provided a useful summary of the Select

Committee’s key recommendations (much of which is replicated below)

concerning the new freshwater planning process. Staff have collated a more

detailed table summarising the recommendations in attachment 1.

9.1. Providing clarification as to what constitutes a “freshwater

planning instrument” by requiring regional councils to confirm whether

the whole or part of an instrument will undergo the freshwater planning

process. Any part of an instrument that does not include

provisions relating to freshwater management (and therefore not constituting a

“freshwater planning instrument”) will undergo the standard Part 1,

Schedule 1 process (clause 13 of the Bill)

9.2. Widening the matters that could be “called in” by the

Minister to include a change or variation to a regional policy statement, or a

request for such a change (clauses 28A to 28K of the Bill) (currently matters

include resource consent applications, notices of requirement, and council and

private plan changes)

9.3. Providing a power for the Chief Freshwater Commissioner to extend

various timeframes and providing 40 days (rather than 20) for regional councils

to make decisions on panel recommendations (new clauses 46A and 50 added to

Schedule 1 by clause 72 of the Bill)

9.4. Adding restrictions to cross-examination including that it should be

at the request of a party, and not the default position, and should only occur

if the panel is satisfied that cross-examination is necessary in the interests

of justice. It is also recommended that the panel may appoint a

“friend of submitter” for any submitter (new clauses 46 and 47

added to Schedule 1 by clause 72 of the Bill)

9.5. Allowing councils in making their decisions to develop alternatives

outside the scope of submissions and clarifying corresponding appeal

rights. In that regard it is noted that, if the rejected

recommendation from the panel were within the scope of submissions, the

council’s decision would also be limited to the scope of submissions (new

clauses 51, 54 and 55 added to Schedule 1 by clause 72 of the Bill)

9.6. Changes to the process for variations, including in particular that

variations not be limited to errors or omissions (new clause 52 added to

Schedule 1 by clause 72 of the Bill)

9.7. Adding matters to be taken into account by the Chief Freshwater

Commissioner in appointing panels, such as knowledge and expertise in relation

to judicial and RMA processes and tikanga Māori and amending matters in

relation to costs and panel remuneration (new clauses 58, 59, 61 and 63 added

to Schedule 1 by clause 72 of the Bill).

10. The

report notes that section 360(1)(hn) RMA allows regulations to restrict stock

from water bodies including prescribing fencing requirements or riparian

planting. It recommends that section 360(1)(hn) be extended to allow

regulations to exclude stock from the margins of water bodies, estuaries, and

coastal lakes and lagoons (clause 70).

The RMA - Relationship with Climate

Change Mitigation

11. The

recommendations introducing climate change considerations are:

11.1. Removing

the current statutory barriers to consideration of climate change in RMA

decision-making and adding “emissions reductions plans” and

“national adaptation plans” to the list of matters that local

authorities must have regard to when making and amending regional policy

statements, regional plans, and district plans. This would be

effective from 31 December 2021 to allow for those plans to be developed under

the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 processes (clauses

12C to 12G, 25A and 25B of the Bill).

11.2. This

transitional phase would not apply to Boards of Inquiry or the Environment

Court where matters are “called in” so that these bodies may take

global environmental impacts (including climate change mitigation) into

account from the date of the Bill’s commencement. The report

explains that this is to help ensure that large-scale projects that may have

high emissions are not brought forward to take advantage of the delayed

commencement of provisions concerning the “emissions reductions

plans” and “national adaptation plans”.

12. The

Select Committees report acknowledges that it will be vital to have direction

at a national level about how local government should make decisions about

climate change mitigation under the RMA. Otherwise, there could be risks of

inconsistencies, overlap of regulations between councils and emissions pricing,

and litigation.

Next

Steps

13. The Bill

will enter its second reading. At this stage, members of Parliament debate the

select committee report and vote on the Bill. If the vote fails, the Bill goes

no further. If the vote passes, the Bill will be considered by the Committee of

the Whole House, be read (and voted on) a third time and, if successful again,

the Bill will be signed by the Governor-General and become an Act.

14. No dates

for these further steps have been set, and staff will provide updates as and

when appropriate.

Decision Making

Process

15. Staff have assessed the

requirements of the Local Government Act 2002 in relation to this item and have

concluded that, as this report is for information only, the decision making

provisions do not apply.

|

Recommendation

That Hawke’s Bay Regional Council

receives and notes the “Select Committee Report on the Resource

Management Amendment Bill” staff report.

|

Authored by: Approved

by:

|

Ellen

Robotham

Policy Planner

|

Ceri Edmonds

Manager

Policy and Planning

|

Attachment/s

|

⇩1

|

Freshwater

Planning Process

|

|

|

|

Freshwater

Planning Process

|

Attachment 1

|