Meeting of the Hawke's Bay Regional Council Maori

Committee

Date: Tuesday 25 February 2014

Time: 10.15 am

|

Venue:

|

Council Chamber

Hawke's Bay Regional Council

159 Dalton Street

NAPIER

|

Agenda

Item Subject Page

1. Welcome/Notices/Apologies

2. Conflict of Interest Declarations

3. Short Term Replacements

4. Confirmation of Minutes of the

Maori Committee held on 3 December 2013

5. Matters Arising from Minutes of the Maori Committee held

on 3 December 2013

6. Follow Ups from Previous Maori Committee Meetings

7. Call for any Minor Items Not on the Agenda

Decision Items

8. Submission to the Local Government Commission on the Draft

Proposal for HB Local Government Reorganisation

Information or Performance Monitoring

9. Update on Current Issues by the Interim Chief Executive

10. Greater Heretaunga Ahuriri Plan Change TANK Group Update

11. HB District Health Board "Healthy Homes"

presentation

12. The Establishment of Taiwhenua - verbal report by Dr Roger Maaka

13. Statutory Advocacy Update

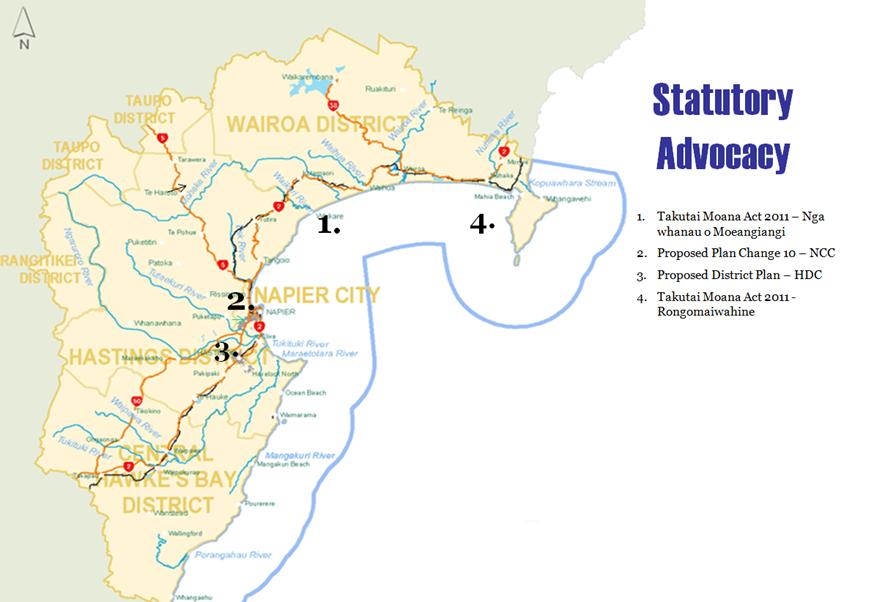

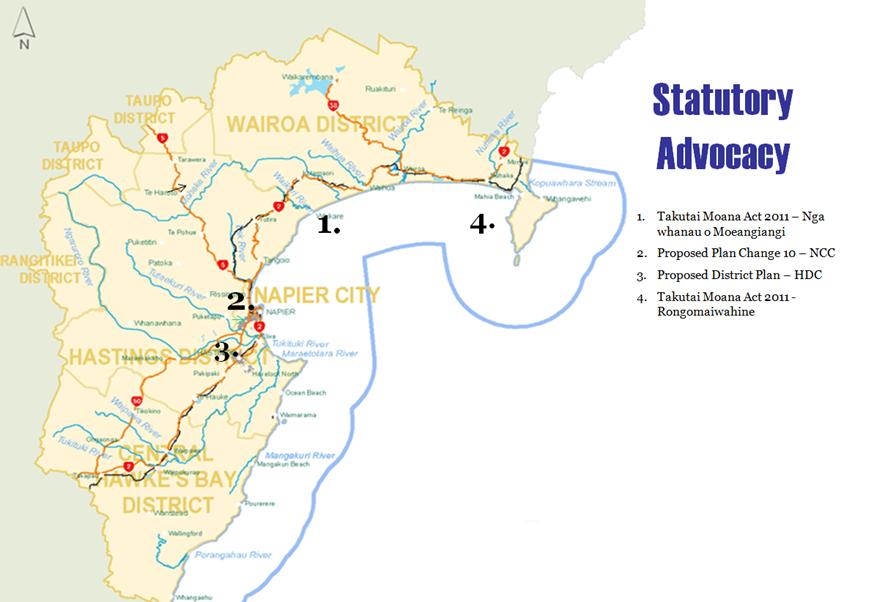

14. Minor Items Not on the Agenda

Please Note - Pre Meeting for Māori Members of

the Committee begins at 9 am

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Maori

Committee

Tuesday 25 February 2014

SUBJECT: Short Term Replacements

REASON FOR REPORT:

1. Council has made

allowance in the terms of reference of the Committee for short term

replacements to be appointed to the Committee where the usual member/s cannot

stand.

|

RECOMMENDATION:

That the

Maori Committee agree:

That ______________ be appointed as member/s

of the Maori Committee of the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council for the meeting of

Tuesday, 25 February 2014 as short term replacements(s) on the Committee for

________________

|

|

Viv Moule

Human

Resources Manager

|

Liz Lambert

Chief

Executive

|

Attachment/s

There are no

attachments for this report.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Maori

Committee

Tuesday 25 February 2014

SUBJECT: Follow Ups from Previous Maori

Committee Meetings

Introduction

1. Attachment

1 lists items raised at previous meetings that require actions or

follow-ups. All action items indicate who is responsible for each action, when

it is expected to be completed and a brief status comment. Once the items have

been completed and reported to Council they will be removed from the list.

Decision

Making Process

2. Council is required to make a decision in accordance with

Part 6 Sub-Part 1, of the Local Government Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have

assessed the requirements contained within this section of the Act in relation

to this item and have concluded that as this report is for information only and

no decision is required in terms of the Local Government Act’s provisions, the

decision making procedures set out in the Act do not apply.

|

Recommendation

1. That the Maori Committee receives the report “Follow

ups Items from Previous Maori Committee Meetings”.

|

|

Viv Moule

Human

Resources Manager

|

Liz Lambert

Chief

Executive

|

Attachment/s

|

Follow Up Items

|

Attachment 1

|

Follow Ups from Previous Maori Committee Meetings

3 December 2013 meeting

|

|

Agenda Item

|

Action

|

Person Responsible

|

Due Date

|

Status Comment

|

|

1.

|

Ngati Kahungunu Iwi

Incorporated Marine And Freshwater Fisheries Strategic Plan

|

Strategic Plan to be referred back

to Ngati Kahungunu for further consultation

|

MM/VM

|

Ongoing

|

Verbal update at 25 February Committee

meeting

|

|

2.

|

Update on Current Issues

|

Copy of Amalgamation

report to be circulated to Committee members

Copy of list of members

on TANK Stakeholder Group

|

MD

|

Following meeting

|

Completed and sent out with unconfirmed

mins

|

|

3.

|

Air Quality Monitoring Report

|

Heatsmart Update on DHB

findings

|

Vm/MH

|

23 February

|

Verbal report to be presented to 25

February meeting

|

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Maori

Committee

Tuesday 25 February 2014

SUBJECT: Call for any Minor Items Not on the Agenda

Reason for Report

1. Under standing orders,

SO 3.7.6:

“Where an item is not on the agenda for a

meeting,

(a) That item may be discussed at

that meeting if:

(i) that

item is a minor matter relating to the general business of the local authority;

and

(ii) the

presiding member explains at the beginning of the meeting, at a time when it is

open to the public, that the item will be discussed at the meeting; but

(b) No

resolution, decision, or recommendation may be made in respect of that item

except to refer that item to a subsequent meeting of the local authority for

further discussion.”

2. The Chairman will

request any items councillors wish to be added for discussion at today’s

meeting and these will be duly noted, if accepted by the Chairman, for

discussion as Agenda Item 16

|

Recommendations

That Maori

Committee accepts the following minor items not on the agenda, for discussion

as item 16.

1.

|

|

Leeanne Hooper

Governance

& Corporate Administration Manager

|

Liz Lambert

Chief

Executive

|

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Maori

Committee

Tuesday 25 February 2014

SUBJECT: Submission to the Local Government Commission on the Draft

Proposal for HB Local Government Reorganisation

Reason for Report

1. At its meeting on 18

December 2013 Council resolved to lodge a submission to the Local Government Commission

on its Draft Proposal for the reorganisation of local government in Hawke’s

Bay, based upon reinforcing the need for any local government structure within

Hawke’s Bay to have a specific focus on the management of natural resources in

recognition of the region’s strong linkages to its primary production sector.

2. A draft submission has

been considered by the Environment and Services Committee and changes suggested

at that meeting have been incorporated into the attached submission. The draft

submission has also been considered by the Regional Planning Committee and

their feedback will be provided verbal at the meeting. (Attachment 1) The

submission is being presented to Council on 26 February for final sign-off.

Feedback is sought from the Committee to ensure that any relevant points the

Committee wishes the Local Government Commission to address in its final

proposal are included in the submission.

3. Submissions close on 7

March 2014.

Decision Making

Process

4. Council is required to

make a decision in accordance with the requirements of the Local Government Act

2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed the requirements contained in Part 6 Sub

Part 1 of the Act in relation to this item and have concluded the following:

4.1. The decision does not

significantly alter the service provision or affect a strategic asset.

4.2. The use of the special

consultative procedure is not prescribed by legislation.

4.3. The decision does not

fall within the definition of Council’s policy on significance.

4.4. The persons affected by

this decision are all those persons with an interest in the delivery of local

government functions in Hawke’s Bay.

4.5. Options previously

considered by Council at its Corporate and Strategic Committee meeting 11

December 2013, and resolved at the Regional Council meeting 18 December

2013 included not lodging a submission.

4.6. The decision is not

inconsistent with an existing policy or plan.

4.7. Given the nature and

significance of the issue to be considered and decided, and also the persons

likely to be affected by, or have an interest in the decisions made, Council

can exercise its discretion and make a decision without consulting directly

with the community or others having an interest in the decision.

Notwithstanding this, any person may make a submission on the Local Government

Commission’s draft reorganisation proposal.

|

Recommendations

That the

Maori Committee:

1. Considers

the key points to be presented in the submission to the Local Government

Commission and provides feedback to assist in the

finalising of the submission.

The Maori

Committee recommends Council:

2. Agrees

that the decisions to be made are not significant under the criteria

contained in Council’s adopted policy on significance and that Council can

exercise its discretion under Sections 79(1)(a) and 82(3) of the Local

Government Act 2002 and make decisions on this issue without conferring

directly with the community and persons likely to be affected by or to have

an interest in the decision due to the nature and

significance of the issue to be considered and decided.

3. Approves

the submission, including any amendments agreed at the Maori Committee

meeting, for lodging with the Local Government Commission.

|

|

Liz Lambert

Chief

Executive

|

|

Attachment/s

|

1View

|

Updated Draft

Submission

|

|

|

|

Updated Draft Submission

|

Attachment 1

|

Draft

Submission

To: Local

Government Commission

Subject: Draft

Proposal for Local Government Reorganisation in Hawke’s Bay

Overview

The Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council (HBRC) welcomes the opportunity to submit on the Local Government

Commission’s draft proposal for local government reorganisation in Hawke’s Bay.

HBRC requests the

opportunity to be heard in support of its submission by the Commission.

HBRC seeks to

assist the Local Government Commission through its submission by noting a

number of matters which we consider should be given greater consideration by

the Commission in its decision making on whether or not to proceed to a final

proposal and, if so, what that final proposal should look like.

The Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council is the only local authority within the area affected by the

draft proposal that represents all the communities within that area. In our

view this allows the regional council to provide a greater level of

independence in respect of the communities of interest.

HBRC submitted an

Alternative Proposal for local government reorganisation when this was called

for by the Local Government Commission in March 2013. While the structure in

our alternative proposal by HBRC has not been accepted as a reasonably practicable

option our submission expresses concern that the principles outlined in that

alternative proposal, which are a fundamental of good local governance, have

not been addressed in any sense in the draft proposal.

The basic

contention of this submission is to provide solutions for the Commission to

consider in addressing these fundamentals of good local governance.

Rationale

The underlying

premise of HBRC’s submission is that form should follow function when it comes

to determining local government structure. In HBRC’s view the draft proposal

has not given adequate consideration of existing local government functions but

rather focuses on what local government might potentially do in a unitary

authority (noting that this is set out in the draft proposal without supporting

evidence).

A provincial

unitary council on the scale of Hawke’s Bay has not been contemplated before.

The current proposals for Northland are also of a smaller scale. Two thirds of

the new unitary Council’s population would be based in Napier and Hastings. Six

of the nine elected councillors will represent the Hastings and Napier wards.

Their interests and political mandates are likely to be influenced more by

urban than rural concerns, and more by matters of a territorial authority nature

than those of a regional council. With only ten politicians governing the

Hawke’s Bay Council, the distance between them and the community, particularly

in the rural area will increase. The specialist political representation and

knowledge of rural and natural resources is likely to be lost to a significant

degree.

Natural resource

knowledge and management, providing an integrated approach and specialist

expertise to natural resource management is a core function regional councils.

This is particularly essential to Hawke’s Bay given the region’s significant

natural resource base including large areas of land suitable for intensive

agriculture or horticulture and given that the region’s economy is driven by

primary production.

The

region needs to retain a core focus on ensuring the investment funds deliver

intergenerational work in the complex natural resource areas and the investment

capital is used for critical regional scale infrastructure which unlocks

sustainable economic opportunities. A dedicated focus on assisting the primary

sector to build resilience, and if possible to expand, also needs to be

retained in any future structure.

While it

is accepted that any regional council regulatory functions would need to

continue irrespective of structure the arguably more important contribution of

the regional council is in undertaking scientific investigations of natural

resources, particularly freshwater, and in adding value through the use of

investment capital for critical regional scale infrastructure which unlocks

sustainable economic opportunities.

Draft

Proposal

Key elements of the

draft proposal are:

· Amalgamation of current councils into

one unitary authority.

· Inclusion of small area of Rangitikei

district currently within Hawke’s Bay Regional Council into new council

· Exclusion of two areas of Taupo

district currently within Hawke’s Bay Regional Council from new council HOWEVER

the new Hawke’s Bay council would be responsible for regional council functions

in these areas (transferred from Bay of Plenty Regional Council)

· Nine councillors would be elected from

five wards. The Mayor would be elected at large

· The council would have five community

boards with 37 elected members.

· A standing council committee

comprising representatives of local iwi and elected members of council would

hear the views of Māori

· Existing council debt and financial

arrangements would be ring-fenced for at least six years to the communities

which incurred them or benefit from them. Current regional assets would be transferred

to Hawke’s Bay Council.

Commentary

Regional Council functions

The

regional council is particularly focussed on the issues of environmental

management, rural land use and primary production, and how this is linked to

the performance of the regional economy. This is built upon a focus on

freshwater management and soil/land management. The 2011 National Policy

Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS) means that regional councils are and

will be busy with a number of significant issues in its implementation,

including:

· Reviewing key planning documents in order to "give

effect to" the NPS

· Developing freshwater objectives and quality and

quantity limits

· Grappling with issues of "efficient

allocation", "efficient use" and water permit transfer criteria

· Reviewing discharge permit consent conditions

· Increasing the involvement of iwi and hapū and

improving the integrated management of fresh water.

This is leading to

considerable policy and plan development by regional councils over the next few

years on what are very contentious issues. The work required to underpin

the setting of limits is complex, quite sophisticated and is going to take the

best part of a decade to work through.

Of concern to HBRC

in the establishment of a unitary authority is the focus on territorial

authority activities. While this is understandable, and is not a criticism, it

does lead to questions around the ongoing financial sustainability of the

programmes required to be undertaken over long term periods to validate the

policies required to be developed, not just in the area of freshwater

management but in the management of other public resources such as air, land

and the coast.

In recognition of

the responsibilities placed on regional councils to manage the “commons” without

the ability to recover costs directly, regional councils were transferred

ownership of port companies in the 1989 New Zealand-wide local government

reorganisation. The Hawke’s Bay Regional Council relies on the dividend paid to

it annually by the Port of Napier Ltd to allow it to undertake scientific

investigations, environmental monitoring and land management activities that

would otherwise have to be funded directly by the ratepayer. HBRC’s concern is

that the funding of such activities is vulnerable to the more immediate needs

often associated with urban based council activities.

The tone of

regional council decisions is different to that of territorial authorities. Of

necessity regional councils generally takes a long-term strategic look at its decisions

as these involve long-term outcomes and significant, ongoing financial

resourcing. In that regard HBRC believes that the formation of an elected rural

and natural resources special purpose board with advisory and/or decision

making functions should also be completed by the Commission, so that specialist

governance input for regional council functions will be adequately provided to

a future Hawke’s Bay Council.

We request that the

dividend paid by the Port of Napier Ltd be “ring-fenced” for regional council

environmental management functions in the final proposal. It is the Regional

Council’s understanding that such “ring-fencing” can be undertaken in

perpetuity and is not limited by a six-year maximum term.

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for local government

re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay that excludes the retention of a stand-alone

regional council includes provision for the ring-fencing of the dividend paid

to the local authority by the Port of Napier Ltd for expenditure on the

following functions:

· Environmental air

quality control

· Natural resource

environmental monitoring

· Biosecurity

· Harbourmaster

functions/navigation and safety

· Land management

· Regional resource

management planning

· Coastal planning

and management

· Freshwater science

investigations, including water allocation and water quality monitoring

· Stormwater and

wastewater regulations

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for local government

re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay that excludes the retention of a stand-alone

regional council includes provision for the establishment of an elected Natural

Resources Board to provide specialist governance input for the regional council

functions of the Hawke’s Bay Council.

A stand-alone regional

council

The Draft Proposal

rejects the concept of one Hawke’s Bay District Council and one Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council on the basis that it would be seen as creating confusion in

the public mind as to who had political mandate to speak for Hawke’s Bay. No

other considerations that are required to be assessed by the Local Government

Commission are presented in the draft proposal in relation to this option e.g.

whether or not this option facilitates efficiencies and cost savings;

productivity improvements and simplified planning processes.

Amendments

to the Local Government Act in December 2012 mandate that any proposed

reorganisation must ‘promote good local government’ by facilitating:

· Efficiencies and cost savings;

· Productivity improvements, both within

the affected local authorities and for the businesses and households that

interact with those local authorities; and

· Simplified planning processes within

and across the district or region through, for example, the integration of

statutory plans or a reduction in the number of plans to be prepared or

approved by the local authority.

In addition any

proposed authority must –

· Have the resources necessary to enable

it to carry out effectively its responsibilities, duties and powers;

· Contain within its district or region

1 or more communities of interest, but only if they are distinct communities of

interest;

· Enable catchment-based flooding and

water management issues to be dealt with effectively by the unitary authority.

The legislation

does not specify that the issue of political mandate to speak for an area is a

criterion for the promotion of good local government. The draft proposal fails

to address the matters that the Local Government Act 2002 specifies must be

facilitated by any proposed reorganisation and therefore fails to give the

submitting public of Hawke’s Bay an opportunity to explore the rationale for

the rejection of a stand alone regional council.

Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council seeks that any final proposal for local government re-organisation in

Hawke’s Bay that excludes the retention of a stand-alone regional council

includes a detailed analysis of the rationale for the Local Government

Commission rejecting a stand- alone council in accordance with all the required

provisions of the Local Government Act 2002.

Community Boards

The effectiveness

of the “local voice” in the draft proposal relies to a large extent on the

existence of the community boards. The draft proposal notes that it may be

possible that the passing of local government legislation amendments will allow

for the provision of local boards in Hawke’s Bay.

A unitary authority

with community boards does not guarantee the effective representation of Hawke’s

Bay’s communities or the delivery of local services based on communities’

needs. The existence of community boards is subject to a six-yearly

representation review at which point the Hawke’s Bay Council could form a view

to abolish or reconstitute them. In addition the powers and duties of a

community board are largely determined by the governing body (the Hawke’s Bay

Council). Such a hierarchical model does not guarantee the sustained, strong,

localised governance needed in an area like Hawke’s Bay, nor does it enhance

the relationship of the ratepayer to the authority that sets its rates.

Should the required

legislation be passed to allow for local boards the Hawke’s Bay Regional

Council requests that the Local Government Commission, as provided for in

Clause 21 (1) C) of Schedule 3 of the Local Government Act 2002, identify

another preferred option as the basis of a new draft proposal. We do not

consider that the issuing of a modified draft proposal would be satisfactorily

transparent. The public of Hawke’s Bay need to be able to know what a local

board is and what it can do on their behalf, how it and its activities are

funded, and the extend of its decision making powers.

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council seeks that a revised draft proposal be issued to enable public

submissions to be lodged in the event that the Local Government Commission

determines that it wishes to see the establishment of local boards for Hawke’s

Bay, should the requisite legislation be passed.

Māori representation

Underpinning

the people, the economy and the environment is the development of an

appropriate co-governance model. A resilient and sustainable planning

framework is coming out of the co-governance Regional Planning Committee of the

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council, which maintains equal numbers of iwi (represented

by mandated Treaty settlement groups) and elected regional representatives at

the table, debating and making recommendations for future natural resource

management. Through reforms to the Resource Management Act the Government is

seeking to ensure that Māori

interests and values are considered earlier in resource management planning

processes with solutions developed up-front.

The draft proposal

provides for the establishment of a standing committee to hear the views of

Māori. The Hawke’s Bay Regional Planning Committee, comprising equal

representation of elected representatives and mandated treaty groups, will be

in place legislatively by the time the Local Government Commission issues its

final proposal. HBRC considers it essential that the final proposal, or a new

draft proposal, includes clarification of the relationship between the Regional

Planning Committee roles and responsibilities and that of the standing

committee.

The Regional Planning Committee model, being

based upon Treaty settlement groups, ensures that all appropriate iwi are

represented at the decision-making table through their mandate. It also meets

their needs as part of their cultural redress sought through Treaty claims on

the management of natural resources.

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for local government

re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay that excludes the retention of a stand-alone

regional council includes clarification around the roles and responsibilities

of the Māori Standing Committee and the legislated Regional Planning

Committee. This is important as while the Māori Standing Committee will

act in an advisory role only the Regional Planning Committee has a

co-governance role. The expectations arising these two separate arrangements

need to be made clearer to the public.

Taupo

The draft proposal

creates an unacceptable level of uncertainty around the exclusion of two areas

of Taupo district currently within the Hawke’s Bay Regional council area from

the new unitary authority. These two areas are in the headwaters of the Mohaka

River, Hawke’s Bay’s longest river. There is a small usually resident

population within these two areas (2011 est: 90) and the land is predominantly

high country indigenous bush and scrub, with the balance in forestry and

farming. The total area is around 78,500 ha.

It is clear that in

the draft proposal the Commission considers that community of interest has

primacy over catchment. It proposes that these areas remain with Taupo

district, and be included in the Bay of Plenty Regional Council area, but that

the regional council responsibilities in those two areas then be transferred to

the Hawke’s Bay Council under the final reorganisation scheme. No direction is

given in the draft proposal about how such activities would be funded and by

whom, whose resource management act provisions would apply and how any

differences could be resolved.

We note that:

· The LGC

noted that for the purposes of effective catchment management, two small areas

of Taupō district and one small area of Rangitikei district are presently

included in Hawke’s Bay region. Following discussion with Hawkes Bay Regional

Council (HBRC) officers, the LGC concluded that it would be important for these

areas to remain under the authority of any new Hawke’s Bay unitary authority,

at least for catchment and related purposes (Clause 175).

· The LGC

noted that the two small areas of Taupō district were in Hawke’s Bay

region, in order that the Mohaka River catchments were contained within the

boundaries of one regional council, i.e. HBRC. The LGC considered that it was

important that these catchments were not divided, given the national

significance of the river which has a conservation order on it, and which has

been the subject of a Waitangi Tribunal recommendation relating to interests of

Ngāti Pahauwera (Clause 177).

· On the

other hand, the LGC received correspondence from Taupō District Council

opposing the separation of these two areas from Taupō district, on

community of interest grounds (Clause 178). The LGC agreed there were strong

community of interest arguments for these areas to be kept within the

boundaries of Taupō district and also that this was likely to be supported

by Ngāti Tūwharetoa (Clause 179).

· In order to meet the conflicting

arguments, the LGC concluded that if one unitary authority were to be

established for Hawke’s Bay, the two areas of Taupō district should be

excluded from the new district but that responsibility for the regional council

functions presently being undertaken by HBRC, should continue to be the

responsibility of the new Hawke’s Bay unitary authority. This would involve

including these areas in the Bay of Plenty region and transferring the regional

council statutory obligations for these areas to the new Council under Section

24(1)(e) of the LGA (Clause 180).

Specifically, we are unclear how the transfer of statutory

obligations from BOPRC to the Hawke’s Bay Council would work in practice and

seek clarification on this matter, including but not limited to:

· Funding

- how the delivery of functions and services would be funded, including how

rating would work practically. Our understanding is that rating functions

cannot be transferred to another authority, so BOPRC would of necessity be the

rating authority for these areas.

· Governance

arrangements – how representation of residents and ratepayers for regional

council functions would operate, i.e. which Council(s) residents would vote

for, in terms of regional council functions, and whether this would be the same

Council that is delivering regional council functions and services in their

area.

· Resource

Management Act – how roles and responsibilities under this Act would operate

without creating inconsistencies and uncertainty. For example, if the two areas

in question were to be covered by the Bay of Plenty Regional Policy Statement

(which is currently based on entire catchments) and Bay of Plenty regional

plans, while resource consenting and regulatory roles were transferred to the

Hawke’s Bay Council.

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for

local government re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay clarifies the transfer of

statutory obligations from the Bay of Plenty Regional Council to the Hawke’s

Bay Council. It is extremely difficult for HBRC to determine a position of

support for this aspect of the proposal until these points of clarification

have been provided.

Further analysis

In our view the

draft proposal issued by the Local Government Commission in November 2013 is

inadequate in terms of detail. Before the Local Government Commission issues a

final proposal, or a new draft proposal, it must do much more analysis of the

current functions and responsibilities of the councils, the number of FTEs

associated with performing those functions and the costs of transition and

integration.

Robust data and

evidence must be provided in support of the preferred option so that the public

can understand what the true costs and benefits of the options are.

Much has been made

of the costs and benefits of the creation of the Auckland super-city, with

almost as many different accounts put forward as there are commentators. It

would be of huge assistance to the people of Hawke’s Bay to have an assessment

of the costs and benefits of the preferred option provided by the Commission to

assist them make up their minds.

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council requests that if the Commission determines that local boards

are to be included in the local government structure in Hawke’s Bay, and

include these in a re-issued draft proposal, it is critical that the cost and

resources associated with local board plans and agreements and the

administration and support services associated with them are quantified.

Transition arrangements

There is very

little detail about the transition phase in the draft proposal and particularly

about the resourcing requirements that may be required from councils. Given

that HBRC operates in as lean and efficient way as possible this is a potential

concern impacting on council functions during transition and the maintenance of

current levels of service to Hawke’s Bay.

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for local government

re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay that excludes the retention of a stand-alone

regional council includes detail on the transition phase in order to understand

what impacts this phase might have.

The draft proposal proposes that the Hawke’s Bay Council’s

administrative headquarters would initially be located in Napier City. However

if the transition board decides there is a more appropriate location it would

make a recommendation to the new council on the future location of the

headquarters. In our view the transition board should not be concerning itself

with a recommendation to the new council on the future location of the

headquarters. The transition period is brief enough as it is and it seems

inefficient and not cost effective to establish the body in one location and

potentially move it quickly to another. The new Council should have a period of

bedding in and aligning a range of existing organisations into one body before

considering the location of its headquarters.

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council seeks that any final proposal for

local government re-organisation in Hawke’s Bay specifies the location of the

council headquarters and service centres for a period of five years and removes

responsibility for making a recommendation on this from the Transition Board.

This time period is in line with the Commission’s proposal that Council

services would continue to be provided for at least five years at service

centres in existing council locations in Wairoa, Napier, Hastings, Waipawa and

Waipukurau. This would allow for a comprehensive review of all physical

locations of Council services at that time.

Conclusion

Hawke’s Bay

Regional Council is of the view that the draft proposal for local government

reorganisation in Hawke’s Bay does not provide sufficient certainty for the

ongoing resourcing and prioritisation of natural resource management functions in

Hawke’s Bay. This is critical for the ongoing economic development prospects of

the region. It would be helpful for the Local Government Commission to give

further consideration to a number of matters raised in our submission and we

are willing to provide assistance in this if asked.

Given the concerns

we have raised we are unable to support the draft proposal for Local Government

Reorganisation in Hawke’s Bay in its present form.

HAWKE’S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL

Maori

Committee

Tuesday 25 February 2014

SUBJECT: Greater Heretaunga Ahuriri Plan Change TANK Group Update

Reason for Report

1. This paper provides an update on the

TANK collaborative stakeholder group which is deliberating policies for the

Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri Plan Change. The TANK Group has published a

report summarising its work to date which is attached to this paper.

2. This update is similar

to a report presented to the Regional Planning Committee meeting on 19

February. Due to timing of that meeting and production deadlines for the Maori

Committee meeting agenda, timing did not allow this paper to record the

outcomes of the Regional Planning Committee’s discussion. At the Maori

Committee meeting, staff will present (any) recommendations made by the

Regional Planning Committee on this TANK project update.

Background

The TANK Group

3. The TANK Group was

convened in October 2012 to discuss land and water management options for the

Tutaekuri, Ahuriri, Ngaruroro and Karamu (TANK) catchments (surface and ground

water). Collectively this area is referred to as Greater Heretaunga and

Ahuriri.

4. The TANK Group is

comprised of 30 people from a range of backgrounds. The TANK Group’s brief is

to provide Council (via the Regional Planning Committee) consensus

recommendations regarding objectives, policies, limits and rules for a plan

change to the RRMP for the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri catchment area.

5. As well as making

recommendations on values and overall objectives, there are a number of key

regional planning provisions that the TANK Group is tasked with making

recommendations to Council on. These include:

5.1. flow regime, including low flow

restrictions on takes

5.2. water allocation (including for

municipal and domestic supply)

5.3. security of water supply for water

users

5.4. policies, rules on groundwater

/surface water connectivity

5.5. surface water and groundwater quality

limits

5.6. tangata whenua involvement in

freshwater decision making

5.7. use of Mātauranga Māori in

monitoring and reporting

5.8. wahi tapu register

5.9. policies, rules and incentives on:

5.9.1. riparian management and stock exclusion

5.9.2. water storage

5.9.3. water efficiency

5.9.4. water sharing/transfer

5.9.5. nutrient loss/allocation

5.9.6. good irrigation practices

5.9.7. stormwater management

5.9.8. other agricultural practices.

6. The Group was initially

scheduled to hold seven meetings through to July 2013 but due to the Plan

Change timeframe extension (adopted in the 2013/14 Annual Plan process), the

Group’s schedule was also extended. The Group has now held 11 meetings, the

most recent being on 10 December 2013. This makes parts of the Group’s existing

Terms of Reference obsolete meaning that this will be revised and updated.

The TANK Report

7. At the 10 December TANK

Group meeting, the Group approved its first report for public release. The TANK Interim Report summarises the TANK Group’s work

between October 2012 and December 2013 and provides a platform for the group to

proceed with future discussions. The Report was the result of extensive

discussion amongst the group over a series of meetings as well as

communications with the group’s networks over a three month period between

September and December 2013.

8. The

TANK Report is not a Council report; rather it is the TANK Group’s report

presented to Council and to be available to the wider public. It includes a set

of ‘Interim Agreements’ which are “supported in principle” by most (but not

all) parties on the Group, including the Regional Council (the Council being a

stakeholder).

9. The

TANK Report was intended to be publicly released in early January, however in

late December, Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated (NKII) expressed

that they had a number of significant concerns and would not be endorsing the

Report. Due to commitments associated with the Tukituki Board of Inquiry

hearing, NKII noted that they would not be able to outline their specific

concerns with the TANK Report until that hearing had concluded.

10. Given that the TANK Group had undertaken

significant effort over three months to get the Report to a form suitable for

public release, a short-term resolution to the matter was to add a ‘Report

Status’ section to record NKII’s concerns. Earlier concerns that had been

raised by Hastings District Council and Matahiwi Marae were relocated to this

new section from footnotes. As noted in

the Report, these concerns will be the subject of discussion when the TANK

Group reconvenes.

TANK Group and Ahuriri

11. At the Council meeting

on 28 November 2013, Council committed to engaging with Mana Ahuriri, the Crown

and other parties in the formation and function of the Ahuriri Estuary

Committee (AEC). An Agreement in Principle was signed that includes addressing

the needs of Mana Ahuriri to have a joint management regime for the Ahuriri

Estuary.

12. Also on 28 November, Tim

Sharp from Council’s Strategic Development Group, met Mana Ahuriri Iwi Inc

Board to discuss the TANK Group and TANK Report. It was noted that any outcomes

of the TANK process will need to be consistent with AEC. To achieve this most

effectively, it may be pertinent that a member of the AEC be nominated to the

TANK Group.

TANK Group next steps

13. The intention is for the Group to

continue to meet through to, and during, the drafting of the Plan Change. There

is still a lot of ground to cover before the Group will be in a position to

make well-informed decisions about the form and contents of the Plan Change.

There is a wide range of science, cultural and economic information necessary

to be provided to the TANK Group to assist their decisions. Much of this work

is still to be done.

14. In the immediate future, a number of

approaches are currently under consideration for the TANK Group to proceed

including:

14.1. exploring the TANK Report ‘matters of

concern’ which have been raised by some parties

14.2. reviewing and summarising

catchment-specific issues identified to date to hone in the areas the TANK

Group needs to focus on

14.3. reviewing the Tukituki Plan Change to

see which approaches and provisions may be transferable into Greater Heretaunga

and Ahuriri

14.4. applying the National Objectives

Framework (NOF) to waterways in the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri area to

determine whether preferred waterway ‘states’ (as described in the NOF) can be

agreed by TANK members. However, the NOF is only proposed at this stage and

hence it may be too early for the TANK Group to consider.

15. To progress the discussions efficiently,

it is intended that smaller groups will meet to discuss different topics (e.g.

catchment-specific matters which may not impact on the full Group). The full

Group is likely to meet every three months to review the findings of these

smaller groups.

16. It is recognised that the Tukituki BOI

process has required the significant commitment of resources from many parties,

many of whom are also involved with TANK (as well as other Council projects

including the Taharua/Mohaka Plan Change). To provide a bit of breathing space,

the TANK process has rescheduled its next meeting from early March to

mid-April. This timing means the next meeting will be held after the Tukituki

BOI draft decisions are made.

Tangata whenua

representation on the TANK Group

17. Some of the issues

arising through the BOI hearing on the Tukituki Catchment Plan Change 6

regarding tangata whenua consultation have highlighted the importance of

getting the tangata whenua representation on the TANK Group right.

18. In the formation of the

TANK Group, tangata whenua groups were invited to nominate a member to the TANK

Group to ensure a broad cross-section of interests from a range of hapu,

taiwhenua and iwi was represented. Tangata whenua members on the TANK Group are

currently: Terry Wilson (Mana Ahuriri Iwi Incorporated);

Ngaio Tiuka (Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated); Marei Apatu (Te

Taiwhenua ō Heretaunga); Morry Black (Matahiwi Marae); Peter Paku

(Ruahapia Marae); Jenny Mauger (Ngā Kaitiaki ō te Awa a Ngaruroro); Aki

Paipper (Ngāti Hori ki Kohupātiki); and Joella Brown (Te Roopu

Kaitiaki ō to Wai Māori).

Decision Making

Process

19. Council is required to

make a decision in accordance with Part 6 Sub-Part 1, of the Local Government

Act 2002 (the Act). Staff have assessed the requirements contained within this

section of the Act in relation to this item and have concluded that, as this

report is for information only and no decision is to be made, the decision

making provisions of the Local Government Act 2002 do not apply.

|

Recommendation

That the Māori

Committee receives the report titled ‘Greater Heretaunga Ahuriri Plan

Change TANK Group Update.’

|

|

Tim Sharp

Strategic

Policy Advisor

|

Gavin Ide

Manager,

Strategy and Policy

|

|

Helen Codlin

Group

Manager

Strategic

Development

|

|

Attachment/s

Collaborative decision making for

freshwater resources in the

Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri Region

TANK Group Report 1

Interim Agreements

|

|

|

|

Naku te rourou nau te rourou ka ora

ai te iwi

With

your basket and my basket the people will live

|

HBRC

Plan No.

Status

of this Report

This Interim Report summarises the TANK Collaborative Stakeholder

Group’s work between October 2012 and December 2013 and provides a platform for

the group to proceed with future discussions. It includes a set of ‘Interim

Agreements’ which are “supported in principle” by most parties but not all. It

is anticipated the areas of disagreement will be resolved as the TANK Group

continues its collaborative process in 2014. The following parties have

expressed their positions on this report:

· Due to the local

body election process, the Hastings District Council has expressed the need for

further time to consider this report and intends to provide feedback to the

TANK Group as soon as practicable in 2014. However, no obvious or significant

issues have been identified based on initial consideration.

· Matahiwi Marae has

raised a number of concerns with specific aspects of this report. These

specific concerns are noted in the report by way of footnote.

· Ngāti

Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated do not endorse this report as there are a number of

matters that they are not in agreement with, some of which are significant.

These concerns will be raised in future TANK Group discussions with the aim of

resolving them.

TANK Group comment

As

a group of individuals representing a range of sectors, we appreciate the

opportunity to work together to manage our most precious resource – water. We

come from different backgrounds and represent different interests, but

collectively as the TANK Group we have the same goal:

“To enable present and future generations to gain

the greatest social, economic, recreational and cultural benefits from our

water resources within an environmentally sustainable framework.”

Most

of the things we value have a connection with water: the environment, economy,

our cultural identity and general health and wellbeing. To ensure that these

values continue to be supported we have to work together. The

collaborative process obliges us to listen carefully to one another, to learn

from what we hear, and to find ways of reconciling our interests.

We

recognise that the entire community’s interests are at stake and we owe

thanks to our networks who have entrusted us to provide a sound and strong

voice. We

will continue to seek their feedback to make sure that we are effectively and

appropriately representing their aspirations.

We

realise the importance of our task. The Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri region

is both the economic hub of Hawke’s Bay and the place where many of us choose

to live. Yet some

of our waterways are in a degraded state and the risk to our futures of water

shortages is very real – as the 2013 drought showed.

Not

only do we need water to live and prosper, but our waterways are essential to

our very existence. The proverb Ko au te awa ko te awa ko au / I am the

river and the river is me resonates with us all. Water is a taonga and

collectively we see ourselves as being entrusted to protect our waterways and

to use water efficiently to ensure that current and future generation’s aspirations

are met.

This

First Report summarises our work to date and includes some

important agreements we have come to. Over the last twelve months we have

learned a great deal about the complexities of water management and we have

enjoyed working together to unravel the complexities. We have embraced this

challenge and we look forward to continuing to working together to ensure our

water and waterways are protected – now and in the future.

Table 1. The TANK Collaborative Stakeholder Group

|

Aki Paipper

|

Ngāti

Hori ki Kohupātiki

|

|

Brett Gilmore

|

Hawke’s

Bay Forestry Group

|

|

Bruce Mackay

|

Heinz-Wattie’s

|

|

David Carlton

|

Department

of Conservation

|

|

Christine Scott

|

HBRC

Councillor

|

|

Dianne Vesty / Leon Stallard

|

Hawke’s

Bay Fruitgrowers’ Association

|

|

Hugh Ritchie

|

Federated

Farmers

|

|

Ivan Knauf

|

Dairy

sector

|

|

Jenny Mauger

|

Ngā

Kaitiaki ō te Awa a Ngaruroro

|

|

Jerf van Beek

|

Twyford

Irrigators Group

|

|

Johan Ehlers

|

Napier

City Council

|

|

John Cheyne

|

Te

Taiao Hawke’s Bay Environment Forum

|

|

Marei Apatu

|

Te

Taiwhenua o Heretaunga

|

|

Mark Clews

|

Hastings

District Council

|

|

Mike Glazebrook

|

Ngaruroro

Water Users Group

|

|

Mike Butcher

|

Pipfruit

New Zealand

|

|

Morry Black

|

Matahiwi

Marae

|

|

Joella Brown

|

Te

Roopu Kaitiaki ō te Wai Māori

|

|

Neil Eagles

|

Royal

Forest and Bird Protection Society (Napier)

|

|

Ngaio Tiuka

|

Ngāti

Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated

|

|

Nicholas Jones

|

Hawke’s

Bay District Health Board

|

|

Peter McIntosh / Tim Hopley

|

Fish

and Game Hawke's Bay

|

|

Peter Paku

|

Mana

Whenua Ruahapia

|

|

Peter Beaven

|

HBRC

Councillor

|

|

Phil Holden

|

Gimblett

Gravel Winegrowers

|

|

Scott Lawson

|

Hawke’s

Bay Vegetable Growers

|

|

Terry Wilson / Wayne Ormsby

|

Mana

Ahuriri Iwi Incorporated

|

|

Tim Sharp

|

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

|

|

Tom Belford

|

HBRC

Councillor

|

|

Vaughan Cooper

|

Royal

Forest and Bird Protection Society (Hastings)

|

|

Xan Harding

|

Hawke’s

Bay Winegrowers

|

The TANK Group acknowledges the contributions of Adele Whyte, Dale

Moffatt,

Eileen von Dadelszen, Murray Douglas, Neil Kirton and

Nikola Bass who were previous members of the group.

The Group also acknowledges the support provided by researchers in

the Values, Monitoring and Outcomes Programme: Jim Sinner (Cawthron Institute),

Suzie Greenhalgh (Landcare Research), Natasha Berkett (Cawthron Institute),

Nick Craddock-Henry (Landcare Research) and Richard Storey (National Institute

for Water and Atmospheric Research) and the facilitation of Robyn Wynne-Lewis

(Core Consulting).

Figure 1: TANK Group field trip, February 2013

Table of Contents

TANK

Group comment v

1. Executive

Summary. 1

TANK Group Interim

Agreements. 3

Regional Plan

Changes. 3

Tangata whenua and

Mana whenua. 3

Values. 4

Minimum flows. 4

Water allocation. 4

Groundwater. 4

Good irrigation

practices. 5

Municipal water use

efficiency – interim agreements. 5

Global consents and

water sharing. 5

Staged reductions. 5

Water storage. 6

Nutrient management. 6

Stock exclusion. 6

Stormwater. 7

Wetland management. 7

Estuarine

management. 7

Tūtaekuri 7

Ahuriri 8

Ngaruroro. 8

Karamū. 8

2. Introduction. 10

3. Context 13

Resource Management

Act. 13

National Policy

Statement on Freshwater Management. 13

National

Environmental Standard for Sources of Human Drinking Water. 14

Hawke's Bay Land

and Water Management Strategy. 14

Regional Resource

Management Plan (including Regional Policy Statement) 14

Regional Plan

Changes – interim agreement. 16

4. The

TANK Collaborative Stakeholder Group. 16

5. Tangata

whenua and Mana whenua. 18

Tangata whenua and

Mana whenua - TANK Group Interim Agreements. 19

6. The

TANK Group decision making process. 21

7. TANK

Group Values, Objectives, Performance Measures and Management Variables. 25

Values. 25

Values – interim

agreements. 27

Objectives. 27

Performance

measures. 27

Management Variables. 29

8. TANK

region-wide topics. 30

8.1. Minimum

flows. 31

Minimum flows –

interim agreements. 32

8.2. Water

allocation. 32

Water allocation –

interim agreements. 33

8.3. Groundwater

investigations. 33

Groundwater –

interim agreements. 36

8.4. Measures

for improving water use efficiency. 36

8.4.1. Municipal

water use efficiency. 36

Municipal water use

efficiency – interim agreements. 37

8.4.2. Good

irrigation practices. 37

Good irrigation

practices – interim agreements. 37

8.4.3. Global

consents and water sharing. 38

Global consents and

water sharing – interim agreements. 39

8.4.4. Staged

reductions. 39

Staged reductions –

interim agreements. 42

8.5. Water

storage. 42

Water storage –

interim agreements. 43

8.6. Nutrient

Management 43

Nutrient management

– interim agreements. 44

8.7. Stock

exclusion. 44

Stock exclusion –

interim agreements. 45

8.8. Stormwater

management 45

Stormwater –

interim agreements. 47

8.9. Wetland

management 47

Wetland management

– interim agreements. 48

8.10. Estuarine

management 49

Estuarine management

– interim agreements. 49

9. Catchment

specific topics. 49

9.1. Tūtaekuri 50

Water quality. 52

Water quantity. 52

Tūtaekuri –

interim agreements. 53

9.2. Ahuriri 53

Water quality. 54

Water quantity. 55

Ahuriri – interim

agreements. 56

9.3. Ngaruroro. 56

Water quality. 58

Water quantity. 59

Ngaruroro – interim

agreements. 60

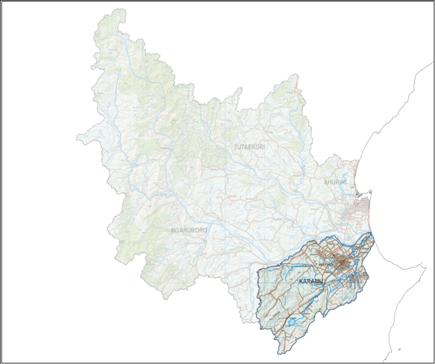

9.4. Karamū. 60

Water quality. 62

Water quantity. 63

Karamū –

interim agreements. 65

10. APPENDICES. 66

10.1. Management

Variables. 66

10.2. Glossary. 68

10.3. Key

documents and technical reports. 70

Coast and Estuaries. 70

Groundwater. 70

Hydrology. 71

Policy and Planning. 71

Tangata whenua and

Mana whenua. 71

Values. 72

Water Quality and

Ecology. 72

Tables and Figures

Table 1.

The TANK Collaborative Stakeholder Group. iv

Table 2:

Hypothetical example of the decision making process. 22

Table 3:

Hypothetical examples of the consequences of different Policy Options. 23

Table 4:

Values, Objectives and Performance Measures identified by the TANK Group's. 30

Figure

1: TANK Group field trip, February 2013. v

Figure

2: Plan Change Timeline. 2

Figure 3

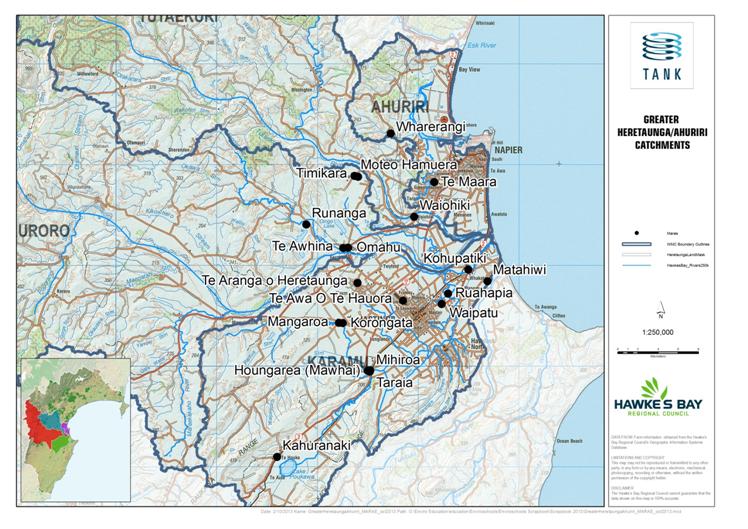

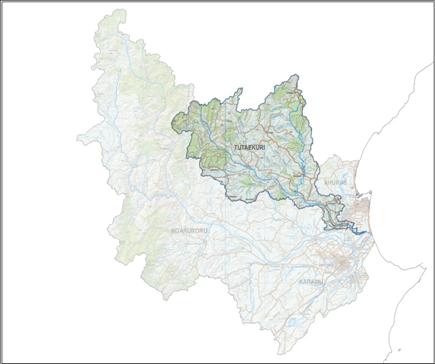

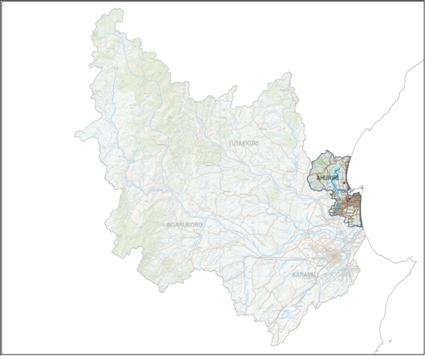

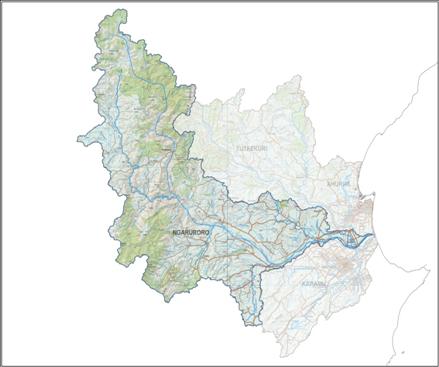

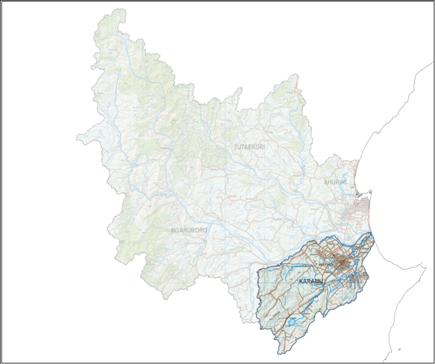

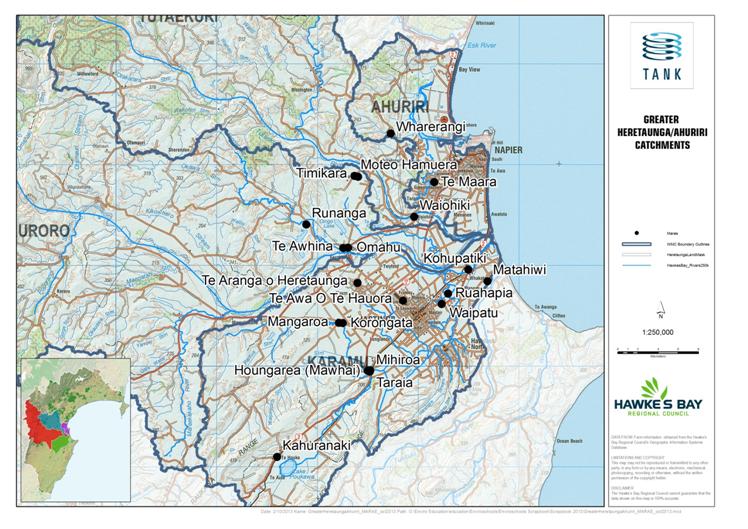

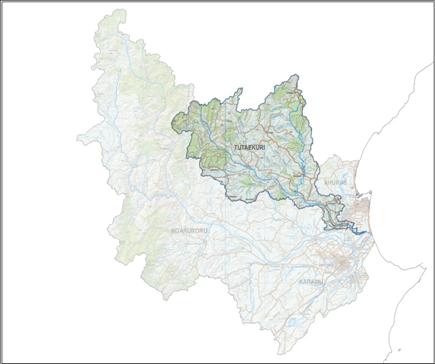

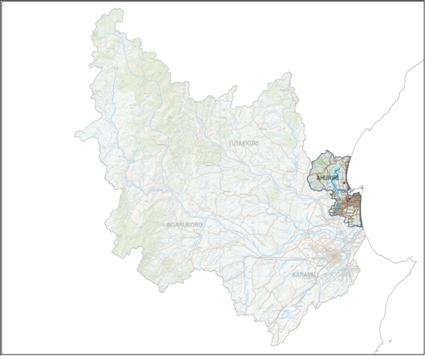

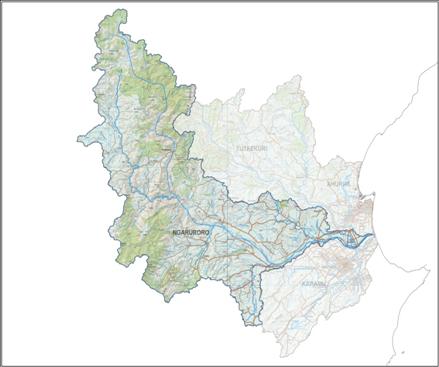

Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri Catchments. 12

Figure

4: Mike Glazebrook talking to the TANK Group at Te Tua Station; Field trip,

February 2013. 17

Figure

5: Marae locations. 20

Figure

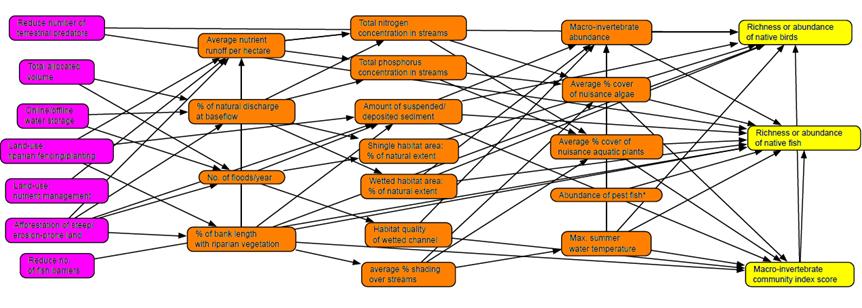

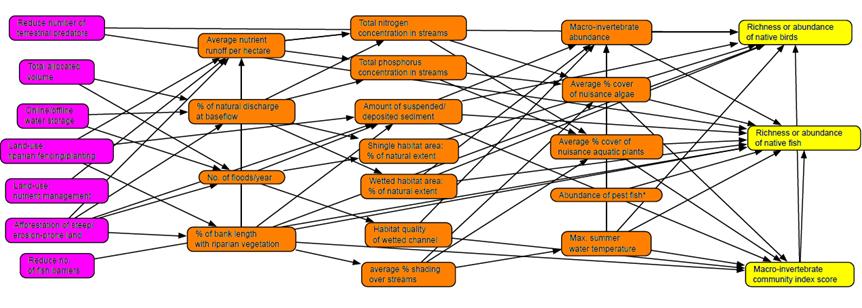

6: Developing an influence diagram.. 25

Figure 7:

Example of an influence diagram (NB: this is not a complete influence diagram) 26

Figure

8: TANK Group discussions, October 2013. 27

Figure

9: Field trip to the Ngaruroro River, February 2013. 32

Figure

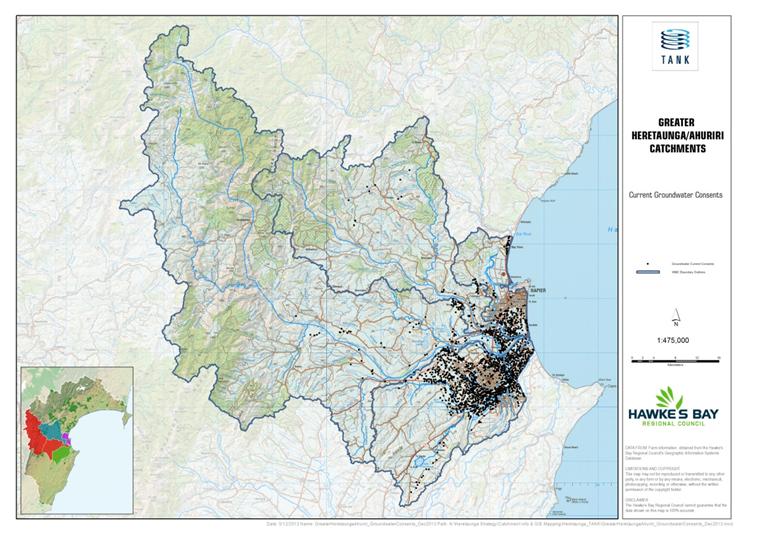

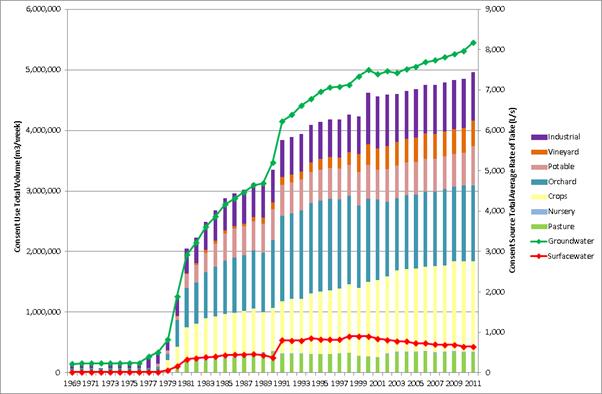

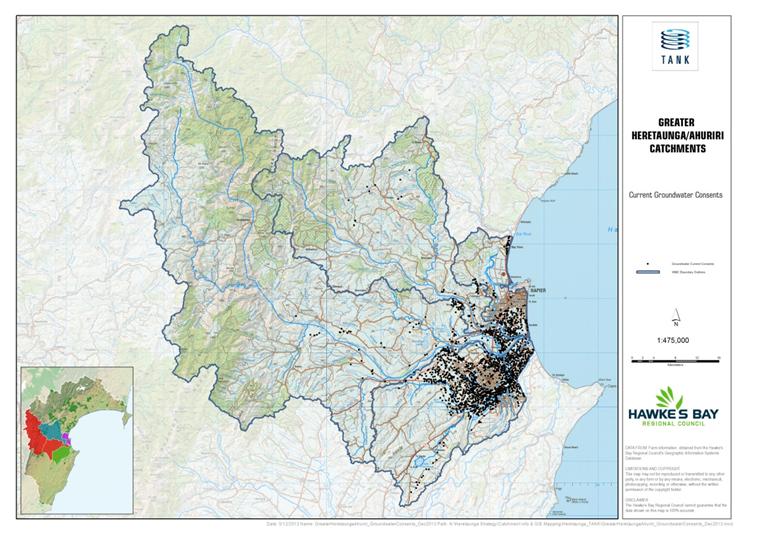

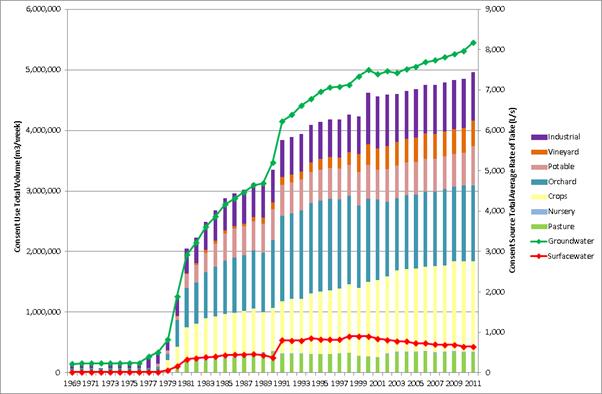

10: Groundwater takes in Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri 36

Figure

11: Good irrigation practices are a necessity in gravel-dominated soils like

the Gimblett Gravels; Field trip, February 2013. 40

Figure

12: Theoretical staged reduction regime. 43

Figure

13: The TANK Group supports the preservation of Wetlands. 50

Figure

14: Marei Apatu describing mana whenua connections with the Ngaruroro River;

Field trip, February 2013. 60

Figure

15: Aki Paipper discussing improvement measures being undertaken at Kohupātiki;

Field trip, February 2013. 63

Figure

16: Consented water takes in the Karamū catchment 66

Abbreviations used in this report

RMA Resource

Management Act 1991

NPSFM National

Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2011

LAWF Land

and Water Forum

HBRC Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council

RRMP Regional

Resource Management Plan

RPS Regional

Policy Statement

LAWMS Land

and Water Management Strategy

TANK Tūtaekuri,

Ahuriri, Ngaruroro, and Karamū catchments, or collectively the Greater

Heretaunga and Ahuriri area

TANK Group The

Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri (TANK) Collaborative Stakeholder Group

1. Executive Summary

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council (HBRC) is undertaking a change to the Regional Resource

Management Plan (RRMP) with respect to water management for the Tūtaekuri, Ahuriri, Ngaruroro

and Karamū catchments. The Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri Plan

Change will seek to implement the Hawke’s Bay Land and Water Management

Strategy and the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management and will

address specific water allocation and water quality issues in the four

catchments, including for wetlands and estuaries.

Council is

working with a collaborative stakeholder group to determine how these water

bodies should be managed. The TANK Group (named after the four catchments)

comprises 30 Hawke’s Bay representatives from agricultural and

horticultural sectors, tangata whenua, environmental and community interest

groups, and government agencies. HBRC has given a good faith commitment

to support any consensus recommendations from the TANK Group and to ensure the

Plan Change is consistent with the Group’s recommendations.

The key

aspects of the Plan Change that the TANK Group is tasked with making

recommendations to Council on are:

· Flow regime,

including low flow restrictions on takes

· Water allocation

(including for municipal and domestic supply)

· Security of water

supply for water users

· Policies, rules on

groundwater /surface water connectivity

· Surface water and

groundwater quality limits

· Tangata whenua involvement

in freshwater decision making

· Use of

Mātauranga Māori in monitoring and reporting

· Wahi tapu register

· Policies, rules and

incentives on:

o riparian management

& stock exclusion

o water storage

o water efficiency

o water

sharing/transfer

o nutrient

loss/allocation

o good irrigation

practices

o stormwater

management

o other agricultural

practices

This report

summarises the

TANK Group’s work

between October 2012 and December 2013 and includes the Group’s provisional

agreements listed below. The timeline for the Plan Change is outlined in Figure

2.

Figure 2: Plan Change Timeline

TANK Group Interim Agreements

The following

Interim Agreements are supported ‘in principle’ by the TANK Group and most of

their wider networks.[1]

The Interim Agreements provide a platform for the TANK Group to proceed with

further discussions and problem solving. For background and context around

these agreements please refer to the detail in the body of the report. Many of

the agreements are related to ‘next steps’ – and will be further developed by

the group through 2014 and beyond as technical information becomes available

and the Plan Change is drafted.

Regional Plan

Changes

1. The TANK

Group will review the Tukituki Plan Change once it is completed and consider whether

to use the same approaches where the same issues arise in the Greater

Heretaunga and Ahuriri Plan Change so that, where appropriate, the RRMP is

consistent across catchments.

Tangata whenua

and Mana whenua

2. The

TANK Group recognises the following:

a. That

the relationship between tangata whenua and freshwater is longstanding and

fundamental to their culture

b. That

water is valued by tangata whenua as a taonga of paramount importance

c. That

kaitiaki have obligations to protect and enhance the mauri of water and the

associated environment

d. That

tangata whenua have an obligation to be involved in freshwater decision-making

e. That

the relationship between tangata whenua and mana whenua and their wāhi

tapu, wāhi taonga and other taonga must be protected.

f. Ngāti Kahungunu whānau, hapū and

iwi have rights and interests in freshwater that extend beyond the “cultural”

space. While this has been discussed, exactly how this might manifest remains

uncertain.[2]

Values

3. The

TANK group will use the values identified in each of the catchments to assess

the consequences of policy options and seek to identify options that provide

for each of these values.

4. The

TANK group will recognise spatial variation of catchments and their values in

the limit-setting process, by setting objectives and limits for sites and

reaches within catchments where appropriate.

Minimum flows

5. Minimum

flow setting needs to take into account the impacts on environmental, cultural,

social and economic values using a variety of methodologies (e.g.

Mātauranga Māori; economic models).

6. The

TANK Group supports the use of RHYHABSIM for minimum flow setting where

appropriate, to assess the implications of different flow regimes on the level

of habitat retention for agreed species.

Water allocation

7. The

TANK Group recognises that the RRMP needs to give effect to the NPSFM by

ensuring that water is not over-allocated.

8. The

TANK Group believes that alternative methods for determining total water

allocation limits should be explored as a possible substitute for a simple sum

of all authorised abstractions.

9. The

TANK Group considers that monthly, rather than weekly, allocation volumes for

water take consents are appropriate (as well as a ‘rate’ of take).

Groundwater

10. The

RRMP needs to be informed by a better understanding of the groundwater

resources so that limits can be set. The TANK Group supports ongoing HBRC

groundwater investigations and considers that these investigations should

include:

a. Water

balance (How much water can sustainably be abstracted?)

b. Aquifer

recharge from surface water

c. Relationship

with surface water (stream connectivity, depletion effects and ecology)

d. Areas

of concern (quantity and quality)

e. Specific

detailed investigations into the effects of individual takes in the unconfined

and semi-confined areas of the Heretaunga aquifer

f. Nutrient

and contaminant pathways

g. The

significance of stygofauna

11. The

TANK Group believes that supplementation of surface water flows from the

confined aquifer should be explored.

Good irrigation

practices

12. The

TANK Group considers that all water consent holders should be required to

provide evidence to HBRC (at a frequency to be determined) that they are

compliant with industry IGP irrigation practices.

Municipal water

use efficiency – interim agreements

13. The

TANK Group considers that municipal water suppliers should have demand

management and conservation strategies.

14.

The TANK Group believes that some restrictions on urban and permitted domestic

water supplies are appropriate in certain circumstances, such as when other

abstractors from the same or connected resources are experiencing significant

water restrictions and/or bans.

Global consents

and water sharing

15. The

TANK Group encourages HBRC to continue to work with water user groups to assist

with setting up global consents.

16. The

TANK Group would like to see a process for instantaneous transfers of water

consents[3]

and will aim to identify the circumstances where this would be appropriate.

Staged reductions

17. The

TANK Group considers that HBRC should investigate the benefits of staged

reductions of water abstraction in the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri region.

For staged reductions:

a. A

global consent for a surface water zone would be preferable

b. Incentives

will be needed to participate in a staged reduction policy (e.g. lower minimum

flow restrictions)

c. Telemetry

will be required for all water users participating in a staged reduction

policy.

Water storage

18. The

TANK Group believes farming practices which maximise water retention in the

landscape is likely to reduce irrigation demand and hence reduce the need for

large scale water storage in the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri region.

19. To

maintain current levels of food and fibre production, the TANK Group considers

that water storage will be required if allocations are reduced and/or minimum

flows are increased.

20. The

TANK Group encourages HBRC to make allocations at high flows more easily

available on-farm and/or community storage and distribution[4] through the

consenting process.

Nutrient

management

21. The

TANK Group agrees that nutrient management is necessary to help maintain

life-supporting capacity, avoid proliferations of undesirable algal growths,

avoid toxicity to aquatic species and protect drinking water supplies.

22. The

TANK Group believes that all farmers should be required to provide evidence to

HBRC that they are compliant with industry IGP nutrient management practices.

23. The

TANK Group considers that policy and management measures should target

“hot-spot” areas where the values identified by the TANK Group are being

compromised or at risk of being compromised by excessive nutrients. These areas

need to be identified as well as the critical source areas for nutrients.

24. The

TANK Group agrees that farm environmental management plans, which may go beyond

IGP, should be mandatory for all landowners in “hot-spot” areas.

25. The

TANK group recommends that monitoring of ground water nutrients take into

account appropriate temporal lags between nutrient management practice and

measured nutrient concentrations in ground water samples

Stock exclusion

26. The

TANK Group supports exclusion of cattle from waterways in the Greater

Heretaunga and Ahuriri region.

27. In

catchments where stock (other than cattle) in streams is proven to be a

problem, wider stock exclusion should be considered.

Stormwater

28. The

TANK Group recommends the re-establishment of the Regional Stormwater Working

Group (with possible inclusion of some TANK members) to review and where

necessary update the Regional Stormwater Strategy.

29. The

relevant agencies involved in stormwater management should investigate options

including:

a. Controls

on zinc roofing e.g. require all new roofing to be painted

b. Bylaws

on design, operation and management of industrial sites

c. Education

and knowledge transfer

d. New

developments to be required to include sustainability attributes e.g. Low

Impact Urban Design and Development

e. Joining

up networks with historical problems

Wetland

management

30. The

TANK Group recognises the importance of wetlands in the Greater Heretaunga and

Ahuriri region and believes that measures should be undertaken to support the

preservation of remaining wetlands, consistent with other policy documents such

as the Regional Policy Statement and the NPSFM.

31. The

TANK Group considers that wetlands should be identified and categorised to

determine ecological significance and that wetlands deemed ecologically

significant should be given protection that is consistent with the NPSFM.

Estuarine

management

32. The

TANK Group believes that the estuaries in the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri

region should be managed so that popular activities including swimming and food

gathering are able to be safely undertaken during normal climatic conditions

(i.e. outside periods of high rainfall when bacteria concentrations are

naturally high). Some areas may require improvements over an extended timeframe

to meet community aspirations.

Tūtaekuri

33. The

TANK Group is concerned about the excessive periphyton growth in the lower

Tūtaekuri and requests that HBRC investigate and report back to the Group

on causes of these growths and possible measures to reduce them.

34. The

TANK group will consider whether to recommend confirming or amending the

existing minimum flow and allocation.

Ahuriri

35. The

TANK Group considers the Ahuriri Estuary to be a site of ecological, cultural

and recreational significance and recommends that all reasonable measures are

undertaken to support these uses and values including restoring suitability for

food gathering. .

36. The

TANK Group is concerned about sediment, nutrient, bacteria and contaminant

inputs to the Ahuriri Estuary and requests that HBRC investigate and report back

to the Group on sources of these and possible measures to reduce them.

37. The

TANK Group is concerned about poor water quality in the urban streams and

requests that HBRC investigate and report back to the Group on causes of the

poor water quality and possible measures to improve it.

Ngaruroro

38. The

TANK Group considers that management of the Ngaruroro catchment may be able to

be based around four zones: upstream of Whanawhana; Whanawhana to Fernhill;

Fernhill to the coast; and the Waitangi estuary.

39. Further

monitoring and investigations are recommended to better identify the sources of

water clarity degradation and nutrients in the Ngaruroro catchment.

40. Improved

understanding of groundwater and surface water linkages and stream depletion effects

is needed before adjustments to the existing flow regime can be agreed.

41. The

main minimum flow on the Ngaruroro River (2400 l/s at Fernhill) should be

reviewed and assessed for how well it is providing for in-stream values

including ecological, recreational and cultural values.

42. Any

changes to minimum flow and groundwater / surface water linkage rules need to

consider impacts, especially security of supply and economic impacts, on water

abstractors including irrigators and processors.

Karamū

43. The

TANK Group is concerned about poor water quality, sediment, excessive

macrophytes and lack of riparian vegetation in the Karamū system and its

effects on cultural, ecological and recreational values including food

gathering. The Group requests that HBRC investigate and report back to the

Group on causes of the poor water quality and possible measures to improve it.

44. Improved

understanding of groundwater and surface water linkages and stream depletion

effects is needed before adjustments to the existing flow regime can be agreed.

45. Any

changes to minimum flow and groundwater / surface water linkage rules need to

consider impacts, especially security of supply and economic impacts, on water

abstractors including irrigators and processors.

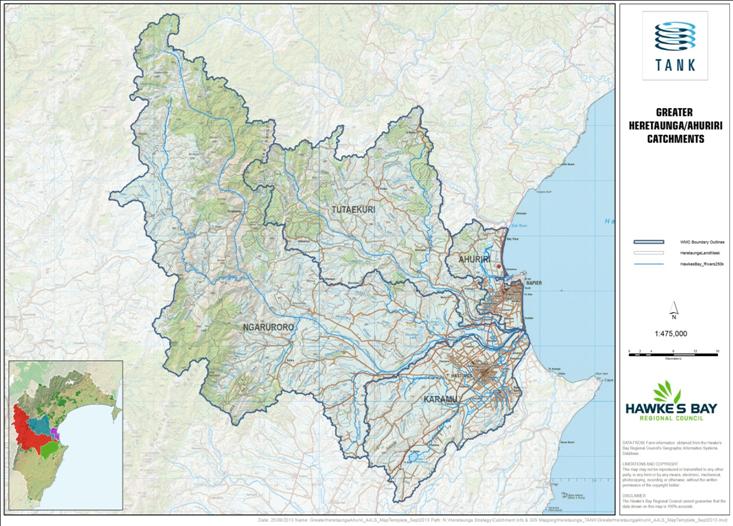

2. Introduction

Hawke’s

Bay Regional Council (HBRC) is undertaking a change to the Regional Resource

Management Plan (RRMP) with respect to water management for the Greater Heretaunga and Ahuriri

region in Hawke’s Bay. The area under review is the water catchments

of Tūtaekuri,

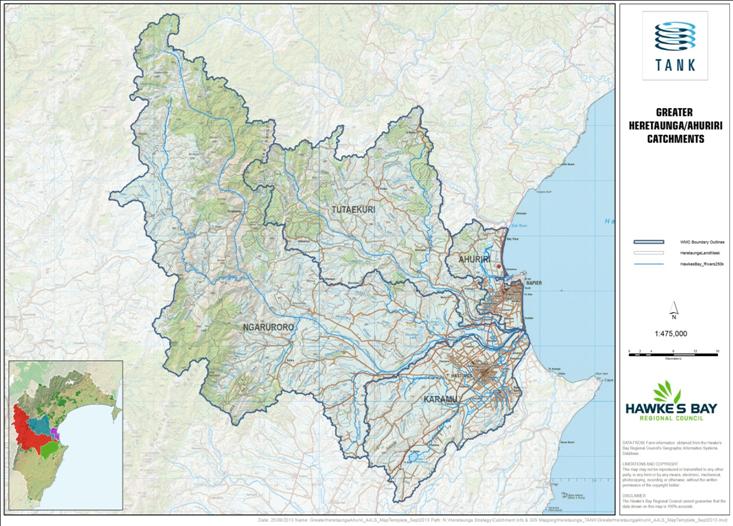

Ahuriri, Ngaruroro and Karamū (Figure 1) and includes the Heretaunga Plains, the major urban centres

of Napier, Hastings and Havelock North and the estuarine and coastal receiving

environments.

The

Greater

Heretaunga and Ahuriri Plan Change will seek to implement the

Hawke’s Bay Land and Water Management Strategy and the National Policy

Statement for Freshwater Management and will address specific water allocation

and water quality issues in the catchment.

The Greater Heretaunga and

Ahuriri region

is large and diverse, and the water related issues complex. Because of this

complexity, the Council has asked a group of Hawke’s Bay residents to make

recommendations on how these water bodies should be managed. The TANK

Collaborative Stakeholder Group (named after the four catchments) comprises 30

Hawke’s Bay representatives from agricultural and horticultural

sectors, tangata whenua, environmental and community interest groups, and

government agencies.

The

TANK Group has held 11 full day meetings plus other small group meetings and

workshops over the past 14 months to discuss the issues and to seek sustainable solutions to

the region’s freshwater challenges. HBRC has given a good faith commitment

to support any consensus recommendations from the TANK Group and to ensure the

Plan Change is consistent with the Group’s recommendations.

This

report summarises the work of the TANK Group to date. The report documents a

number of provisional agreements. These include statements of values,

objectives and some performance measures. The merits of current and alternative

policy options (for influencing outcomes) have also been discussed at length.

Without having comprehensively tested the consequences of adopting various